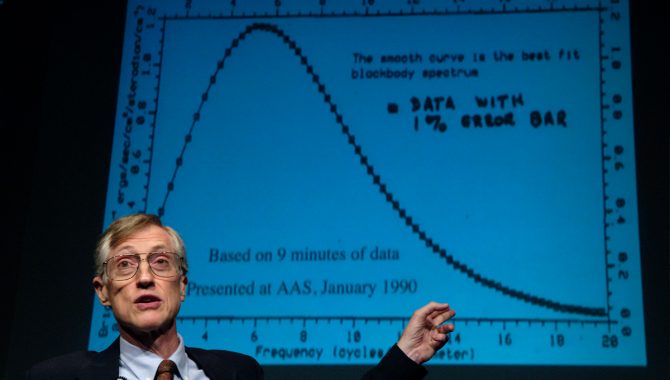

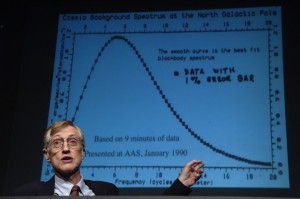

NASA scientist Dr. John C. Mather shows some of the earliest data from the NASA Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) spacecraft during a press conference held on Oct. 6, 2006, at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC. Dr. Mather shares the 2006 Nobel Prize for Physics with George F. Smoot of the University of California for their collaborative work on understanding the Big Bang.

Photo Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls

Every successful Principal Investigator-led team stands on the shoulders of giants.

NASA scientist Dr. John C. Mather shows some of the earliest data from the NASA Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) spacecraft during a press conference held on Oct. 6, 2006, at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC. Dr. Mather shares the 2006 Nobel Prize for Physics with George F. Smoot of the University of California for their collaborative work on understanding the Big Bang.

Photo Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls

NASA’s success depends on how well it develops, acquires, and uses knowledge. The NASA Academy of Program/Project & Engineering Leadership (APPEL) has hosted a series of training events called Principal Investigator (PI) Team Masters Forums in collaboration with NASA’s Science Mission Directorate and NASA’s Science Office for Mission Assessments to meet a unique set of learning needs NASA PI-led mission teams.

PI-led missions are collaborations among NASA centers and university, industry, and international partners. They are selected through NASA’s announcement of opportunity (AO) process from the Explorers, New Frontiers, or Discovery programs, which provide flight opportunities for small, focused, scientific investigations through limited resources and short development times. Past missions from these programs include Near-Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR), Mars Pathfinder, Kepler, the Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer (FUSE), Swift, the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR), New Horizons, and Juno.

While many PI-led teams apply for the chance to fly their science investigations through programs, only a few are selected. Teams are subjected to a rigorous multi-step review process to ensure that the missions they are proposing is technically feasible, scientifically relevant, and can reliably meet the cost and schedule demands set by the program. Because the process is so competitive and mission success is critical, participation in NASA’s PI Team Masters Forums is part of SMDs Policy Directive 13B (SPD 13B) and is required for all announcement of opportunity Phase A selections.

With a strong belief in the power and purpose of storytelling, the purpose of NASA’s PI Team Masters Forums was to enable these PI-led teams to engage, share with, and learn from fellow practitioners from a broad range of science missions through their stories, shared experiences, and lessons learned as they embark upon making their mission a success.

In order for the valuable knowledge and lessons of these forums to extend beyond the walls of the room in which they were originally delivered, this will be the first installment of a series of short articles on some of the critical knowledge and management essentials captured during these training events.

The Role of the Principal Investigator on a PI-Led Team

The Principal Investigator (PI) is the centerpiece for any PI-led team. He or she conceives an investigation and is responsible for carrying it out—developing scientific objectives and an instrument payload—and reporting its results.

Inherent to the challenge of conceiving of what needs to be measured is determining the engineering possibilities that exist to achieve it. John Mather, PI for the Far IR Absolute Spectrophotometer (FIRAS) instrument on the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE), once said that one job of the PI is to “translate the general [scientific] desire into particular, specific numerical things like how big is the aperture? How sensitive are the detectors? What exact wavelengths are we going to use? How does that match up to the technology we can get? The PI has a lot of responsibility and authority in this area.”

This was certainly true for Kepler PI Bill Bouruki, whose team spent nearly two decades revising, testing, publishing, and proposing their mission to explore exoplanets before NASA finally accepted them as a Discovery mission in 2001.

The PI is also responsible for assembling and leading the right talent and expertise to get the job done. The PI is central to a project’s communication network, interfacing with team members including the program executive, mission manager, program scientist, project scientist, executive advisory council, science team, education and public outreach officer, project manager, systems engineer, and safety and mission assurance manager. Success hinges on how well the PI manages these relationships.

For every mission, Pat McCormick, former PI on the Stratospheric Aerosol and Gas Experiment (SAGE), would invite the whole team—secretaries, engineers, budget analysts, technicians, everyone—to an after-hours gathering where he’d talk about the mission: its purpose, challenges, and significance. It was important to McCormick that the whole team knew who he was and understood what they were building. More importantly, he thought each member of the team should be equipped to talk about the mission with people ranging from their colleagues at the office to their next-door neighbors.

“You’re the leader of the team. You’re the team organizer. You’re the team builder. You’ve got to get that whole team put together. Do not isolate yourself,” said McCormick. “You’ve got to be home to make the decisions and you’ve got to be that one person that feels that total responsibility to make the mission succeed.”

Time and again, the relationship between the principal investigator and project manager is given particular attention. The project will change on a daily, if not hourly, basis. Information and updates constantly come from everywhere and the PI and PM need to be on the same page.

This communication was critical for the COBE mission. Initially designed to fly on a Delta rocket, COBE was reassigned as a shuttle payload set to launch in 1988 as a result of a policy change. In 1986, the Challenger accident altered their plans once more. COBE eventually launched aboard a Delta rocket in 1989.

COBE Project Manager Dennis McCarthy once noted that he and John Mather would meet regularly. “John and I would meet every week in my office with the door shut to have lunch. We would discuss the program. We would discuss the people. It was just communication,” McCarthy said.

“For me it was a real important part of the building of trust,” said Mather. “If the investigators aren’t sure that the management is on their side, then they go nuts. But I sort of knew when…I had a concern or an issue that [Dennis] would grin at me and twinkle his eyes, and I would say, OK, he’s going to take care of it. It’s going to be OK. And it was. This happened enough that I could say, OK scientists, I know you’re worried about this, but project management understands what the problem is and they are on our side.”

Attitude is another important element a PI must be aware of, Mather mentioned. “If controls, in a way that you may not know, what people do,” said Mather. “We can make some really stupid mistakes if we just don’t have the right attitude.”

The PI is also responsible for assuring that all cost, schedule, and performance objectives set by the program are met. Tools such as Earned Value Management and Joint Confidence Levels are useful for tracking planned versus actual expenses and milestones and managing the expectations of project stakeholders.

For McCormick, he would look at the planned versus actual for every level of the work breakdown structure. “I find that if you do this at every work breakdown structure level—every level of the project, everything you’re buying or building—if you look at planned versus actual, you will really be on top of what’s going on,” he said. “You will smell the rat quickly and know you have a problem. This is exceedingly important.”

Ultimately, the words of the Swift mission PI Neil Gehrels ring true for all mission principal investigators: “The responsibility [of the mission] begins and ends with you.”