May 29, 2009 Vol. 2, Issue 5

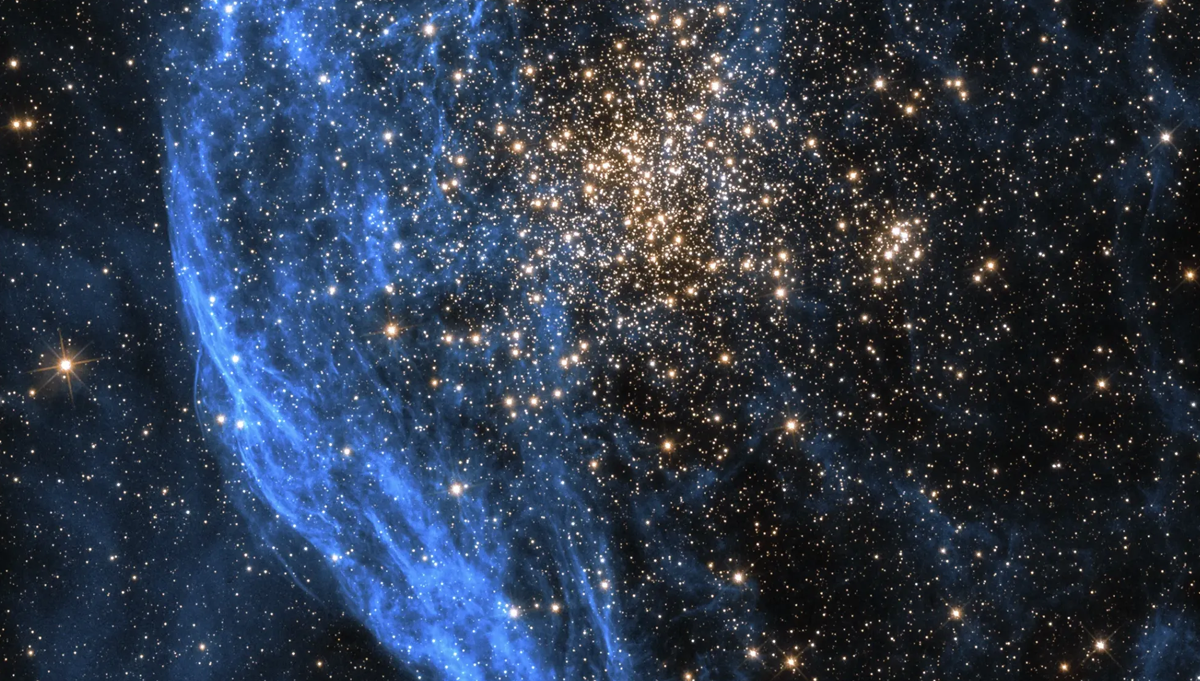

With the conclusion of the remarkable final servicing mission of the Hubble Space Telescope, it is worth pausing to reflect on what Hubble has meant for space exploration since its launch in 1990.

No other single space mission has contributed so much to our knowledge about the solar system and beyond. It has helped us determine the age of the universe with much greater accuracy than ever before; learn how planets are formed; observe distant galaxies in all stages of formation; uncover evidence of dark energy; and detect the first organic molecule discovered on a planet outside our solar system. Astronomers using its data have published over 7,000 scientific papers.

The success of the Hubble does not rest solely with NASA. It extends even beyond our partnerships with the European Space Agency, with industry, and with the scientific community, all of which have been involved at every step of the way. Hubble stands as a reminder that grand challenges belong to society. Like any endeavor of this magnitude, Hubble demanded a far-reaching vision of what could be achieved, a commitment to make that vision a reality, and a determination to persevere in the face of setbacks that inevitably occurred along the way. And that determination ultimately rested with the public, the true owners of its success.

A grand challenge like Hubble requires such a large, long-term commitment that it can only come about when social, political, economic, and technological forces line up at the same time and create the right conditions for a bold undertaking that has the potential to transform the world as we know it. When we succeed, history has shown that society benefits and changes in unexpected ways.

Consider, for example, the construction of the transcontinental railroad in the 1860s. It made the world smaller. Conceptions of speed and time changed forever. People, ideas, and information could travel distances in days that previously took weeks. Time zones had to be established across the country. There were new national markets for goods and materials.

The most dramatic grand challenge of the twentieth century — to land a man on the moon and return him safely to Earth before the end of the 1960s — showed us that humans could break the chains of gravity, fly beyond Earth’s orbit, and explore space as we had once explored oceans and continents. In his speech at Rice University in 1962, President Kennedy made clear that he understood what getting to the moon would require: “…that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills.”

We had to come up with new ways of organizing to undertake complex projects. The disciplines of project management and systems engineering matured in the Apollo era because the grand challenge of sending humans to the moon and back demanded new levels of technical and managerial excellence.

The same was true for the Hubble Space Telescope — we had to come up with new ways of doing things. There had never been a large-scale space telescope, though the great astrophysicist Lyman Spitzer’s vision for it predated the Space Age by a decade. There had never been a need for an optical system in space as perfect as Hubble’s. New processes had to be invented to manufacture the mirrors for the telescope, with no margin for error.

The technology Hubble demanded was so complex that visionary leaders and inventors came up with a modular design that would be serviceable by astronauts aboard the Space Shuttle. When problems with the original mirror on the telescope became apparent shortly after launch in 1990, this design made it possible to fix Hubble with the first servicing mission. Since then, that design enabled us to upgrade and improve the telescope with new technology on subsequent servicing missions. Hubble’s new lease on life is the direct result of that far-sighted decision more than thirty years ago to build a telescope that could be serviced on orbit.

The crewmembers of STS-125 who performed so commendably serve as a reminder that our investments in human spaceflight have been critical to Hubble’s success. Human spaceflight and robotic missions like Hubble are two sides of the same coin — both are essential to our efforts to explore, to increase our knowledge and understanding of the universe.

This story of exploration has been one of collaboration from the beginning — with our partners in the European Space Agency, in industry, in universities, and in the science community — and it has extended even to the policies that govern the uses of the telescope. The Hubble is open to all: any astronomer in the world can submit a proposal and request time on the telescope. The data collected by Hubble is eventually released to the entire scientific community, which has led to unanticipated discoveries and findings. This openness has become a model for sharing scientific data and information.

None of the benefits of Hubble would have been possible without the sustained support of the public. When the question of funding this final servicing mission came up a few years ago, the public raised its voice loudly and clearly in favor of extending its life. The Hubble has come to occupy a special place in the public imagination. There have even been exhibitions in museums that have showcased its images as works of art. Like all our greatest successes in spaceflight, which have resulted from difficult choices among competing priorities for scarce resources, Hubble truly belongs to the people.

Shortly after completing the first-ever spaceflight by an American astronaut, John Glenn said, “Exploration and the pursuit of knowledge have always paid dividends in the long run — usually far greater than anything expected at the outset.” His observation certainly applies to the Hubble Space Telescope. This final servicing mission was one last investment in the long run. If history is any indication, we can expect that the dividends of exploration will once again far exceed our expectations.