By Laurence Prusak

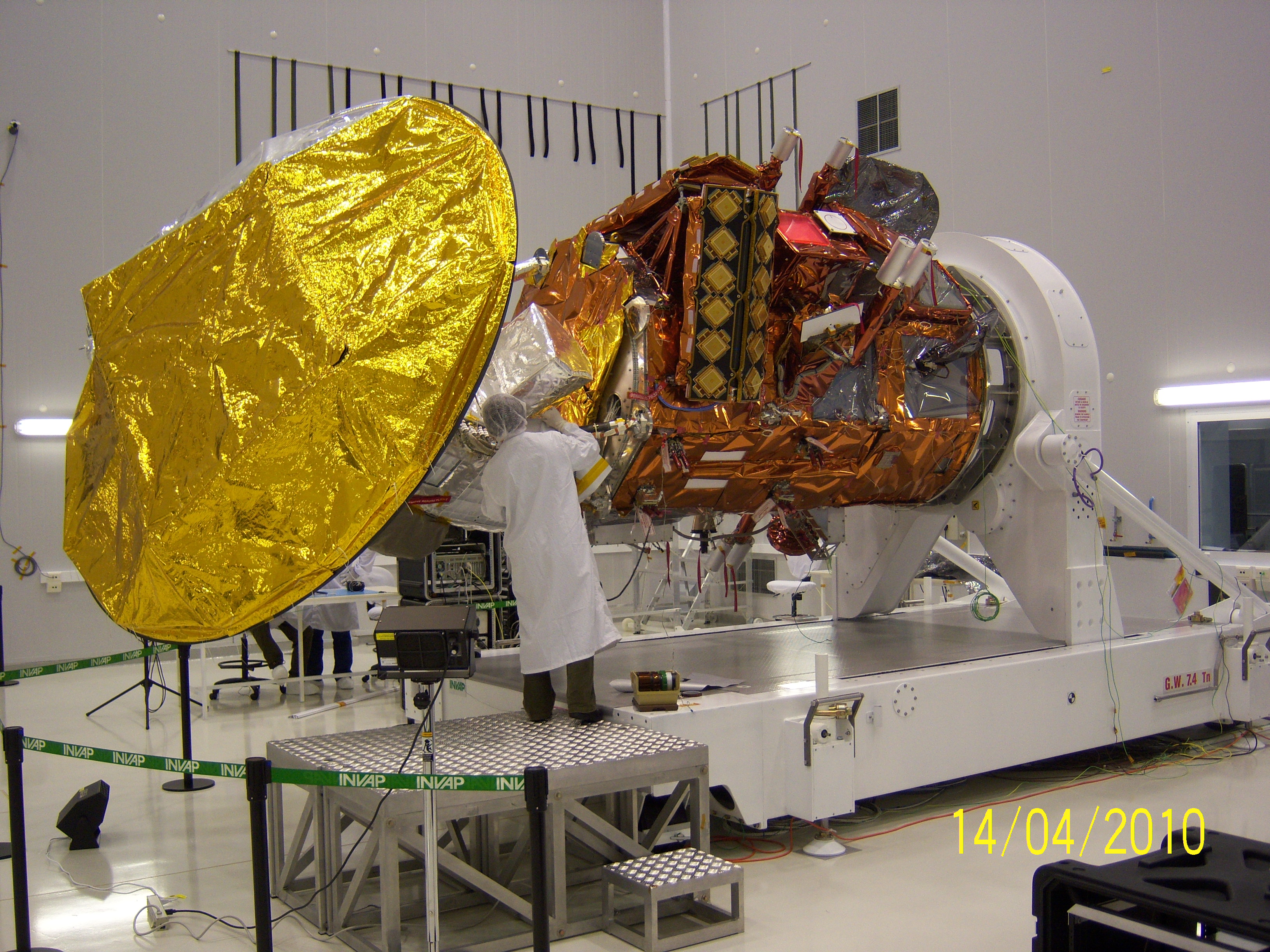

At the end of February, the Office of the Chief Engineer at NASA convened a meeting at Kennedy Space Center to discuss a variety of practices and policy issues regarding knowledge management at the agency. The meeting included representatives from NASA centers and some guests who talked about knowledge management work being done at the FBI and the World Bank. For two and a half days, we shared experiences and thoughts about how best to share and use knowledge at NASA.

One aspect of the meeting stood out for me, however. While we were all there to talk about knowledge, the word itself clearly had diverse meanings for the assembled practitioners. In fact, if we had gone around the room asking people what knowledge is, there would be far less overlap in meanings than anyone would have guessed going into the meeting.

That fundamental disparity has been my experience in many such meetings for the past two decades or so. Unlike our shared understanding of almost any other term used in organizations—technology, systems, information, data, markets, processes—we seem to lack a common idea of what knowledge is. This makes working with knowledge quite problematic.

Whenever I mention that I study and consult on the subject of knowledge, this absence of shared understanding of the meaning of the word “knowledge” is conveyed to me in starkest terms. Some people ask me if I can help them fix their PC (absolutely not); others want to know if I can help their kids write a philosophy term paper (I probably could, but I’m not a philosopher); one person asked me to explain the Myers-Briggs personality test (my explanation would be no better than most people’s). When a large, diverse organization undertakes to develop some innovative knowledge practices, think of the semantic confusion that is likely to ensue—and get in the way of effective cooperative work.

Part of the problem is a linguistic issue. We really have just one word—knowledge—for what is in fact a very broad set of meanings or understandings. Many other languages have at least two words for knowledge; some Asian languages have three. The classical Greeks had at least seven words they used to describe different varieties or aspects of what we are forced to call “knowledge.”

Let me give you an example of how wide are the parameters of what we think of as knowledge. On one end of a continuum of meanings of “knowledge,” we might have the example of the Pythagorean theorem beloved (or hated) by high-school geometry students. It can easily be considered as a “piece” of knowledge. It surely is a part of the whole we call geometrical knowledge. The Pythagorean theorem is complete in itself. It needs no context or further documentation to make its meaning clear. It can be readily and fully explained by a geometry teacher and understood by her students.

Unlike our shared understanding of almost any other term used in organizations—technology, systems, information, data, markets, processes—we seem to lack a common idea of what knowledge is. This makes working with knowledge quite problematic.

Now let’s move to the other end of the spectrum of meanings of “knowledge.” A few months ago, I gave a talk to a group of Irish executives visiting Boston. When I was discussing knowledge and knowledge management, one of them told us that his brother was a well-known horse trainer in rural Ireland. The brother was famous for his skills but practically inarticulate when it came to describing how he does what he does. Even though a clear explanation of his work might bring him added and meaningless way. And this is a person in a country where people are known for their expressive skills! But his knowledge is almost all tacit—subtle, contextual, and very hard to represent or make understandable except, perhaps, by showing rather than telling. Yet we would likely use the same English word to describe the Pythagorean theorem and the expertise of the horse trainer. How can one devise acceptable practices and policies for knowledge when the word can mean such different things?

Well, some organizations do it. How they do it is by devising a consensus definition that meets the needs of the organization and is clear to everyone in the organization. Its that simple. No language police are called for, no attacking others meanings and pet ideas—just a negotiated truce that makes clear what we are talking about when we talk about knowledge.

More Articles by Laurence Prusak

- The Knowledge Notebook—Network Success (ASK 45)

- The Knowledge Notebook—Indicators (ASK 44)

- The Knowledge Notebook—The Burden of Knowledge (ASK 43)

- The Knowledge NotebookThe Meaning of Meaning (ASK 42)

- The Knowledge NotebookThe Limits of Knowledge (ASK 41)

- View More Articles