Vol. 6, Issue 1

The NASA History Offices latest publication captures the thinking of NASA senior leadership on the agencys 50th anniversary.

Beginning in 2007, the NASA History Office began interviewing NASA senior leaders about their reflections on their experiences and their thoughts on the future of the agency. The resulting publication, NASA at 50: Interviews with NASA Senior Leadership, features interviews with NASA leaders between 2007 and 2008 including Bill Gerstenmaier, Rex Geveden, Mike Griffin, Lesa Roe, Christopher Scolese, and Ed Weiler.

The following is an excerpt on learning from the past from an interview with former Chief of Safety and Mission Assurance Bryan O’Connor. [Hyperlinks were added by ASK the Academy.]

What do you believe are the lessons learned through the last 50 years?

In the job I’m in, I tend to focus on lessons learned that had to do with failures and how we recovered from them. That’s part of the nature of this job. I sometimes refer people in my community, and in the engineering com- munity, to a book by a fellow named [Henry] Petroski called To Engineer Is Human. In that book, his basic premise is that all the great engineering advances throughout history tended to come from recovering well from failures. Not to say that every time there was a failure, people recovered well from it. Sometimes people ignored failures, and so they didn’t get any learning from them. But when you have a failure, you owe it to yourself, the people who may have suffered in the failure, and the future, to learn as much as you can about why it happened and how to avoid it in the future.

So I tend to look at things like the Apollo fire, the failures weve had in our spaceflight such as the Atlas failure with lightning back in 198720 years ago this month, in factthe human spaceflight failures that weve had, failures in operations where we lost people in aircraft, and some of the mission failures weve had in our robotics programs, and I worry that we will lose some of those lessons. I worry a little bit about how we capture lessons learned. We have a lot to do there to make sure we dont lose those.

This office several years ago, before I got here, developed a system called Lessons Learned Information System, LLIS. As you know, every two or three years any kind of database or computer program software you come up with to do anything is pretty much outmoded, and its the same with the LLIS. It was a great thing to do. It was meant to solve part of that problem on not losing our lessons learned. When you look at it today, you say, Weve got to do better than that. Its not searchable like wed like it to be. Its not using the latest technology and so on.

Im a believer in lessons learned not just being in a database or in a book somewhere, but also in the day-to-day operations, the procedures, the design requirements, the standards that we have. Those things need to capture our lessons learned. Thats how we would not lose them.

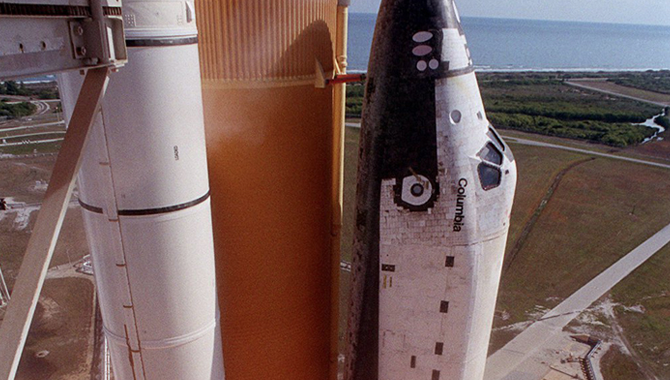

I mentioned the Atlas failure, struck by lightning. Well, that lesson had been learned in Apollo. Apollo 12 was struck by lightning. There was a lot of work in developing the science and understanding of triggered lightning, which is a phenomenon that shows up much more in launch vehicles with long ionized plumes coming out of them than it would in aircraft, where it’s not a big deal. But from the Apollo experience there was a lot of learning and lessons that came out of that, and yet a few years later, in 1987, we were struck by triggered lightning and lost the payload and the Atlas rocket.

Bryan OConnor, Chief of Safety and Mission Assurance, talks about lessons from AC-67.

In retrospect, you’d say we failed to learn that lesson. It turns out that when you go back and look at that accident investigation, you find that there was a rule in the rule book, the launch commit criteria, that dealt with that. It said, don’t launch in clouds that are a certain depth with the freezing layer going through them. But there was a lack of understanding by the launch team about why that was there, what it was for. It’s not clear from reading the transcripts that they even knew that that rule had anything to do with triggered lightning, because they were asking questions about icing and so on. So you could say that we had imperfect capture of lessons learned there, and that that was part of the root cause of that accident. That’s the kind of stuff I worry about.

How do we keep from repeating mistakes? Shame on us when we have something happen twice. It’s just almost unforgivable, and yet you really struggle with how to deal with it. There are so many lessons we’re learning every day in our design and operational activities that it’s really difficult to capture how do we make sure that the next generation doesn’t forget those.

Thats not an easy task. When we develop our lessons learned from accidents and failures, we need to find homes for those things that include not only the lesson itself but some reference to show you where it came from and why its there so that people understand that thats not something you can violate, you can waive, without discussing and understanding why its there. Just putting the rule in there doesnt necessarily prevent people in the future from having a problem.

Human nature is such that in the “yes/if” mode that I talked about is better—yes, you can do this if you can come up with an approach that matches that rule that you’re trying to waive or deviate from. I know that’s going to happen in the future. We’re not a rule-driven organization, and when people do challenge the rules and the regulations, they need to do it from a knowledge base that captures the real lesson learned, not just what the rule says, but why it’s there and why it got there in the first place. That’s a lot of effort to put a system like that into place.

There are people who have done it well. The mission operations people in Houston, for example, have, because of the Atlas accident, which was not a human spaceflight thing. But because of that accident, the mission operations people in Houston decided that from now on the flight rules that we live by for human spaceflight will have not just the rule, but a little italicized rationale behind that rule, right in there with the book, so that everybody reading that rule will see why it’s there.

It’s hard to capture the entire why. Sometimes the “why it’s there” could be a volume. But in two or three sentences they capture the essence of it and maybe a reference to something else. That’s the way they tried to deal with that lesson learned. There are other ways to do it. Training, of course, is a big piece of that, making sure that people who are qualified as operators understand the rules they live with, not just what they are, but why they’re there.

Download the full publication as an EPUB, MOBI, or PDF.