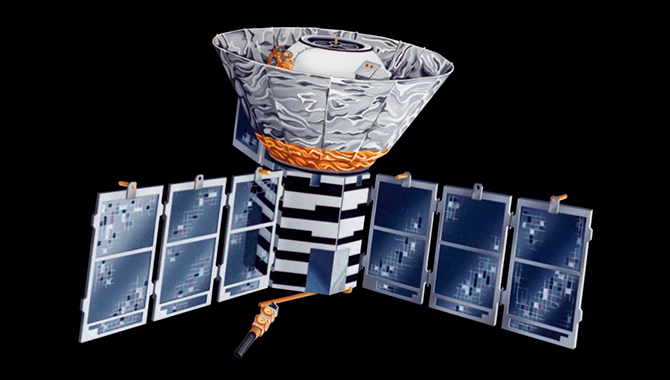

Artist's Conception- Close Up

The Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) spacecraft is the predecessor to the WMAP Project. COBE was launched by NASA into an Earth Orbit in 1989 to make a full sky map of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation leftover from the Big Bang. The first results were released in 1992. COBE's limited resolution (7 degree wide beam) provided the first tantilising details in a full sky image of the CMB.

Photo Credit: NASA/COBE Science Team

I’ve made plenty of mistakes, and some were instructive.

When I was a grad student at Berkeley, we were preparing to launch a balloon payload, which was to be my thesis project. We wanted to measure the spectrum of the cosmic microwave background radiation, the remnant of the Big Bang. Out there on the launch pad—fortunately before launch— the telemetry antenna fell off. I was the one who had soldered it on. It was a reminder that there’s always somebody who knows more than I do about almost anything, and I should always ask for help when I’m not sure. Also, and this is more important, in a large project I should definitely stay away from tasks that belong to other people. Taking them on annoys the people, undermines their responsibility, and replaces their good work with my iffy efforts

We learned something else from that balloon flight. My thesis advisor, the other grad students, and I decided to launch the first flight of this mission, even though we hadn’t tested absolutely everything we could think of. It seemed a reasonable decision because some things were not testable and none of us had prior experience with balloon payloads. As it turned out, the payload failed to function in three different ways, all of them fatal, and I had to write a thesis that was mostly about a failed piece of equipment. Two of the failures were related to the low temperature at a flight altitude of about 140,000 feet. At –70˚ C, a capacitor in the detector preamp didn’t have enough capacitance, and the preamp started oscillating. Also, at that low temperature, the drive electronics for the motor that moved the mirror failed. After the flight, my fellow grad student David Woody built a dry ice cold chamber to find out what happened. It was a simple plywood cube lined with Styrofoam boards. He put in the payload, he put in dry ice, and sure enough the flight problems appeared. We also discovered that water could get into a stepper motor and rust the rotor, reducing clearances to zero and preventing motion. The apparatus was cooled by liquid helium, and the motor was on the top, where the escaping cold helium gas could make the motor cold. In the sweltering evening humidity of Palestine, Texas, a little chill made the top of the apparatus soaking wet. It didn’t take much for some of the water to get into the motor. Back in the indoor lab, these conditions never would have happened.

What did I learn from this? Number one, if you don’t test the equipment, it probably will not work. I think you should behave as though there’s no chance of success if there’s no test. Nature knows when you’re trying to cheat her. Good project managers will always be cautious about flying something that has not been fully tested, and the funding agency needs to be aware of why.

There’s another mistake I need to tell you about. One night during the design phase of the COBE satellite, I woke up in a cold sweat. I had conceived a design for the external calibrator body, which would simulate the radiation we expected to measure from the sky. But that night, some part of my mind worried about whether the calibrator would get cold enough, and I realized my design concept was defective. The next morning I called the engineering colleague who was working on the design and explained my error. She and I worked together to find a solution, and in the end it worked.

What did I learn from this mistake? Number one, don’t trust the boss, especially if you are the boss. Nobody will be checking your work if you don’t. That’s especially true if your team likes and trusts you. If something really, really matters, it is your obligation to get an independent check. We were lucky that time. But we have to earn our luck in this business.