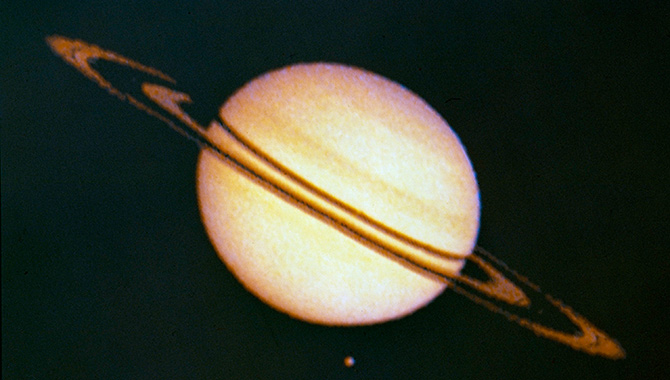

Saturn and its largest moon, Titan, seen from Pioneer 11.

Photo Credit: NASA/Ames Research Center

On September 1, 1979, Pioneer 11 made history as the first spacecraft to fly by Saturn. Its journey paved the way for Voyager—but dashed hopes of finding life on Titan.

Pioneer 11 headed toward Jupiter on April 5, 1973, leaving Cape Canaveral aboard an Atlas-Centaur rocket. The small spacecraft—only 2.9 meters at its longest point—was following in the footsteps of its sister, Pioneer 10, which had launched a year earlier. Both spacecraft would make history at Jupiter: Pioneer 10 as the first to fly past the planet, Pioneer 11 as the vehicle to travel closest to it. Ultimately, Pioneer 11 flew a mere 43,000 kilometers (km) above Jupiter’s cloud tops, becoming the first spacecraft to map its polar regions. Despite the dangers of traveling so close to the notoriously radioactive planet, Pioneer 11 had little choice. It needed to get as near as possible to leverage Jupiter’s massive gravitational pull as a slingshot that would send it across the solar system toward its next target: Saturn.

The Pioneer program was approved by NASA in 1969 as a series of low-cost exploratory missions that would return valuable information on the inner and outer solar system. But Pioneer 11 eventually developed a second focus: to mark a clear path through the environment around Saturn that Voyager 2, not far behind, could follow. Both Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 were guinea pigs for Voyager in some ways. Both flew through the asteroid belt beyond Mars unscathed, assuring the Voyager team that their more expensive, more sophisticated twin spacecraft could do so as well. Both flew close to Jupiter’s radiation belts, helping scientists understand more about their effects so that Voyager’s design could protect against Jupiter’s radiation. But only Pioneer 11 went on to Saturn.

Originally, Pioneer 11’s team envisioned a daring course through Saturn’s innermost rings to learn more about their composition. It was a dangerous proposition because if the material in the rings were too large or too small, the spacecraft would not survive the encounter. The knowledge to be gained, the team believed, was worth the risk. Voyager 2, in contrast, intended to travel through Saturn’s outermost A ring, which would bring it just close enough to Saturn to get the gravitational assist it needed to go on to Uranus. Despite the potential value of learning more about Saturn’s inner rings, NASA ultimately decided to use Pioneer 11 to blaze a trail through the A ring, determining whether Voyager 2 could travel through the ring safely.

Pioneer 11 survived the journey through the outer ring and went on to become the first spacecraft to fly by Saturn, passing only 21,000 km above the planet’s cloud tops. Over the next 10 days, Pioneer 11 produced numerous “firsts.” It provided the first close-up pictures of a planet that many considered the most beautiful in the solar system. It yielded conclusive evidence that Saturn—along with Jupiter and Earth—has a magnetic field. Its instruments charted that field as well as the magnetosphere and the general structure of the planet’s interior. The planet, scientists learned, is made primarily of liquid hydrogen, and its core is small for its size. The temperature of Saturn is -180 Celsius.

Notable among its discoveries were an additional ring and two moons, one of which Pioneer 11 nearly hit during its encounter with the planet. The narrow, newly discovered ring—the F ring—was separated from the A ring by only 3,600 km, a gap that became known as the Pioneer Division. Pioneer 11 also determined that there are numerous particles between some of the rings, and that the gaps between them, which look clear from Earth, are not.

Despite the value of Pioneer 11’s findings, one discovery was crushing. Scientists had theorized that Saturn’s planet-sized moon, Titan, might harbor evidence of life. But Pioneer 11’s measurements of Saturn’s interior heat radiation made clear that Titan was too cold to support life, a finding that disappointed many.

Pioneer 11 did not stop exploring after its encounter with Saturn. The spacecraft went on to study solar wind and cosmic rays as it traveled farther from Earth. In 1990, it flew beyond Neptune, marking the beginning of a new journey toward the edge of the solar system and, eventually, interstellar space. Over time the spacecraft’s power sources faded and the team shut down its instruments one by one. Eventually it lacked the power to rotate its antenna toward Earth and communication was lost. The last signal from Pioneer 11 was in November of 1995. The craft itself continues on its journey.

While those of us on Earth may never know how far it travels, Pioneer 11’s work may not yet be done. Both it and its sister spacecraft, Pioneer 10, feature a 6” x 9” plaque depicting the launch date of the craft and its planetary origin. Two human figures, a man and a woman, are portrayed to indicate the type of creature that created the Pioneers. The man’s hand is raised to suggest good will. The plaque is attached to the spacecraft’s antenna support struts and may be seen someday, somewhere, by something.

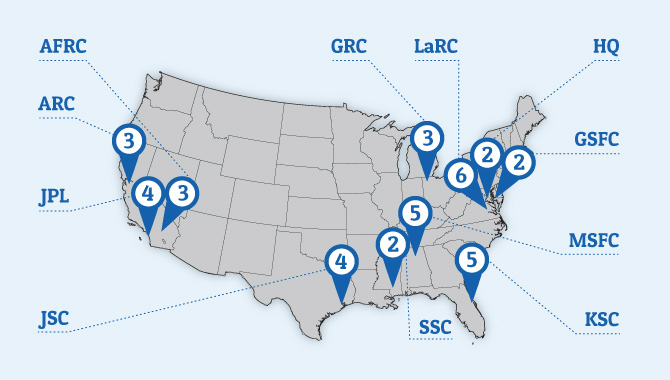

The Pioneers are managed by Ames Research Center.

Watch a video highlighting Pioneer 11’s planned journey, launch footage, and more.

View an image of Pioneer 11’s plaque, mounted on the vehicle’s antenna support struts.