By Sylvia Cox

As Deputy Mission Manager on Lunar Prospector (LP), I had periods where the cost constraints and the inherent difficulties of space hardware development made me wonder if we were going to get this project off the ground.

The Concept Definition Phase was rocky. It was the first competitively selected Discovery project, and so the process for gaining approval to move into development needed to be defined. In addition, the Contractor team was slow to coalesce into an efficient team. The core management team consisted of two NASA team members (Mission Manager and Deputy Mission Manager) and two contractor team members [Principal Investigator (PI) and Project Manager]. As the team prepared for the independent review that would allow us to move into development, several major design/development/test issues remained undecided. To further complicate matters, the first demonstration launch of the proposed Lockheed Launch Vehicle had failed.

Three weeks before that independent review, the contractor, thankfully with the PI’s strong concurrence, replaced the Project Manager. The first thing the new Project Manager, Tom Dougherty, did after joining the team was bring everyone together and address the immediate task of getting through this review. “We need to approach this review as an opportunity and not see ourselves as being on trial,” he said. “We should use the expertise of the review committee to provide us input on potential trades and solutions for development. We want to have them help us with our problems.”

It seemed to me an incredibly startling thing to say. Startling for it was so different than the crisis mentality that afflicted the project before his coming on board. In addition, it was so different from the apprehension with which I had seen reviews treated on other projects. We all knew that several areas of design would not be completed by the date of the review. We expected to be raked over the coals for this by the reviewers. I personally was extremely concerned about the team’s performance in this review, but Tom’s positive attitude and motivational management style instilled in us a confidence we hadn’t known as a team until then.

As it turned out, Tom also had a powerful affect on the review committee. Despite their concerns, his genuine openness and collaborative approach convinced them that we were committed to delivering on this mission. Based on the independent review team’s recommendation, LP moved into development in a few months. Not long after that, our invigorated team had a point design to work with and had begun long lead item procurements and finalizing the detailed design.

Attitude Was Only Half of It

But it was more than just a change in attitude that took place when Tom took over as the project manager. Under Tom, the emphasis of the entire project was on informed, timely decision making based primarily on a system of frequent reviews, and on systematic and simple monitoring systems.

The project was very constrained in cost and schedule. Given a little over two years to complete all phases of design and development, the LP team had to deliver five new science instruments, a spacecraft, and a launch vehicle in time for launch. To meet these objectives required a management team that was not only compact but also clearly focused. Our four-person management team evolved into a cooperative decision-making body that dealt with problems quickly and confidently. This was critical in taking advantage of the many practices Tom put in place. The most significant of these involved the use of weekly subsystem reviews. One day a week was set aside for these reviews. Everyone on the team had to be available to immediately work problems and resolve issues that came up in them. The team all kept working on their assigned tasks, but if, and when, it was necessary, we were available to converge on a problem to solve it together, and we began working problems on the spot.

We also had a two-hour meeting once a week where the whole team received a status on project accomplishments, key issues and overall project process. In this meeting, we reviewed the status on all open action items. Cost and schedule concerns were openly and freely discussed, and Tom sought input from anyone who wanted to either comment or ask questions. These meetings also allowed us to coordinate other meetings or address specific problems with all the necessary parties right there in the room.

These team meetings served as a forum for open discussion of issues and paved the way for better communication and reporting with the NASA Program Office. Tom wanted a policy of complete openness between the government and the contractor, and within the entire LP team. All meetings were accessible; all written reports, including the contractor’s internal status reports to their management, were available to the government.

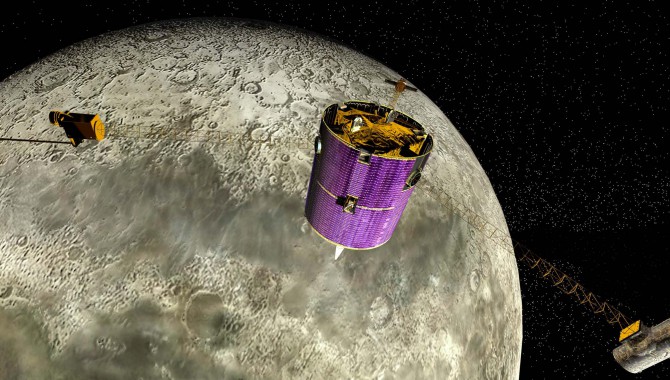

NASA’s Lunar Prospector is readied for launch as its gantry-like service tower is rolled back at Cape Canaveral Air Station Launch Complex 46.

Another important practice he put in place was allowing subsystems to go through individual Preliminary Design Reviews and Critical Design Reviews and to move ahead, if there were no apparent implications to the rest of the system. This allowed portions of the project to move ahead if they were ready to proceed, and helped to control cost and minimize potential schedule slips.

To assess the progress of each subsystem and major task, Tom established metrics for measuring performance that set minimum monthly milestones. This was not a full performance measurement system, but a method of monitoring progress without the burden often associated with these systems. If milestones began to fall behind, the management team knew it immediately from the Monday subsystem review.

In addition to this, each week employee charge numbers were evaluated to determine which organizations were charging to the project and to provide a sanity check regarding the appropriateness and reasonableness of the charges. Were there tasks ongoing in those shops or groups? Were those skills really being used at that time? Once established this was not all that time consuming, as unexpected charges were easy to spot and check.

In an organization of any significant size, controlling charge numbers is critical to controlling costs. In large companies sometimes, there may be a temptation on the part of some support organizations to generate a fixed level of income on a weekly basis from every charge number they can identify. Such issues were dealt with on the same day, and parties were required to support specific charges for that week or remove them.

Mission Accomplished

A new Project Manager can have a major impact on the dynamics of the mission. In the case of LP, the change of one key individual in the management team completely transformed the dynamics in the group. The change in the LP team dynamics with the change in Project Manager was nothing short of miraculous. Energy and motivation were revitalized. The outlook of the entire team, both NASA and contractor, was different from the day he got there.

The success of the mission is perhaps the biggest demonstration of the results of the changes that were made. LP was launched successfully from the Cape in January 1998. The one-year primary mission was completed in January 1999 and the six-month extended mission ended with the de-orbit of LP into the area of the lunar South Pole at the end of July 1999.

My LP experience was an extremely valuable one for me in a whole variety of ways. I learned that a single change in the management team could turn a project that is struggling into a fully functioning, successful team.

Lesson

- Openness and transparency between government and contractor engenders a spirit of teamwork and can have a transforming effect on a lackluster team’s performance.

- Simple and frequent review meetings allow quick responsiveness. Not everyone must participate, but they must be available. It can be done quickly and allow for quick feedback and continuous monitoring of cost and progress.

- There is no need to delay a segment of a project due to another segment. Allow subsystems to proceed according to their readiness.

Question

In this story we see that building trustful relationships between government and a contractor can be a win-win situation. But what are the difficulties in accomplishing this? Please share with us your own examples of cultivating a trustful relationship between government and contractors.

Search by lesson to find more on:

- Reviews

- Partnerships