By Michael A. Spatola

In the middle of winter in 2005, Art Pyster, SAIC’s director of systems engineering and integration, sponsored a companywide workshop to develop strategies for improving workforce management and collaboration. I was not expecting to do more than participate in the workshop, and I looked forward to the sessions, which would address both program management and systems engineering. Little did I know that as a result of this workshop bringing together by chance the director of systems engineering and the director of learning and leadership development, my job would change entirely.

SAIC, which provides scientific, engineering, and other technical services to the U.S. military, has a strong tradition and emphasis on project management. We also have a deep- seated culture of independence and an entrepreneurial spirit (“a thousand companies in one”). That tradition led to strong corporate support, training, and approaches dedicated to “Excellence in Program Management” and excellent but sometimes independent practices and initiatives within line organizations. When Ken Dahlberg took over as SAIC’s chief executive officer, he was clear in his first direction for program management: “Get our program managers better training.”

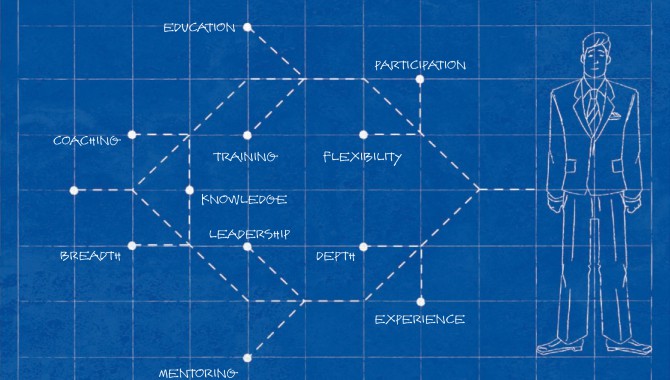

Easier said than done. We wanted this to be a collaborative effort across the company and raise our program management (PM) development to the next level. To define “better training,” we created a small planning team — which I led as the overall program manager — and a PM Advisory Panel, comprising senior program managers from across the company. The team given this task believed the only way to substantially improve PM training was to go back to first principles to figure out what makes for program management excellence, and we took a leap of faith, hoping management would understand the value of that approach. The guiding principles we created for improving our PMs were as follows:

- Competence in program management is developed through education, training, and experience with mentoring and coaching. You need all three.

- Program management professionals can be developed and advanced along a flexibly defined career path. There is more than one way to gain the education, training, and experience needed to be a successful program manager.

- Program managers need to develop broader expertise through technical, functional, line, and other roles. PMs need both breadth and depth.

Once we established our guiding principles, we needed to create a competency model that clearly defined the knowledge, skills, and attributes our PMs needed to be successful. With that model, then, as our foundation, we could (and had to) design a curriculum and career path that helped program managers acquire that knowledge and those skills.

The first version of the SAIC PM Competency Model was ready for review by the end of May 2005; then it went through three months of review, comment, and update. In a company of more than 44,000 employees, we were faced with a “review, comment, and update” process across six organizational groups and twenty-four business units. We also held review sessions with our PM Advisory Panel, keeping in mind the members were from different locations and offering them different times to participate so the PMs on the West Coast could contribute. Sending out material a few days in advance, we used a Web-based DataExchange system, audio teleconference, and projection systems to help our discussions and ensure everyone was looking at the same information. To get the best participation possible, we would schedule several opportunities for them to join the discussion.

We also wanted feedback from our line managers, and we were smart enough to realize they already had many demands on their time. To ensure we got their feedback without taxing their workloads more, we sent our preliminary drafts to line managers’ key staff, asked our PM Advisory Panel members to help notify line managers about the materials, and set up several discussion sessions for them. We also offered to meet with any business unit general manager who could not attend a discussion session.

One lesson we learned from the comments we received was that how the model was displayed was just as important as what the model displayed. Because of that, we reexamined the model from a communications point of view and adjusted it so we had several versions for different audiences. Looking back at our process, our keys to success were

- Recognizing that PMs need to have both leadership and management skills, which resonated across the company

- Considering SAIC’s company values and needs, which established a model consistent with our culture

- Evaluating appropriate external sources, which added credibility to the final results

- Realizing that the skills a PM needs vary by project size and complexity, which allowed a fuller look at what we really need in a PM

- Identifying competencies by project type aided in developing a curriculum, which focused on the right training for each type of project

Using the PM Competency Model as the foundation, we created a “map” that showed what courses we had and which competencies they helped support. Historically, SAIC had emphasized internal program management courses that were both developed and taught by SAIC experts. But the “state of the practice” for program management as well as our own internal processes had grown and evolved to better meet the needs of practitioners and customers. Unfortunately, not all of our internal courses had kept pace.

To make sure our courses reflected “better training,” and recognizing our limited internal resources to both develop and instruct courses, we kept in mind the following:

[picture]Because our stakeholders felt the working relations and review processes we used for the PM Competency Model were disciplined, fair to all, and complete, we used it again for developing our curriculum. Our first major review of the curriculum from the line organizations had more than 300 comments, which was a huge response. In addition to responding to this feedback, having representation from senior-level (seasoned) program managers from across the company was critical to our success. And we would not have succeeded without participation across the company throughout our efforts. That participation kept interests high, ensured real needs were identified and met, and aided buy-in to solutions to those needs — all of which were key.

Releasing the new PM curriculum represented a philosophical change in SAIC’s approach to project and program management training: external vendors, more training, increased training costs, and more. And as the first classes were held, e-mails hit my inbox and the phone started ringing with an overwhelmingly positive response to what we had done. I could tell our long journey to success had really just begun, and that there is much more to come in the future.