By Dr. Ralf Müller

Analyzing extensive questionnaires completed by 400 project management professionals, Professor Rodney Turner of the Lille Graduate School of Management and I have identified competencies that contribute significantly to project management success. Our research helps define the managerial and emotional competencies needed to make projects work. We also found that different kinds of projects call for different combinations of competencies.

While some commentators focus on project tools and techniques, Aristotle knew thousands of years ago that effective leadership depends on the social competencies needed to form good relationships and evoke common values. The fact that fewer than 50 percent of projects succeed in achieving their aims on time and on budget suggests that even the best tools won’t do the job in the wrong hands. Our research shows that Aristotle was right about the kinds of competencies successful leaders— including project leaders—must have.

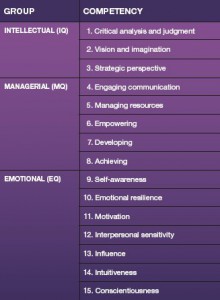

Earlier research suggests that a manager’s leadership style can be defined in terms of emotional (EQ), managerial (MQ), and intellectual (IQ) competencies. (See table on facing page.) We found that emotional competency correlates significantly with project success in high-performing projects of almost all types. The higher the EQ, the higher the level of project success.

However, different kinds of projects require different competencies. In engineering and construction projects, conscientiousness, interpersonal sensitivity, and engaging communication contribute most to project success. This is because of the need for discipline and due diligence in managing these complex projects and also because of the need to evoke and integrate various opinions and possible solutions to problems.

For IT projects, the important competencies for success once again include engaging communication, along with selfawareness and developing resources. Finding the right “tone” with others, together with good control over personal feelings and helping project team members take on challenging tasks, are the attributes of successful leadership in these projects. This combination helps IT leaders overcome the common problems of unclear goals and low budgets on the side of the project team, and unrealistic expectations on the side of future users of the IT system.

Organizational change projects also require engaging communication in addition to motivation, an emotional competency. The project manager who rates high on motivation exhibits and encourages drive to achieve clear results. He or she actively creates the energy that major change requires. In combination with interpersonal competencies, this drive is essential for managing reorganizations or implementing new work processes.

We found that one competency correlates negatively with success in all high-performing projects: vision and imagination, an intellectual competency. Visionary and imaginative people are without doubt important to project success, but when the project manager is too imaginative he can compromise the task at hand. Conscientiousness is much more important to successful project management than vision. Vision and imagination are better supplied by people in other roles, such as the project sponsor, who sets and communicates a project’s objectives.

These findings suggest that project managers should think consciously of the specific skills their particular projects call for, and leaders should pay careful attention to matching projects and project managers, developing project managers with the skills appropriate to the work they will be doing. It is commonly thought that IQ is somewhat fixed after the age of twelve. EQ and MQ, however, can be developed throughout life.* That makes it possible for people to learn the competencies that suit the needs of a particular project type.

But developing the intellectual, emotional, and managerial competencies that effective project managers need takes time and focused effort. Reading a book on communication does not make a person an “engaging communicator,” and managers do not become experts in motivating others simply by realizing that motivation is important. Cultivating these and other competencies often requires open feedback from coworkers or mentors over an extended period of time to identify areas for improvement, followed by training and extensive practice to improve in the desired area.

But developing the intellectual, emotional, and managerial competencies that effective project managers need takes time and focused effort. Reading a book on communication does not make a person an “engaging communicator,” and managers do not become experts in motivating others simply by realizing that motivation is important. Cultivating these and other competencies often requires open feedback from coworkers or mentors over an extended period of time to identify areas for improvement, followed by training and extensive practice to improve in the desired area.

The effort is worthwhile, though, because good project management is much more than tools and techniques. Matching project needs to emotional, managerial, and intellectual competencies is neither a panacea, nor the only way to improve project results. It supplements existing ways of selecting project managers for projects. Most importantly, it moves the discussion from what to do in projects to how to behave in projects. Isn’t that something we learn from early childhood on? Finally, that approach is making its way into project management.

This article is based on joint research done with Professor Rodney Turner, Graduate School of Management, Lille, France. The researchers acknowledge the financial support from the Project Management Institute (PMI), the Graduate School of Management, Lille, and the School of Business at Umeå University. Without this support the study would not have been possible.