Baniszewski talks about one site of the Battle of Gettysburg, Little Round Top. Photo courtesy John Baniszewski

By John Baniszewski

George graduated with a degree from one of the finest engineering colleges in America and immediately went to work for the government. For several years, he worked staff jobs. His career took off when his organization put him to work on projects.

The projects George worked on were for state-of-the-art communication systems, which had to operate dependably in harsh environments. The primary payloads for these projects were expensive and complex optical systems that had to be integrated with support structures that provided for energy, command, and control. The success of these projects sometimes depended upon unproven manufacturing processes. When the manager of his first project unexpectedly died, George succeeded him and completed the project on time and within budget, meeting all technical requirements. George’s bosses recognized his talents. During the next decade, he managed another nine similar projects, consistently meeting his technical, schedule, and budget goals.

There came a time when his organization faced a crisis. A series of projects had failed, and the organization’s existence was in jeopardy. The biggest and most important project was a mess—the senior project team members were fighting among themselves, and the project manager was floundering. Senior management sacked the project manager at a critical stage of the project and put George in charge. Within days, he turned the project around and achieved one of the biggest successes in his organization’s history.

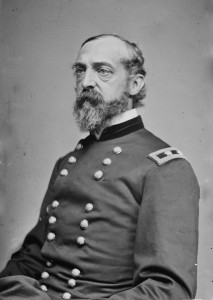

The project manager’s full name was George Meade. He graduated from West Point in 1835. In the 1850s, he managed the construction of lighthouses along the Atlantic coast. He was an officer in the Union army during the American Civil War. In June 1863, a Confederate army led by the legendary Robert E. Lee was marching through Pennsylvania, and Abraham Lincoln feared the end of the United States of America as a country. On June 28, 1863, Lincoln put Meade in charge of the North’s largest army. Three days later, the Battle of Gettysburg began. On July 3, when the guns fell silent, George Meade and his army had won the most decisive battle in American history.

George Meade defeated Robert E. Lee, one of the greatest military leaders of all time. How did he do it? By using the skills he had learned as a project manager and outperforming Lee in all aspects of project management.

I work at NASA Goddard as a deputy project manager for resources. I am also a licensed battlefield guide at Gettysburg. A few years ago, the Defense Acquisition University asked me to develop a training program that uses the Battle of Gettysburg as a case study in project management. I have taken dozens of project managers to Gettysburg in connection with this program.

Most project managers are familiar with the Project Management Institute’s “Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge” (PMBOK), which identifies the skills and knowledge crucial to successful project management. An analysis of the Battle of Gettysburg shows that George Meade completely outperformed Robert E. Lee in seven of the areas identified in the PMBOK: project integration, scope management, time management, resource management, human resource management, communication, and risk management. Meade’s superiority over Lee in these areas was critical to the North’s success at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Project Integration

Project managers need to make sure that all the elements of a project work together. They must develop and execute plans and coordinate changes to those plans. Meade’s predecessor had kept his subordinates in the dark. As soon as he was promoted, Meade found out everything he could about the condition and status of his army. He developed a well-coordinated plan for the movement of his scattered soldiers to simultaneously protect key northern cities, bring the southern army to battle, and allow his army to consolidate quickly where the fighting would break out. When the fight started three days later, he sent trusted subordinates to take charge of the fighting. He knew his job was redirecting the movements of his scattered army to make sure the efforts of his entire army were coordinated. Because of him, all 90,000 of his soldiers knew where to go and when to get there. They got there in record time. Each day of the battle, he gathered all his key subordinates together to ascertain the progress of the battle, to ensure everyone knew what was expected of them, and to revise plans for the subsequent day.

Robert E. Lee, in contrast, was completely surprised by the start of the battle and played no role in deciding when or where it would occur. He allowed his subordinates to talk him out of repositioning their soldiers, resulting in one-third of his army having little ability to affect the battle decisively. During the entire three days of fighting, Lee never had his three key subordinates in the same place, at the same time, to share information and ensure cooperation.

Scope Management

A project manager must define the scope of the work, break it into manageable pieces, verify and control what work is being done, and make sure that the work being done is essential to the project. One of the biggest causes of Lee’s defeat was the southern cavalry soldiers’ failure to do their most critical job: collect intelligence about the enemy. A week before the battle, Lee allowed his cavalry commander, General J.E.B. Stuart, to go on an ill-planned mission that crippled Lee’s ability to gather information about the Union army. They wasted valuable time capturing supplies instead of focusing solely on their primary mission of scouting. As a result of this “scope creep,” Lee’s cavalry failed to play the role for which it was most needed. Lee went into battle knowing very little about the strength of his opponent and made key decisions with inadequate knowledge.

When Meade took command of his army on June 28 and ordered its advance, he had to separate it into several pieces to carry out all his requirements. Meade made sure that his subordinates did exactly what he wanted done by sending them frequent orders about the direction of march, number of miles to advance, and destinations at the end of each day. He monitored their progress closely. If his subordinates failed to reach their daily objectives, he chastised them mercilessly. He made sure their independent movements were completely in compliance with his master plan. He resisted pressure from Washington to send his cavalry chasing General Stuart, knowing that he needed his cavalry to focus on the crucial role he assigned it. Thanks to Meade’s efforts, he was able to achieve an incredibly rapid concentration of his soldiers and fight the battle with an advantage of numbers.

Time Management

Every project manager knows the challenges of schedule and the value of schedule slack. The key to victory in the Civil War was to get soldiers quickly to where they were needed—the battlefield. Meade had his men march an average of twenty miles a day for three days. Twelve miles a day was considered challenging. Supply wagons were ordered off the roads so they would not impede the combat soldiers’ march.

In contrast, Lee did not seem overly concerned about the speed of his army’s concentration once he knew a battle was likely. His official report said that “the weather being inclement, the march was conducted with a view to the comfort of the troops.” At one point, 12,000 of his best combat soldiers were stopped dead for hours, blocked by supply wagons at a road intersection, greatly delaying their arrival at Gettysburg.

Resource Management

Project managers must get the resources they need and use them effectively. Meade’s critical resource was combat soldiers on the battlefield. Meade knew the value of keeping a reserve. On day two of the battle, he kept 20 percent of his combat soldiers and 25 percent of his cannons as his reserve, to be used as needed. One of Meade’s incompetent subordinates disobeyed his orders and moved his troop to a weak and vulnerable position, where they were hit with a devastating surprise attack by 15,000 Confederates. Meade immediately threw in his reserves, sending them where they were most needed, and shifted other resources from places where things were quiet. His prompt action prevented a disaster.

The Confederates never had additional troops where and when they were needed. When one of Lee’s subordinates, James Longstreet, was on the verge of a breakthrough, he needed additional resources to ensure victory. None were there. He later complained, “We received no support at all, and there was no evidence of cooperation on any side.”

Baniszewski talks about one site of the Battle of Gettysburg, Little Round Top.

Photo courtesy John Baniszewski

Human Resource Management

Project managers get the people they need and use their talents to achieve mission success. George Meade knew the importance of using the right people for the right jobs. As a condition of accepting command, he demanded and got authority to promote, demote, and use his generals as he saw fit, based on their ability and competence. When Meade ordered his army to march northward, he informally reorganized it, putting almost half of it under the control of his most competent subordinate. When that man was killed in the fighting, Meade sent his most junior subordinate to take command, a general named Winfield Hancock, who had proven his skills on many past battlefields. Hancock performed superbly.

Lee’s team had undergone major turnover. Stonewall Jackson, his best general, had been killed two months before Gettysburg. Lee promoted two men to take Jackson’s place: Generals A.P. Hill and Richard Ewell. Lee had always used a “hands-off” management style that worked well with his previous team. It did not work with Hill and Ewell. Time and again, they failed to act when Lee expected action, or they took actions that Lee had not authorized. They were not ready for the independence Lee gave them. He did not give them the clear direction they needed.

Communication

Projects generate huge amounts of information. A key to project success is getting sufficient and accurate information to the people who need it when they need it. Meade had a centralized organization, the Bureau of Military Information (BMI), to collect information from hundreds of sources and turn it into knowledge that could be used to make decisions. This organization was located fifty yards from Meade’s headquarters, and he continuously called upon it to apprise him of the status of both armies.

Lee had nothing comparable to Meade’s BMI. He himself, assisted by a handful of aides, assumed responsibility for collecting and interpreting the information needed to prosecute the battle. Lee had little idea of the extent of the casualties his army suffered. On the last day of the battle, he ordered an attack in which he significantly overestimated the size of his attack force. That attack was a disaster. At Gettysburg, Meade had access to important information and used that information to make smart decisions. Lee’s lack of comparable information led him to make crucial mistakes.

Risk Management

Project managers must identify and quantify the risks that jeopardize project success and make plans for dealing with them. Meade always considered what might happen if his plans went awry. On each day of the battle, he developed detailed contingency plans and was always prepared either to attack, hold his ground, or retreat. Meade never had to make use of these plans, but they were there if needed.

Lee seemed to operate under a constant expectation of success. In the case of the disastrous cavalry expedition made by J.E.B. Stuart, Lee had other cavalry soldiers that he could have used to fill Stuart’s role. Instead, he sent those soldiers on other, lesscritical missions. Lee made no plans to address failure in battle. At the end of day three, when he finally understood the horrible extent of his losses and realized that his army was in danger of destruction, he had no retreat plan to draw on. Had Meade been more aggressive on July 4, Lee’s army could have suffered disaster due to Lee’s lack of planning for a battlefield setback.

Learning from Meade

Studying Meade and Lee’s performances at Gettysburg can help modern project managers appreciate, develop, and use the skills they need to be good project managers. The circumstances may be different, but the basic principles are the same. This dramatic event in American history shows how the skills of project management can be used in almost any situation. Former project manager George Meade used those skills to change the tide of the Civil War.