September 30, 2010 Vol. 3, Issue 9

“Whoever comes are the right people. Whatever happens is the only thing that could have. When it starts is the right time. When it’s over, it’s over.” *

No agenda. No keynote speakers. No audience members in rows of uncomfortable chairs fidgeting through serial PowerPoint presentations.

After a debut event last February in San Diego, SpaceUP made its way to Washington, D.C. in August. SpaceUP breaks the typical conference paradigm of mediocre food, large registration fees, and rigid lecture schedules. It engages and motivates all attendees to participate because they want to, not because they have to.

I had never been to an unconference. Quite frankly, the concept made me uncomfortable. But as I discovered, that’s the point.

Nothing is pre-arranged at an unconference. The participants bring the topics, choose the time and place, and spark the discussion. If you aren’t in a place where you can contribute, you go somewhere where you can. At an unconference, no one gets to be a fly on the wall (my usual modus operandi). Everyone contributes.

As I introduced myself to people filling up the main room of Funger Hall at George Washington University, I found that participants hailed from all over: California, Minnesota, Florida, and Texas, as well as the DC area. Some worked in the space industry. Some didn’t. Participants ranged from a nine year-old to retirees. Most had never been to an unconference. All were space enthusiasts. We were an odd bunch, but, as I would come to find, a thoughtful, inspiring, and intelligent group dedicated to space exploration.

“This is kind of a weird experiment,” unconference coordinator Michael Doornbos told us. While the discussions over the next two days were bound to be productive, he reminded us that SpaceUP is about taking what we discuss and doing something after we’ve all gone home. “SpaceUP isn’t a destination,” said Doornbos. “It’s a springboard.”

Session board for SpaceUP DC on Day 1. Credit: Cariann Higgenbotham

The unconference revolved around a large board with a grid showing open time slots and rooms. Next to it were piles of Post-It notes and Sharpie pens. After Doornbos’s introduction we left the main room for the board. We stood around it like eighth-graders at a dance, anxiously waiting for the first brave soul to get things started. But it wasn’t long before Post-It notes began filling up the empty spaces: “Space Solar Power Policy,” “Suborbital Markets & Disruption Theory,” “Nuclear Rockets,” “Reaching a Larger Audience (minorities),” and “Innovative Uses of the ISS.”

Then the group scattered. This is how it starts, I thought. Engineers, designers, educators, scientists, writers, parents, grandparents, and kids were going to discuss space policy, nuclear rocket engines, reinfusing the aerospace workforce, innovation, technology development, and grand space challenges. If you couldn’t participate in person, you could participate virtually. Every room was equipped with live video, audio, chat, and wiki capabilities. If you missed a specific talk, the videos were online the next day. Heading off to my first session, my own discomfort with the lack of structure melted away. At an unconference, everyone is on even ground. To solve big problems, everyone needs to contribute. As with brainstorming, every idea counts.

One of the first talks I attended was by Amy Kaminski from NASA’s Participatory Exploration Office. She sought input on what NASA could do better to engage the public its missions. With $5 million in the FY 2011 budget for her office, she wants to make every penny count. One participant suggested that NASA make participatory exploration a priority for missions. This will require a shift in culture, but these missions exist to help people learn, she said. Participatory exploration is just as important as the science coming out of the mission. Be nimble with your approach, said another participant. What worked to engage the public the first time may not work the second and third.

Emory Stagmer, a satellite flight software lead engineer for Northrop Grumman who worked on the LCROSS mission, hosted a session on nuclear power. He became interested in the topic after receiving several books on the topic for Christmas, and has been a proponent ever since. Our discussion determined that the promotion of nuclear-powered spacecraft faced three main obstacles: international diplomacy, leadership buy-in, and changing the public’s perception of nuclear technology.

Justin Kugler, a systems engineer for SAIC working in NASA’s ISS National Laboratory Office, continued Stagmer’s discussion with his session, “To Mars and Back in 80 Days.” Kugler said there was a need to “start talking about new and innovative ways to do propulsion.” New propulsion methods could be implemented gradually as redundant systems on science missions or on small-scale demonstration missions.

Above: Group shot of SpaceUP DC participants on Day 2 of the unconference. Credit: Dennis Bonilla

“Free range rocket scientist” and educator Tiffany Titus, who just moved to the Space Coast of Florida, hosted a session on the impact that Twitter has had on her life. Twitter is how she communicates her passion for space at a grander scale and keeps a conversation going about that passion. Cariann Higgenbottom, one of the founders of Spacevidcast, said that prior to the start of the unconference, she hadn’t met 98 percent of the people in sitting in the room in person, but she knew them through Twitter. For the vast majority of the people in the room (myself included), NASA is the reason they joined Twitter.

I co-hosted a session with Goddard Space Flight Center’s Jon Verville on CubeSats. One participant said that watching the Mars Exploration Rover landings inspired him to want build his own CubeSat in order to experience that thrill of success. Alex “Sandy” Antunes shared that he has already built one, describing it as a “midlife crisis sort of thing. I could buy a motorcycle or launch a satellite.” Called Project Calliope, the picosatellite will relay measurements taken in the ionosphere back to Earth in the form of sheet music. Musicians will be able to remix the data however they like. Antunes built the entire spacecraft in his basement. “We’re at the point where the engineering is not the hard part anymore,” he said. The challenge, we all agreed, is finding and paying for a ride into orbit.

While many other fruitful discussions took place, one particular session epitomized the spirit of an unconference. “Engaging the Next Generation of Explorers” lasted for nearly two and a half hours. By the end, the number of participants in the room doubled. Nobody left. Other scheduled activities were cancelled because nearly everyone was in this session.

There was broad agreement that there is a lack of connection between the public and space, so conversation focused on deriving the missing “X factor.” One participant suggested the need to find a way to get the public to connect with space like they do with the fishermen from the television show “Deadliest Catch.” Make it personal, and make it affect people, others agreed. “You’ve got to create moments that [people] can connect with,” said Dennis Bonilla, a graphic designer and NASA contractor. “Effective outreach is about meeting people where they are,” said another participant. Effective outreach starts with telling a story and making it one everyone can be a part of.

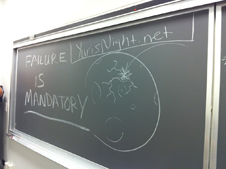

Lesson from “Engaging the Next Generation of Explorers” session hosted by Tim Bailey. (Click image for close-up) Credit: Cariann Higgenbotham

Educating leaders and children was another component of the discussion. Many participants reiterated that it has to be OK to fail. Failure is mandatory. Failure is part of inquiry, part of science, part of exploration, part of learning. Innovation is driven by failure. If this is a problem for today’s generation, it is likely to persist for the next.

In addition to the individual session, SpaceUP DC featured a series of Ignite talks, a format that allows speakers five minutes and twenty slides to share their topics. Doug Ellison from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) previewed the Explorer Engine JPL is developing that will let users explore the Solar System in a completely new style this October. “Brace yourselves,” he said. “The solar system is coming to your desktop.”

Jim Adams, Deputy Director of the Planetary Science Division in the Science Mission Directorate, went through the exciting things happening at NASA right now. “Right now, it’s raining liquid methane on Titan,” he said, encouraging the audience to “share the cool” of space exploration.

Tim Bailey shared his experiences as Assistant Director of Yuri’s Night, a world-wide celebration of the first man in space. The celebration at Ames Research Center attracted 10,000 people over two days, said Bailey. “People are interested,” he said. “They want to know what’s going on…they need to be able to connect.” Bailey encouraged the audience to get involved for the 50th anniversary of the first man in space in April 2011.

Other participants included: Kirk Woellert, a space entrepreneur, who spoke about citizen satellite opportunities; Ken Davidian, a former NASA engineer who discussed commercial space activities at the Federal Aviation Administration; and Jason Marsh, who explained his work with Copenhagen Suborbitals. The Ignite talks were topped off with a performance of “Bake Sale for NASA” by singer CraftLass.

An important aspect of the unconference was the opportunity to have fun and enjoy the things that interested us in space in the first place. We fiddled with pipe cleaners (out of which one person constructed the space-time continuum), built spaceships and rovers out of Legos (our “green” ship was powered by Lego conifers), conducted a MoonPie eating contest (beware the banana flavor), and held what is probably the first Tribble war ever (they’re not as soft as they look). If this all seems quite silly, then take a moment to think on what sparked your interest in space and what fuels it now. When did you realize that space is cool?

The conversations I was part of last August continue today. Follow-up SpaceUP unconferences for San Diego and Washington are in the works, and new cities like Houston and Minneapolis starting their own.

While getting to Mars, global cooperation in space, or pushing the boundaries of space technology all come with technical, political, and budgetary challenges, space exploration is fueled by the imagination and enthusiasm of both fifty-year-old engineers and eleven-year-old kids like Caleb Doornbos, whose disarming intelligence and freedom from limitations made us all walk away asking, “Why not?” Why not inspire the next generation about space? Why not go to Mars and back in 80 days or less? Why not launch your own satellite? Why not?

* Credit: Chris Corrigan “Open Space Technology” Flickr stream.