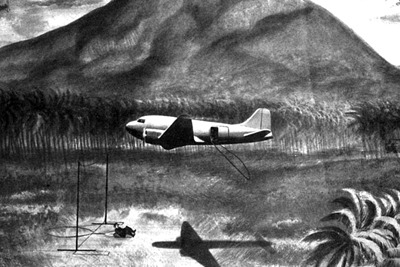

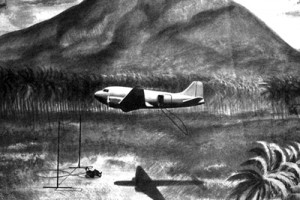

Illustration of the snatch pickup, from 1944 U.S. Army Air Forces manual. Image Credit: Central Intelligence Agency.

June 14, 2011 Vol. 4, Issue 4

Shot down, tied up, and imprisoned somewhere in China, two CIA operatives were told by their captors, “Your future is very dark.”

Illustration of the snatch pickup, from 1944 U.S. Army Air Forces manual.

Image Credit: Central Intelligence Agency.

On a clear winter night, November 29, 1952, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) operatives Richard Fecteau, 25, and John Downey, 22, boarded a plane to retrieve an informant in Chinese territory. During a second pass over the pick-up site, heavy fire from the ground brought the plane down. Their informant had been “flipped”—he had shared information with the Chinese about their mission. Shocked and confused, Fecteau and Downey, the only survivors, were immediately taken away for interrogation and imprisonment. It would be twenty years before either man would return home.

A half-century passed before the Downey-Fecteau story could be told in full. Before institutional memory could fade, the CIA captured lessons from this incredible story: the communication shortfalls that preceded the ambush; the extraordinary psychological stamina that sustained both agents; and the creative, dedicated maneuverings of the agency to provide for the men and their families during their absence and ultimately bring them home.

At CIA Headquarters, a painting of the Downey-Fecteau nighttime ambush hangs on a wall shared by images of other intelligence heroes like Virginia Hall, a World War II spy who received the Distinguished Service Cross, and Drew Dix, who singlehandedly assembled a small team and liberated the city of Chau Phu from Vietcong forces in 1968. Employees regularly stop and gaze. Not too far away stands the Memorial Wall, its 102 stars chiseled into the marble, commemorating lives lost in the line of duty. Among them is a star for Downey and Fecteau’s pilot from that November night. More than fifty years since their story began, it finally can be told—and taught.

Tale of Two Agencies

Downey and Fecteau with captured B-29 crew in a Chinese propaganda photo. (Fecteau is standing to the right of the table, reaching down for a meal. Downey stands in the center of the photo, up against the wall.)

Photo Credit: Central Intelligence Agency

The CIA, like NASA, is an organization defined by extraordinary individuals with extraordinary stories. And intelligence, like aerospace, is a tough business. Complexity and expectations rise without commensurate increases in resources. Successes usually go unheralded, while failure is subject to heavy scrutiny. And, to a certain extent, this is rightly so. Lives are on the line.

Congress created the Central Intelligence Agency with the passage of the National Security Act of 1947. Eleven years later, the Space Act led to the establishment of NASA. Both agencies grew up in the context of the Cold War competition with the Soviet Union and the perceived threat of global communism.

Both have also had their share of public failures over the last half-century. This year marks the tenth anniversary of 9/11 and the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Challenger accident—watershed events for these agencies and the nation.

Within the last decade, the intelligence and aerospace communities have had to respond and adapt to a dynamic world where information flows freely, technology is a blessing and a curse, smart networks define success, and transparency rules. While instinct may tell organizations to restrict and regulate information, taking this reality as a challenge to adapt and use the elements of the new environment to its advantage might be more effective.

Today, both agencies also face the challenges of resolving a “grey-green” generation gap. When NASA went to the moon, the average age in mission control was 26, whereas today it’s closer to 50. At CIA, over half of the workforce entered the agency after 9/11. Passing on institutional knowledge is essential.

Center for the Studies in Intelligence

Knowledge sharing is particularly challenging in an agency of silos fortified by untold layers of security and secrecy. The Lessons Learned Program at the CIA is an initiative that started in 1974 with the establishment of the Center for the Study of Intelligence (CSI). Getting to its current form today took time. In an elite, unforgiving profession, admitting, much less embracing, the possibility of failure is not easy.

Christa McAuliffe received a preview of microgravity during a special flight aboard NASA’s KC-135 “zero gravity” aircraft. She represented the Teacher in Space Project aboard the STS-51L/Challenger mission.

Photo Credit: Central Intelligence Agency

“A program explicitly designed to improve human performance implies that human performance needs improving,” wrote Dr. Rob Johnston, director of the CIA’s Lessons Learned Program, in his work Analytic Culture in the U.S. Intelligence Community: An Ethnographic Study. By gaining the support of agency leadership, Johnston was able to establish a resourceful knowledge sharing outfit. The CIA Lessons Learned Program produces case studies, oral histories, training, knowledge sharing events, and manages internal communities of practice. In a “failure-is-not-an-option” environment, having respected leaders share stories about past failures and successes stimulates learning and growth.

“It is important…that there be a voice in favor of openness to counterbalance the many voices whose sole or primary responsibility is the advocacy and maintenance of secrecy,” Johnson wrote in Analytic Culture. This balance between restriction and freedom would optimize personal efficacy. In an increasingly transparent world, where organizations are sometimes forced to learn in public, one could argue that this type of organizational evolution is necessary.

To Be Better and Do Better

Supporting organizational knowledge sharing is a way to address big questions in pursuit of mission success. How did we get those guys home? How did we respond when all hell broke loose? What did we do when we got it really right? Initiatives like the CIA Lessons Learned Program preserve valuable experience and knowledge within the institution before it walks out the door.

The Challenger and 9/11 tragedies are reminders of the necessity for organizational learning and knowledge sharing. So are the stories of Downey and Fecteau; Jim Lovell, Jack Sweigert and Fred Haise; Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee; and countless others who made extraordinary sacrifices. Their stories provide fundamental lessons for current and future generations of practitioners.

Read Extraordinary Fidelity, the full story of Downey and Fecteau.

Learn more about the Center for Study of Intelligence.

Watch the CIAs Extraordinary Fidelity video.