XFV-12A on ramp at NAA in Columbus, Ohio Photo Credit: North American Aviation

October 28, 2011 Vol. 4, Issue 8

Maciej “Mac” Zborowski is restoring the fuselage of a XFV-12A plane found in the middle of a vacant field so he can share its story with the public.

Mac Zborowski, 33, is an industrial design contractor at Glenn Research Center, who has worked on various projects since 2003. He moved to Ohio in 1986 from Warsaw, Poland. His background in industrial design and engineering has afforded him the opportunity to do everything from working on planes, developing fuel-cell powered cars, to working as a photographer in Chicago. Currently he is working at Glenn’s Power Systems Facility on a power beaming project. In his spare time, he has been dusting off a bit of history and share the story.

ASK The Academy: Youve been volunteering your time with a cadre of others on a restoration project with the fuselage of a XFV-12A. What is it and how did you get started on it?

Maciej Zborowski: The XFV-12A is an aircraft that was developed here in

Ohio by Rockwell International to take off vertically and fly at supersonic speeds. It was developed off a U.S. Navy contract in the ’70s and early ’80s. It was cancelled in ’81 and somehow, part of the fuselage—the cockpit—was found by a friend of mine in the middle of a field at Plum Brook Station in Sandusky, Ohio, which is part of NASA Glenn Research Center. My buddy was working out there and he sent me a text message with a picture of this mysterious thing. Within two days we figured out that there was only one of these in the world and we have it. The director out at Plum Brook Station, General David L. Stringer, signed it over from scrap status into artifact status. So we got our Indiana Jones whips and hats, and we’ve been restoring it so we can show off Ohio’s cool aviation research history.

Even though the XFV-12A was not a successful program, it shows you that just because you fail does not mean that you’re failing at research. If you want to paraphrase Edison, it’s not that you’ve failed 2000 times at making a light bulb, but you were successful at finding out that there’s 2,000 ways of how not to make a light bulb, and just one to make one work!

It’s a pretty neat little artifact to have in your portfolio, whether it’s Ohio or the United States or NASA. The restoration is a great project. Sometimes research can be very nebulous to nontechnical people. It’s one way of introducing someone to what research is and how it works.

ATA: Where is the plane fuselage now?

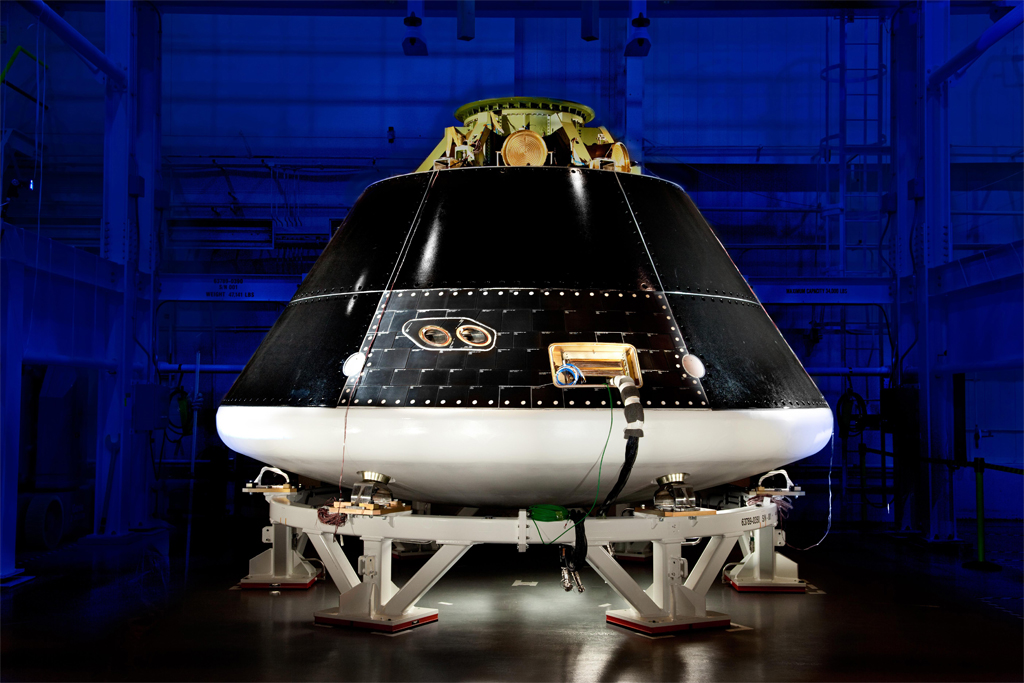

XFV-12A fuselage on a dolly out at Plum Brook Station

Image courtesy of Maciej Zborowski

Zborowski: Right now it is in the old carpenter shop, basically in a small shack out in the middle of a field at Plum Brook Station. We’ve been ripping stuff out of it and making it kid friendly—removing sharp objects and sprucing it up. I’ve been taking a scrub brush to it and cleaning it. As soon as it gets painted, it will be sent to a museum or to other facility as an interactive exhibit. We’re all doing this on a volunteer basis. To kids and people with some imagination, it’s going to be the best thing they’ve ever sat in.

ATA: Your portfolio of experience is broad. As a practiced problem solver, how do you typically approach a new challenge or experience?

Zborowski: With a sketchbook! One of my favorite things to do is draw. When you get down to it, drawing to me is imaging the problem. Imaging the solution is fine, but remembering that solution or putting that solution into some kind of coordinate system, whether it is on a piece of paper or on a computer, that is where the magic happens. So I start out with a sketchbook, pencil, paper and lots of tea or coffee. When I have a new challenge given to me, I try to learn from it as much as possible to gain as much knowledge and experiences as I can.

Throughout the process of working on the XFV-12A Ive learned a lot about different types of paints and surface treatments, and how different metals age. Ive also learned that you shouldnt put your face next to a hydraulic hose that potentially has hydraulic fluid still in it from thirty years ago!

I’ve also talked to some of the guys who were involved with the testing of the plane at Langley Research Center. Some of the modeling and dynamics research was done here at Glenn, and then they shipped the XFV-12A off to Langley to test it on a big A-frame to see if it would hover. They also studied the dynamics of the Coand effect.

ATA: What is the Coandă effect?

Maciej Zborowski, an industrial design contractor at Glenn Research Center, stands in front of the fuselage of a XFV-12A plane that he is restoring.

Image courtesy of Maciej Zborowski

Zborowski: Pretend that you are in a

car and you stick your hand out the window with all of your fingers pointing towards the front of the car, like an airplane kind of waving your hand up and down out the window. Just like an airplane wing, but with your fingertips pointing towards the front of the car. The air rushing over the top of your hand naturally creates a low-pressure area above. If you start pointing your fingertips up, so that they’re perpendicular to the road, there are eddies that come off your fingertips, and basically your hand stalls. It’s the same thing that happens to an airplane if it stalls.

In the Coandă effect, the air going over the top of your hand would stick to your hand, essentially pulling it upwards. So no matter what angle you position your hand, it would not stall.

This was what made the XFV-12A special. It used moveable flaps in the wings and canard, to direct engine exhaust though the flaps and thereby causing the surrounding air to be directed in a different direction, all the while not separating or stalling from the surface of the flap. This thing looks like something from Battlestar Galactica. It does not look like a regular airplane you’ve seen. There’s no vertical surface. It’s a pretty weird looking airplane, especially for the 1970’s. Fast-forward to today, the F-35 Lighting II is an airplane being developed by Lockheed Martin for the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Marines, and the U.S. Navy. One of the F-35 models will take off vertically and also be supersonic. Imagine the fact that they were trying to do this in the ’70s. They were barking up the right tree, they just didn’t know of the ducting losses and airflow issues they would encounter. We’re just getting around to solving that problem.

ATA: Why is it important to restore something like the XFV-12A?

Zborowski: I think that it’s a prerequisite for working at NASA. Not only are we the best of the best, but we should take every opportunity that’s sensible for us to interact with the public. If there’s an opportunity that presents itself, we should be cognizant of that, run with it, and see where it goes.

When I found out about this fuselage being out in the middle of a field, waiting to be scrapped, and finding out that it’s a prototype that is basically the definition of research, that’s when a couple of us grabbed it by the horns and decided to go do something with it.

I will admit that it’s been hard work. Plum Brook Station is about an hour away from Glenn. During the summer it was like an oven in the shop and certain parts are hard to come by. It’s been tough work, but I think the end goal is pretty well worth it.