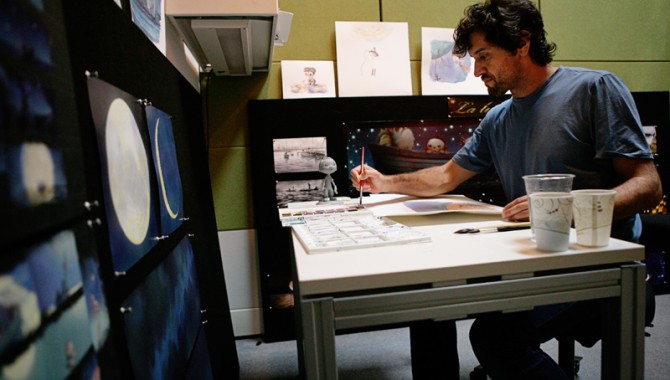

Enrico Casarosa, director of the Oscar-nominated Pixar short La Luna, painting in watercolor. Images courtesy of Pixar Animation Studios.

June 29, 2012 — Vol. 5, Issue 6

To get to “infinity and beyond,” sometimes you have to start at the moon.

One June 22, inside of dark, air-conditioned movie theaters across the country, a new short film premiered in front of Pixar’s latest release Brave. Called La Luna, this Oscar-nominated Pixar ‘short’ is the latest nugget-sized, computer-animated film to escort viewers into the world of computer animation. Usually enjoyed by moviegoers as comedic appetizers to the full-length film, Pixar’s shorts serve a critical behind-the-scenes role for developing its people, honing talent, incubating technology, testing out new ideas, and executing on a tight schedule and unglamorous budget.

The film, written and directed by Italian-born artist Enrico Casarosa, tells the story of a young boy’s introduction to his family’s unusual line of lunar work. Caught between the practices of his father and grandfather, the boy must navigate generational differences in order to find his footing in the family business. “La Luna is sort of this revisionist way, this fantastic way of seeing the moon and what it is to step on the moon,” explained Casarosa, who derived inspiration for the story from a compilation of works called Cosmicomics by author Italo Calvino. It is also a bit of a dark horse.

“It is something that is a little more slow-paced and poetic, something that makes you smile and think rather than just laughing,” said Casarosa. “It is different compared to what we’ve done in the past with the shorts.” Casarosa pitched the idea for the short to Pixar Executive Producer John Lasseter, who appreciated the personality of the story and gave Casarosa the green light to proceed.

Directing a Pixar short was a new experience for Casarosa. His decade-long career at the organization mostly involved working on larger, feature-length films like Ratatouille—not leading a team of his own on a yearlong project. “Until I pitched the short, I was really pretty much in story specifically,” explained Casarosa. “In directing you learn so much because you see much more of the whole production pipeline.“

Being in the director’s seat afforded Casarosa the experience of learning how to bring his vision for the story to life by interfacing with the film’s producer, Kevin Reher. “As the director, you could argue sometimes that you and the producers are the biggest allies and sometimes you’re the biggest enemies,” he said. “I think it needs to be that way. The producer is there to try and make sure you end on budget and walk away with something in your hands, not just an idea. It’s a struggle. The communication and the relationship are really important. I wanted to be very conscious of that. I didn’t want to be ‘the creative’ that doesn’t understand or wants to bend to the rules of the game.”

On a film, the producer is the one who assembles the A-Team: the right people for the right job at the right time. Similar to projects at NASA, expertise is a hot commodity and is usually funneled toward high-profile programs or projects. “You’re not the first in the pecking order to get a little help from some of the other departments,” said Casarosa. “You’re a small project…and sometimes it’s a real fight for someone to give us this person or that person, and get them at the right time. I have a huge appreciation for that [now]. It really is a big puzzle. When you’re in the middle of the trenches, I think it’s a lot harder to see.”

Throughout the project—long or short—developing, editing, and refining a story is a collaborative process. Screenings regularly bring in a full audience that is made up of anyone including the film crew, seasoned animators, or non-film staff. The culture is one where everyone can “chime in and give their notes about what works and what doesn’t,” explained Casarosa. “It doesn’t matter who you are, it matters what idea you have.”

During development, La Luna wrestled with several technical challenges that are often a result of working with a small budget, minimal research and development time, and accessibility to the latest and greatest tools. One of their biggest hurdles was something Pixar had yet to tackle in any of its films: facial hair.

“Computers don’t naturally do hair,” said Casarosa. “There are thousands of hairs and whether they do or don’t move isn’t easy to control. We’ve done a lot of that in the past with Monsters, Inc. with fur, but we specifically hadn’t done the kinds of mustaches and beards that we were looking for, which was something that needed to be animated with the talking.”

The Brave project team had a similar challenge (the movie features well-bearded and mustached Scotsmen), but they had the advantage of newer software that was more capable of addressing the facial hair challenge. “We didn’t [have the same tools] so we kind of had to tell it in our own way,” said Casarosa.

Casarosa initially thought including facial hair would save them money, eliminating the cost to model the mouth because it would be covered. They were wrong. “Usually the computer can just figure out how the hair would flow based on what it was attached to, but if we let whatever surface on their faces command the hair it would become this sort of crazy thing, which would move too much,” he laughed. “That was a real challenge for the longest time. The hair was just all over the place and their faces looked to be a little too alive.”

Close up of a model of the main character, a young boy, in the new Pixar short La Luna. Enrico Casarosa, director of the Oscar-nominated film, is painting using watercolor in the background.

Images courtesy of Pixar Animation Studios.

Casarosa was able to resolve the challenge by giving his animators the right amount of control over the shape of the facial hair. “That was a hard because we hadn’t done that before,” he said. “We had the limitation of our tools, but we tried to do something different with them.”

In a little over a year, La Luna was completed. Casarosa is now the head of story on an upcoming feature-length movie called The Good Dinosaur, which is expected to premier in 2014. As head of story, Casarosa is leading a team of artists as they draw out and sequence the visual aspects of the movie. Now leading a part of a larger production, he is aware of his role as a mentor. “You try and look for someone who is ready to step up and be the lead,” he observed. “So much of what we do as storyboard artists is about cinematography. It’s a lot about editing, and from this image you go to that image, and how it’s working or supporting our moment, our story. We really think quite minutely about all of those things. That’s where a lot is coming to fruition as far as trying to mentor, trying to give opportunities to grow the people around you.”

The small-team experience is valued at Pixar, explained Casarosa. It provides an opportunity for people to see a project throughout its entire lifecycle. “It’s really wonderful how that becomes a great learning experience for other people. Having smaller teams gives you this wonderful sort of camaraderie—everyone does a little bit more, and everyone is a little closer.”

Enrico Casarosa, director of the Oscar-nominated Pixar short La Luna, painting in watercolor.

Featured Photo Credit: Image courtesy of Pixar Animation Studios.