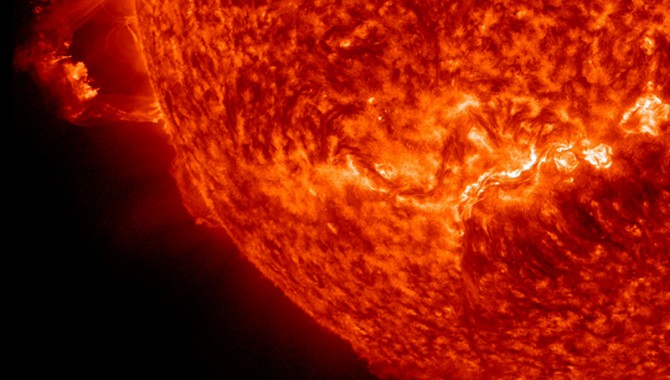

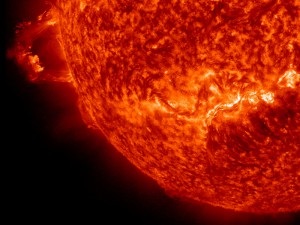

The Sun erupted with two prominence eruptions, one after the other over a four-hour period on Nov. 16, 2012. The action was captured in the 304 Angstrom wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light. It seems possible that the disruption to the Sun’s magnetic field might have triggered the second event since they were in relatively close proximity to each other. The expanding particle clouds heading into space do not appear to be Earth-directed. Photo Credit: NASA/SDO/Steele Hill

Vol. 5, Issue 11

Unlike physical elements, it is hard to guess the half-life of knowledge in advance.

The Sun erupted with two prominence eruptions, one after the other over a four-hour period on Nov. 16, 2012. The action was captured in the 304 Angstrom wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light. It seems possible that the disruption to the Sun’s magnetic field might have triggered the second event since they were in relatively close proximity to each other. The expanding particle clouds heading into space do not appear to be Earth-directed.

Photo Credit: NASA/SDO/Steele Hill

Pythagoras has had a pretty good run with his theorem for right triangles. Most knowledge does not endure the test of time, but a2+b2=c2 has been with us for about 2,500 years. Math is unique in this sense. Pythagoras did not need complex instruments to make measurements in order to arrive at his conclusion. Ancient physicists and astronomers were handicapped by the limits of what they could observe, and their work survives now primarily as a historical curiosity.

In the present, it can be difficult to gauge whether a new idea represents a significant breakthrough or a momentary blip, soon to be eclipsed by a greater development. This is true regardless of whether the knowledge in question is fundamental science, a new technology, or even a work process. Just as geometry is incomplete without Pythagoras, we cannot imagine modern manufacturing without Henry Ford’s assembly line, even if some of the workers are now robots.

The challenge of managing knowledge at NASA is that we do not know with any degree of certainty what will be useful to future practitioners. As I mentioned a few months ago, the team working on the Robotic Lunar Explorer Program at Ames Research Center looked back to the Surveyor and Ranger programs of the 1960s to develop a new lunar lander. They even translated Russian technical manuals for Lunokhod, a lunar rover from the same era.

We have an obligation to each other and to tomorrow’s practitioners to capture and share whatever we can, because we cannot anticipate the value someone else will find in our knowledge. Failures and mishaps serve as cautionary reminders of how little we understand at any point in time: “If only we had known.” We can forgive ourselves for failing to anticipate the unknown. Forgiveness is far more difficult when the refrain is: “If only we hadn’t forgotten.”