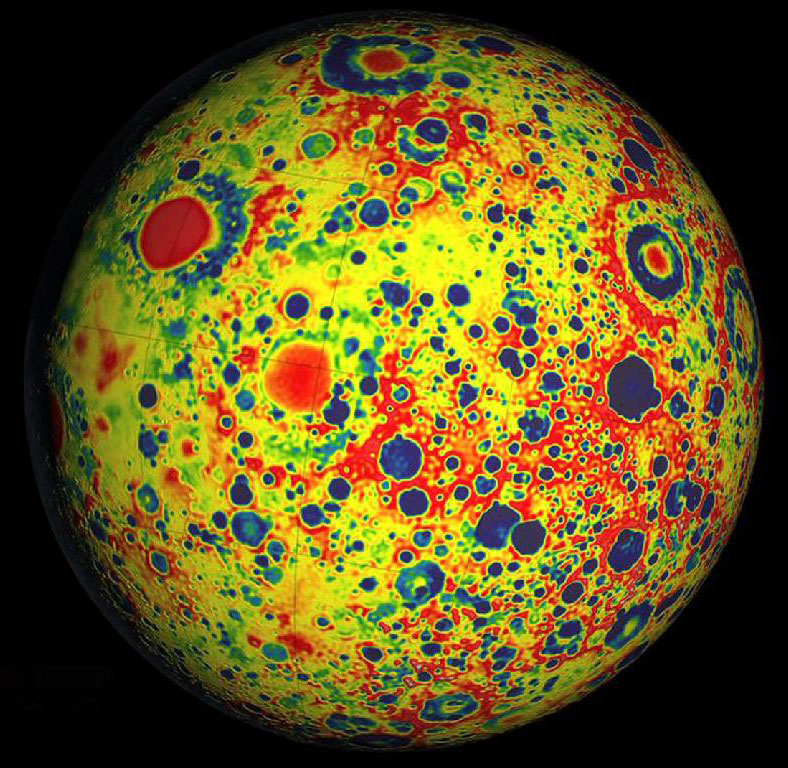

BLAST project team with their payload at McMurdo Station in Antarctica. Photo Credit: Mark Halpern

Vol. 5, Issue 12

How often do you need to wear sunglasses to do physics?

It is always a quest to design, develop, and launch a one-of-a-kind satellite to unlock a mystery of the universe. But not every project story is captured in real time on film. When Mark Devlin, Principal Investigator (PI) for the Balloon-borne Large Aperture Submillimeter Telescope (BLAST), set out on a quest with his team, his brother Paul Devlin, an award-winning documentary filmmaker, was there with a camera. The result is required viewing for anyone interested in an inside look at life on a small PI-led mission.

BLAST was designed to be set aloft in June 2005 from the European Space Range in Kiruna, Sweden and drift west for 5-9 days across the Arctic to Canada. As with many launches, this one began with waiting. Lots of waiting. The weather was terrible for weeks on end, forcing the team to sit around and fend off bouts of launch fever. Finally the clouds parted, and BLAST took off. On the fourth day of its flight, however, it picked up too much speed, leading to concerns that the payload would land in an inaccessible area. The flight operations team decided the mission should be curtailed, and it gave a command to cut the payload from the balloon. The data were largely unusable due to a problem with the telescope’s focus. Devlin and his colleague Barth Netterfield of the University of Toronto were determined to try again.

Eighteen months later, they were at McMurdo Station in Antarctica, ready for round two. As the ground crew prepared the balloon on the morning of the launch, Devlin reviewed a laundry list of problems that the project had avoided in the pre-launch period, saying, “I can’t think of anything that really went wrong so far.” The fun was just about to begin.

As the balloon inflated and the ground crew prepared to separate the payload from a mini-crane on the back of a flatbed truck, the line connecting the satellite to the balloon would not release. The payload began to swing like a pendulum, colliding with the back of the truck while the crew rushed to fix the problem. Finally the snag was resolved, and the balloon took flight.

The payload experienced a rough landing, and the satellite broke to pieces. The critical data were on hard drives encased in sturdy white plastic tubes, which were nearly invisible in the vast whiteness of Antarctica. On the last of a series of flyovers to search for the data, one of the team members spotted a break in the snow: it was the hard drives.

In addition to BLAST’s scientific findings, the project served as a training ground for a team of graduate students in astrophysics. The project team consisted of a skeleton crew of young scientists who learned what they needed to know from Devlin, Netterfield, and each other. “How do people learn how to be scientists?” Devlin asked rhetorically. “They’ve got to do it. They can’t just go to class. They’ve got to do it.”

Read more about the scientific findings from BLAST.