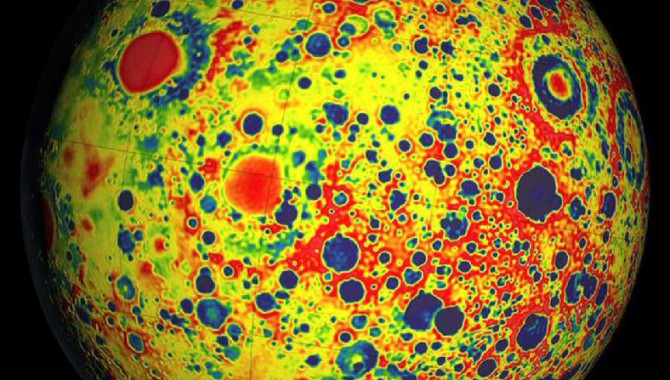

This image shows the variations in the lunar gravity field as measured by NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) during the primary mapping mission from March to May 2012. Very precise measurements between two spacecraft, named Ebb and Flow, were used to map gravity with high precision and high spatial resolution. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MIT/GSFC

Vol. 5, Issue 12

What is benchmarking and why do it anyway?

This image shows the variations in the lunar gravity field as measured by NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) during the primary mapping mission from March to May 2012. Very precise measurements between two spacecraft, named Ebb and Flow, were used to map gravity with high precision and high spatial resolution.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MIT/GSFC

At the time our organization became known as the Academy of Program/Project Leadership in 1995, there were few, if any, organizations like it in the world. We were a work in progress, a response to changes in the needs of the NASA workforce and the way project work gets done. Since then we have evolved in a number of areas, most notably in our emphases on supporting project teams and meeting the knowledge needs of practitioners. Throughout the decades, I have always valued the practice of looking at the work other project-based and knowledge organizations are doing. This practice of benchmarking—or establishing a standard by which others can be compared—has long been a way for the Academy and other organizations to ask: How do we measure up?

A critical part of determining how we measure up is getting unvarnished perspectives from people on the outside. Social scientists have demonstrated definitively that our self-perception is invariably biased; we are always subject to blind spots that may be obvious to others. In some cases, this inability to see ourselves can have tragic consequences. After the Challenger accident, sociologist Diane Vaughan coined the term the “normalization of deviance” to describe the process by which an organization adopts unhealthy behaviors and effectively makes them part of standard operating procedure.

Comparing ourselves to other organizations provides a reality check against that. At its best, it forces us to reexamine what we’re doing, and serves as an astringent that can wash away the “not-invented-here” mindset that is so common in organizations that execute one-of-a-kind complex projects.

Recently, I have engaged in benchmarking activities with Embraer, Shell, and the German Aerospace Agency (DLR). These meetings have made it clear that the pervasiveness of technology, the quantity of data available, and the common challenges we face in a difficult economic environment have created a great opportunity and challenge for all project and knowledge organizations.

There is a lot to be gained from studying the innovative solutions and best practices of other agencies. As former NASA Chief Safety Officer Bryan O’Connor said on the eve of his retirement from NASA, “I am not very good at inventing things or coming out of nowhere with creative ideas, but I know a good one when I see it, and I’ll steal it and benchmark and ask my guys to do something like it if we think it makes sense.”

There is more to benchmarking than stealing from the best: it is also about figuring out how to advance the state of the art to the next level. As David A. Whetten and Kim S. Cameron write, identifying a best practice “means learning from it and exceeding it. Planned performance goes beyond the best practice, otherwise benchmarking is merely mimicking.” 1

Smart organizations recognize that they do not have a monopoly on excellence, and take opportunities to learn from and share with others. Learning how other great organizations tackle their knowledge challenges is incredibly valuable as NASA matures in its approach to managing knowledge. There is a lot we can learn from organizations facing common challenges.

1 David A. Whetten and Kim S. Cameron, “Developing Management Skills,” p 556.