At a recent knowledge management conference, APPEL instructor Anthony Luscher discussed the value of case study-based learning for engineering design.

Luscher, an associate professor at The Ohio State University, was one of the speakers at the recent Knowledge 2020 2.0 conference hosted at Johnson Space Center (JSC) by NASA’s Chief Knowledge Officer. The conference brought together knowledge management experts from across the agency and private industry. APPEL News sat down with Luscher between conference sessions to learn more about his perspective on the role of case study-based learning at NASA—and the differences between teaching undergraduate engineers versus experienced NASA practitioners.

APPEL News: You created and taught an engineering design course for APPEL. Can you tell us about it?

Anthony Luscher: The course, Seven Axioms of Good Engineering (SAGE), grew out of the question: “What do engineers need to know?” Roger [Forsgren, APPEL Director] wanted to help NASA practitioners become better engineering designers. Since we’re both fans of history, especially the history of engineering and technology, we hit upon the notion that case studies would be a great way to learn. The seven engineering axioms tie together the case studies, which deal with different kinds of knowledge.

APPEL News: How does SAGE support engineers at NASA?

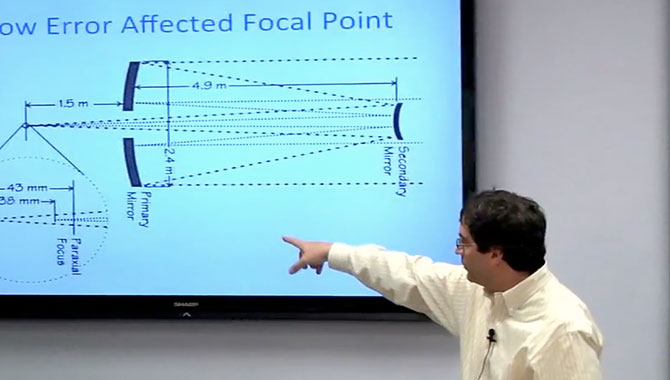

Luscher: It helps them make high-level strategic decisions in design. For example, one problem in engineering is people don’t understand why something was designed the way it was. If the design was successful, they want to copy it—without understanding the limitations of the design. Take suspension bridges. Early suspension bridges had many failures and the design principles were not well understood. One out of four bridges in the 1800s just fell down. Those English bridges were very flexible and they had very flat lines and no stiffening of the deck. Roebling, who designed the Brooklyn Bridge, was the first to realize that suspension bridges need to have a stiffened deck and the loads have to be distributed in a certain way. So that problem was solved. But in time, after the invention of cars, some engineers wanted to make bridges that looked like the early English bridges—they look nice, they’re very elegant. There were also economic issues in terms of doing more with lower cost and less material. That is how we got to suspension bridges that had dangerous vibrations and, in the case of the Tacoma Narrows, structural failure. People looked at the appealing shape but didn’t understand the engineering limitations. So several of the axioms we teach have to do with sharing archival knowledge—and understanding the limitations of knowledge.

APPEL News: Why did you think case study-based learning was the right approach to teach engineering design to NASA practitioners?

Luscher: Usually an engineer’s background is very equation oriented. SAGE asks them to think differently, to look at the bigger picture. The way we teach using case studies is we don’t give the answer away. Instead, we show them that learning can be like a motorcycle trip: getting there is most of the fun. So we bring out the answer through the class discussions because if I told them the answer, they wouldn’t get as much out of the learning experience. The case studies help them think more broadly about what they’re doing and why.

APPEL News: In your experience, do positive case studies—that is, cases with desired outcomes—make better teaching tools than negative ones, or vice versa?

Luscher: Both are effective, but mistakes that lead to catastrophic events are powerful learning tools. One thing engineers need to ask themselves is: Do they have a human understanding of the system they’re working on? A lot of classic failures come down to that. One case study we use in SAGE is Three Mile Island. At the time, commercial nuclear power was a young industry. The people working in it came out of the nuclear Navy. They were put in control rooms at these nuclear plants with new reactors, but they had no insight into how these reactors worked. So when something went wrong they didn’t know what to do. During the reactor crisis at Three Mile Island, an older guy came in and asked, “Have you tried closing the bypass valve?” He said it couldn’t hurt, it might help, and it would start giving them an understanding of what was going on. He was the only one who admitted to himself and others that they really didn’t know what was going on there. They didn’t have a human understanding of the system. So that’s a negative case study with a powerful lesson.

APPEL News: Speaking of lessons, what is the role of lessons learned in educating engineers? It’s someone else’s lesson, so how do people process that and benefit from it?

Luscher: They have to internalize it. Otherwise it doesn’t have value to them. I read about a situation where they put a satellite into space and the antenna didn’t fully open. They looked at the problem and realized the grease they’d used didn’t perform well in the vacuum of space. And the lesson learned was: Don’t use that grease in space applications. It’s simple, people can benefit from that lesson. But it isn’t something that makes them think more broadly. In SAGE, we’re addressing the bigger design issues. We’re trying to prevent the next big disaster by getting people to look at the bigger picture.

APPEL News: Case study-based learning has a story-telling aspect to it. Is story telling an important skill for an engineer?

Luscher: Most engineering case studies are not written by engineers. They’re written by writers or historians. A good writer will highlight what you need to know and fill in background information. A good writer talks about the big things and the small things. Reading the case studies helps engineers see that it’s not always enough to give a top-line report. The problem is engineers don’t always like to provide reasoning. So I encourage them to explain their reasoning to others in the class. That helps them strengthen their ability to communicate preferences with each other and to eventually create their own case studies. It helps them sell their views, their ideas. There’s a point where they will have to talk to someone else about their project—to get funding or for another reason. That’s when story telling can be a very important way of making your point.

APPEL News: You teach students at The Ohio State University as well as NASA practitioners through APPEL. Is there a big difference between teaching university engineering students and NASA engineers?

Luscher: Yes. In particular, I think that case study-based learning is more appreciated after a person has been out in the industry, designed some things, and managed a project. That way they can understand the subtleties of the cases. Because a lot of the cases are about classic interactions: man versus man and man versus nature. If they’ve never designed real things, managed real projects, it all looks easy. But once they have done those things, they know the issues and better understand the nuances of the cases. So I think case study-based learning is better for people who are already out in the working world. They get more out of it.

APPEL News: Before you go—what areas of an engineer’s education may need development after they graduate from college in order to be effective in the workforce?

Luscher: I don’t think undergraduates get enough understanding of the people side of design. They immediately think they know the customer and often are unwilling to actually talk to the customer. But how can you do good design if you don’t know what your customer wants? Design and the user experience are linked. You need to know how people will use the thing you’re developing before you even start designing. And the customer can’t always verbalize what they want. Most undergrads don’t really get that.

Learn more about the APPEL course Seven Axioms of Good Engineering.

Read Seven Axioms of Good Engineering: Development of a Case Study-Based Course for NASA.