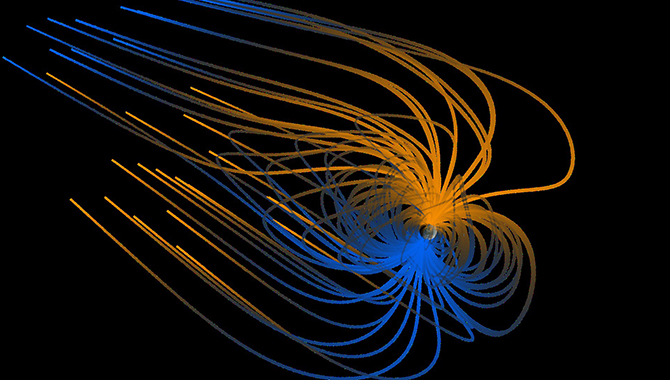

Stereoscopic visualization depicting a simple model of Earth’s magnetic field, which helps shield the planet from solar particles. Solar wind stretches the field back, away from the sun.

Image Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio

Recently, a NASA mission encouraged musicians to look to space as inspiration for creative expression. This isn’t the first time a composer has turned NASA findings into art.

As the Juno mission prepared for insertion into orbit around Jupiter, NASA announced a collaboration with Apple designed to stimulate synergies between musical composition and interplanetary exploration. Highlights of the collaboration, which inspired several pieces of music, are on view in the documentary “Destination: Juno.” The video includes commentary by Juno principal investigator Scot Bolton and can be accessed via iTunes.

This initiative is reminiscent of an earlier piece of music that was also inspired by NASA’s work. Nearly half a century ago, composer Charles Dodge was looking for a new project after completing his doctorate in musical arts. He found it in the form of data notating interactions between solar wind and the magnetic field surrounding the earth. In the resulting piece of music, Earth’s Magnetic Field, Dodge leveraged an intersection between physics, computer programming, and artistic creativity to conceive a novel composition that the New York Times called one of the “ten most significant works of the 1970s.” APPEL News sat down with Dodge to find out what inspired him to use skills traditionally associated with STEM [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics] fields to inform his art in the 1960s and 1970s, and what advice he might have for musicians hoping to do the same today.

APPEL News: In 1970, you were a professor of music at Columbia University. How did you end up composing a piece of music based on NASA data?

Charles Dodge: I had just finished my doctorate, and my dissertation involved using computers to synthesize sound. That is, using computer software to realize in sound a composition I’d written. At the same time, there was a small group of scientists at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies—which was on 112th and Broadway, not far from my office at Columbia—who had a scientific notation depicting fluctuations in the magnetic field surrounding the earth that was caused by solar wind. The notation they had was something called a “Bartels’ musical diagram.” Julius Bartels was a German geophysicist who came up with a way of mapping the effect of solar wave and particle radiation on Earth’s magnetic field using a Kp index. In order to present the information clearly, he wrote out the data in a way that looked very much like musical notation or a “musical diagram.”

APPEL News: Did this “musical diagram” actually depict musical notes? Or did it convey scientific data?

Dodge: Scientific data. But because the data are presented in a way that looks like a musical score, these scientists at Goddard—Bruce Boller, Stephen G. Ungar, and Carl Frederick—wanted to find a way to listen to the Bartels’ musical diagram of the magnetic field. So they contacted the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center to find someone who could help them with this. The Electronic Music Center said they couldn’t help because the scientists had a digital representation of the notation, and the Music Center didn’t deal with computers—their work was strictly analog. However, they told the scientists that there was this guy in the music department at Columbia who used computers to synthesize sound, and suggested they get in touch with him.

APPEL News: And that person was you?

Dodge: It was. As I remember, I met with them on a Saturday. The scientists were PhDs, a couple of them were geophysicists, all roughly my age. Ungar was a real computer whiz, and once he found out what format I needed the data in to make music, he reformatted the Bartels’ musical diagram in a way that they could be read by a computer sound synthesis program.

Once I got the reformatted data, I did some musical experiments at Columbia. The result had sort of a nice tune to it, nothing special. I took the digital recording that I’d created out to Bell Telephone Laboratories, whose facilities I used to create my music, and put it on analog tape so we could hear it. At the time, remember, very few places had the means to listen to digital recordings.

Shortly after that, one of the NASA scientists—and I don’t know who it was because I wasn’t there—played the tape at a party. Someone at that party had a connection to Nonesuch Records, and suggested to the record company that they might be interested in doing something with the recording, with this “solar wind music.” Incidentally, at the time I was already producing a record for Nonesuch: I was one of three composers featured on an LP called Computer Music. So Nonesuch knew my music and knew about the scientists from NASA and heard the experiment I’d put on tape, and they got excited and commissioned me to do a whole LP of “solar wind music.”

APPEL News: How did you turn the NASA data into a musical composition?

Dodge: The data was simply a sequence of numbers depicting variations in solar wind and the changes those variations produced on Earth’s magnetic field. Specifically, it represented an average of the readings of the solar wind variations, over a three-hour period, from roughly a dozen geophysical monitoring stations throughout the globe. For the piece, I used eight readings per day for an entire year: January 1 through December 31, 1961. Those eight readings multiplied by the 365 days in the year became the musical notes.

The question was how to interpret the numbers sonically—and do it in a way that was musically interesting. So the piece needed some musical structure. Fortunately, there were patterns in the data that I could work with. First, I set up a correlation between the level of the Kp readings and the pitch of the notes. Then I worked with tempo. In the piece, there are two different ways of marking time. In one of them, the time changes continuously: the notes speed up and slow down. The other way has a more even tempo. I wrote a computer program, a simple one, that would take two data readings, if the same, and map them as one note, then look for the next double reading. I also used another feature of the data, which was called “sudden commencements.” These were rapid changes in Earth’s magnetic field. There were a number of these during the year, so I used them to musically define sections of the piece.

I also thought my job was not only to structure the temporal aspect of the piece but to try to invent a sound image of the planet’s magnetic field that sounded in some sense “radiant.” In other words, to have the musical sound reflect the solar/magnetic field phenomenon.

APPEL News: To get the sound and structure you wanted, you wrote your own computer program?

Dodge: Yes. Max Mathews and others at Bell Labs had already figured out how to synthesize sound with a digital computer. Mathews had actually created a computer language, I guess you could call it, that people could use to express their musical ideas. So I didn’t have to write that code, but I had to write computer programs that fit into this broader program, this meta-program.

APPEL News: Yet you got your undergrad degree—and did your graduate work as well—in musical composition. How did you cross over from the “artistic” side to the “technology” side to create this piece? Did you already have computer skills or a mathematics background?

Dodge: I never had them in any great abundance, but I developed enough to learn how to use those programs. You needed some computer chops, but what you really needed was an understanding of acoustics. You needed to know the physics of sound. And I had studied that as an undergraduate at the University of Iowa. Not exhaustively, but I’d taken a course in musical acoustics, and then I’d read extensively in that field when I came to New York for graduate work. There was a Frenchman at Bell Labs, a composer named Jean-Claude Risset, who furthered the understanding of musical acoustics. He was working there in the sixties. He helped me, and I learned a lot from him about effective ways of using the computer to synthesize sound.

APPEL News: After you wrote Earth’s Magnetic Field, you went on to use computer technology for your next piece as well: a series of compositions called Speech Songs. Did you use the same kind of computer program as for Earth’s Magnetic Field, or did you do something different?

Dodge: That was quite different. For Speech Songs, I took advantage of the speech research that I would hear at Bell Labs when I went out there to work on Earth’s Magnetic Field. The odd thing about that piece, Earth’s Magnetic Field, was that I could work on it at Columbia’s computer center, but I couldn’t hear what I was doing. I would have to take the digital tapes I made at the computer center out to Bell Labs and convert them to analog on their system so I could hear the music. Then, when I heard them, I would get some idea of where to take the composition next. Today, every computer in the world has a digital-to-analog converter, but in those days there were very few available for musical use. At Bell Labs, the converter was in the speech research department. So I would hear, when I walked down the long hallway to the digital-to-analog converter, speech experiments going on in the laboratories off either side of the corridor.

I’d been interested in using the computer to synthesize voice for a long time. In 1971, the year after Earth’s Magnetic Field, I talked with Max Mathews about coming to study speech in his department, which was the Bell Labs Acoustic and Behavioral Research Center. Mathews was an amazing guy. As I said before, he had created the computer music program that I used as the basis for the program I wrote to create Earth’s Magnetic Field. Max’s boss, by the way, was John Pierce, who posited that you could establish communications by bouncing signals off of a satellite. This led to Project Echo, which was a great success, and involved both NASA and Bell Telephone. Pierce also had an interest in music.

So I studied speech in Mathews’ department at Bell Labs. And there was a physicist named Joseph Olive, a member of the department, who was the brother-in-law of a composer I knew and was very interested in music himself. He invited me to use the systems, which he’d developed to analyze and synthesize speech. That was instrumental in developing Speech Songs.

APPEL News: It sounds like some of the scientists and engineers you worked alongside as you explored technology to develop your music served almost as mentors. Is that true?

Dodge: Definitely. I was really lucky; I had some very generous mentors. Max Mathews, of course. And Godfrey Winham at Princeton. I spent a year studying computer music there. Also the head of the Columbia University Computer Center, Kenneth King: he was so generous in letting me use the computer at the university. King had a PhD in physics. In that generation, people thought computers were neat things that could do stuff that nobody imagined. So they encouraged people like me to pursue that—to see what the computer could be made to do in a new field.

APPEL News: What was it about their work, or about technology in general, that sparked your artistic creativity?

Dodge: The late 1960s and early 1970s was a time of great optimism about technology. I can remember reading in the New York Times about chips and how it would be possible to store so many computer instructions in a thing the size of your fingernail—yet the computers we were using at that time were as big as boxcars. It was very inspiring to consider what was already possible, and what would be possible next.

Also, I needed the computer as my instrument, my performer. Back then, I wanted to be a composer. I’d written quite a bit of music. I was living in New York, which was full of some of the greatest performers in the world—but they weren’t usually available to perform music by untested and obscure young composers who had no money. And so the computer was a way of continuing to develop as a composer by realizing in sound some of my musical ideas.

APPEL News: Finally, do you have any advice for composers who are inspired by NASA’s missions today?

Dodge: I would encourage them to keep in mind that the sources of inspiration for composition can come from a wide range of places. NASA’s work is one of the exciting things in our age, and as such it would certainly seem to me to be a way of inspiring creative thinking, just as it was for me in the 1960s and 1970s.

___

Charles Dodge is an American composer best known for using synthesized sound and voice, fractal geometry, and a combination of computer music and live performers in his work. Dodge received his B.A. from the University of Iowa and his M.A. and PhD from Columbia University before founding the Center for Computer Music at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York. He co-authored Computer Music: Synthesis, Composition, and Performance and later taught music at Dartmouth College.