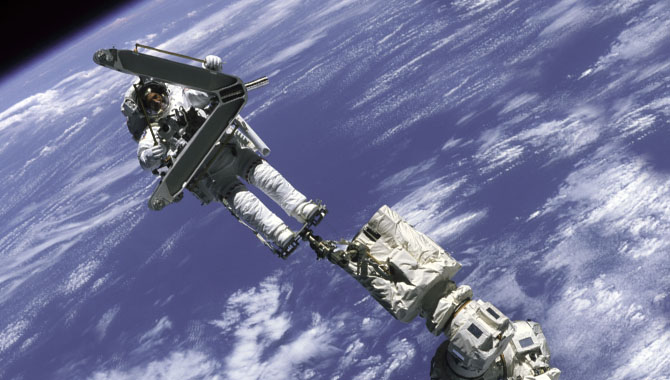

Crew member Lee M. E. Morin participated in his first extravehicular activity (EVA) during STS-110. Here, he is anchored to the station’s robotic arm, Canadarm2, which was used for the first time to move astronauts during EVAs.

Photo Credit: NASA

Fifteen years ago, the space shuttle Atlantis blasted off from Kennedy Space Center to deliver and install the S-Zero (S0) truss: the backbone of the International Space Station (ISS).

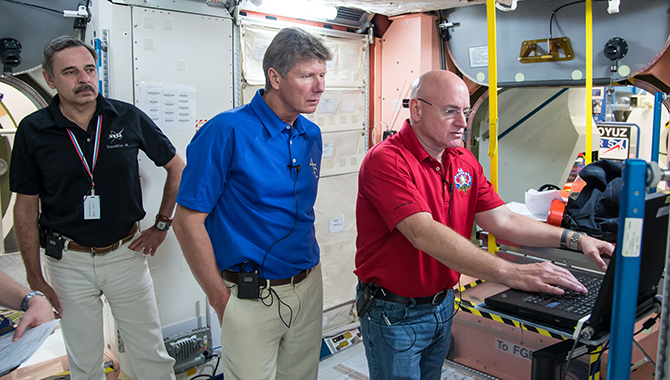

Astronauts Daniel W. Bursch (left), Expedition Four flight engineer, and Morin, STS-110 mission specialist, move equipment in the Destiny laboratory on the International Space Station (ISS). Astronaut Jerry L. Ross, STS-110 mission specialist, is visible in the background.

Photo Credit: NASA

Construction of the ISS began in November 1998 with the launch of the Zarya module, which became the cornerstone of the station. Over the next 14 years, more than a dozen additional assembly missions contributed to the development of the ISS. Then, on April 8, 2002, NASA launched the 25th flight of the Atlantis, which headed for low Earth orbit (LEO) carrying key components to enable expansion of the station.

The main goal of the STS-110 mission—also known as ISS Assembly Mission 8A—was to deliver and install the S0 truss. This 43-foot, 13-ton segment, called the Center Integrated Truss Structure, served as the core of the station’s truss framework. It was installed on top of the Destiny module, the primary U.S. orbital research facility, and connected to the overall structure with four module-to-truss structure (MTS) struts. The S0 was the first of nine segments that would ultimately support power and cooling systems for future research facilities on orbit, enabling the ISS to achieve its scientific goals.

STS-110 carried another crucial component: the 1,950-pound aluminum-titanium Mobile Transporter (MT). Together with the Mobile Base System (MBS), which was installed during STS-111, the MT formed the Mobile Servicing System: the first on-orbit railroad. To remain on track in microgravity, the MT relied on wheels both above and below the rails so that it could cling to the structure like a suspension roller coaster. The track, which eventually stretched 278 feet long, ran outside the ISS and could be operated by ground controllers or crew on station. Essentially a work platform on wheels, the Mobile Servicing System was designed to whisk the station’s robotic arm, called the Canadarm2, along the entire length of the ISS’s truss structure. This made it much easier to transport large payloads around the station, which was imperative for completing the on-orbit complex as well as for future work.

Given its diverse goals, STS-110 was one of the most complex ISS assembly missions. The crew spent a week on station working with the Expedition Four astronauts to complete the work. Installation of the S0 and MT required four extravehicular activities (EVAs) as well as help from both the Canadarm2 and the shuttle’s robotic arm.

The mission ended on April 19 after nearly 11 days in flight—but not before earning its place in NASA history by marking a number of “firsts” for the shuttle and space station programs. In addition to installing the first railroad in space, STS-110 was the first mission to use the station’s robotic arm to move crew during EVAs. It was also the first time that all shuttle EVAs were conducted out of the station’s airlock. The crew set several records as well. Mission Specialist Jerry Ross became the first person launched into space seven times and, after completing his two EVAs for STS-110, the first to conduct nine spacewalks. He also set a record for the greatest amount of time spent on EVAs: 58 hours and 18 minutes. His fellow crewman Steve Smith wasn’t far behind, coming in second on the record for number of EVAs (seven in total) and duration of spacewalks: 49 hours and 48 minutes. Finally, the Atlantis had a “first,” too: STS-110 was the first time a shuttle used three Block II Main Engines, which enhanced safety, reliability, and flight capacity.

Today, the ISS is a state-of-the-art facility for scientific exploration across a range of disciplines. Part of the U.S. section is a National Laboratory, enabling research for non-NASA federal agencies, private industry, and academia. The rest of the facility remains a key resource for agency research, including investigations into issues impacting human spaceflight as part of NASA’s journey to Mars. All of this is made possible, in part, by the success of STS-110.

Learn more about STS-110 in this interactive video (requires Flash Player).

Read an APPEL News article about the 15th anniversary of uninterrupted human habitation of the ISS.

Watch a video about the extraordinary accomplishment of constructing the ISS.