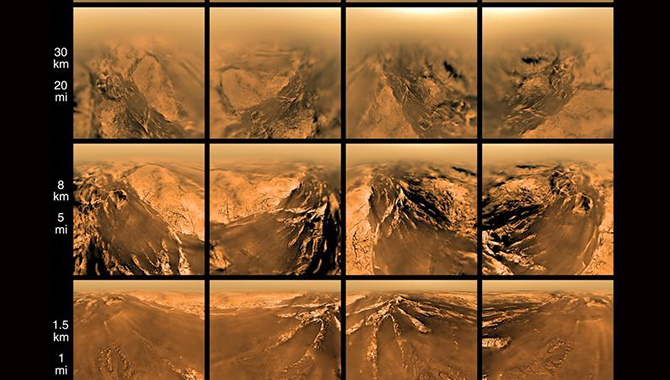

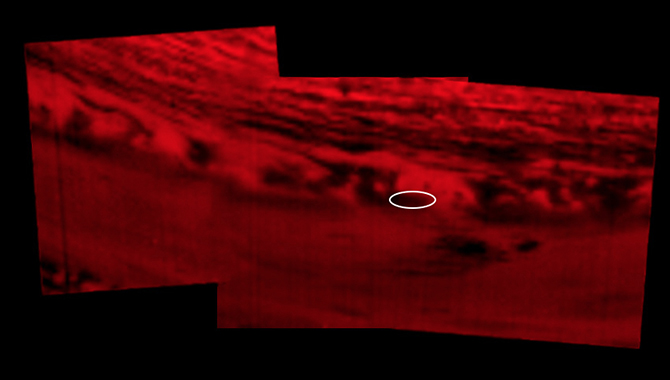

This montage of infrared images shows approximately where Cassini entered Saturn’s atmosphere to end its mission on September 15, 2017.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

On September 15, Cassini’s 13-year odyssey through the Saturn system—which transformed views on the possibility of life beyond Earth—came to a grand finale.

“There are times in this world when things just line up,” said Cassini program manager Earl Maize, shortly after the spacecraft ended its mission by plunging into the atmosphere of Saturn. “[W]e can…say the same thing about the Cassini mission. A superb machine in an amazing place doing everything we could possibly do to reveal the mysteries and secrets of our solar system.”

Cassini was conceived in response to interest in Saturn after the Voyager spacecraft flew past the gas giant in the early 1980s. Ultimately, three space agencies, 17 member nations, hundreds of contractors, and thousands of engineers, scientists, and support staff worked together to make the mission possible.

On October 15, 1997, Cassini left Cape Canaveral Air Force Base carrying the ESA (European Space Agency) Huygens probe, which was destined for Saturn’s moon Titan. The spacecraft arrived at its destination seven years later, on June 30, 2004. With its suite of 12 science instruments, Cassini was exceptionally well equipped to investigate the Saturn system. For 13 years, that’s exactly what it did, orbiting the planet and exploring its moons and rings.

Perhaps its most extraordinary findings concerned the potential for life beyond Earth. Together and apart, Cassini and Huygens explored Saturn’s largest moon, which is bigger than the planet Mercury. They conducted a joint flyby on December 13, 2004, and then Cassini released the probe at Titan on December 24. Using radar from Cassini and direct sampling via Huygens, scientists determined that the moon is the only body in the solar system other than Earth that has liquid on its surface and the only satellite in the solar system with a substantial atmosphere. They found that Titan’s seas consist of methane, which dashed hopes that the moon might support life forms similar to those found on Earth. Nonetheless, some scientists hypothesize it might possess the chemical foundation to develop non-water-based life forms.

Cassini went on to explore the small moon Enceladus. The satellite, which is the most reflective object in the solar system, was assumed to be frozen solid. It came as an enormous surprise when Cassini’s composite infrared spectrometer (CIRS) found that the moon’s south polar region is unexpectedly warm. Images from Cassini revealed that Enceladus emits plumes of ice and water vapor from its southern hemisphere, suggesting the presence of a subsurface ocean. The team used the Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) to sample the content of the plumes, which revealed the presence of organic compounds that could support microbial life beyond Earth.

“I think one of the biggest legacies from Cassini will be the fact that we now know that there are ocean worlds not only around Jupiter but also around Saturn. We have Enceladus, Titan, perhaps Dione—sort of opening up our view of where could we find life in our solar system. Maybe it doesn’t have to be in that narrow zone, the Goldilocks zone where the earth is, but could be elsewhere,” said Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker.

Cassini’s original mission, completed in 2008, was followed by two extensions: the Equinox Mission and the Solstice Mission. Planners had Saturn’s ocean worlds in mind as they plotted a finale for the spacecraft that would maximize science opportunities while negating any danger of contaminating Saturn’s moons. With propellant running out, the team had to choose between sending the spacecraft out of the Saturn system to explore elsewhere—Jupiter and Uranus were both suggested—or keeping it where it was. Ultimately, the team decided that the greatest scientific value would be in continuing to investigate Saturn. That choice dictated that the spacecraft had to be destroyed.

“There are international treaties that require us not to leave an untended spacecraft in the inner system where it might inadvertently collide with Enceladus—which we know is just rife with all of the materials for life—Titan, or other any of the other icy satellites,” said Maize. “So seven years ago we began a mission that planned to use every last kilogram of our propellant and finish up exactly the way we did.”

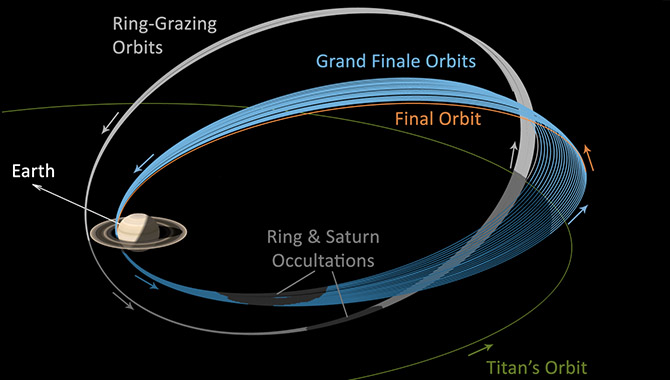

The mission design featured a “grand finale”: 22 proximal orbits in which the spacecraft flew between Saturn and its rings, using gravity assists from Titan to shift the orbits in order to obtain as many new views of the planet as possible. Cassini leveraged eight of its 12 instruments to collect data until the very end. It measured Saturn’s gravitational and magnetic fields, assessed the mass of the planet’s rings, and directly sampled its atmosphere and ionosphere.

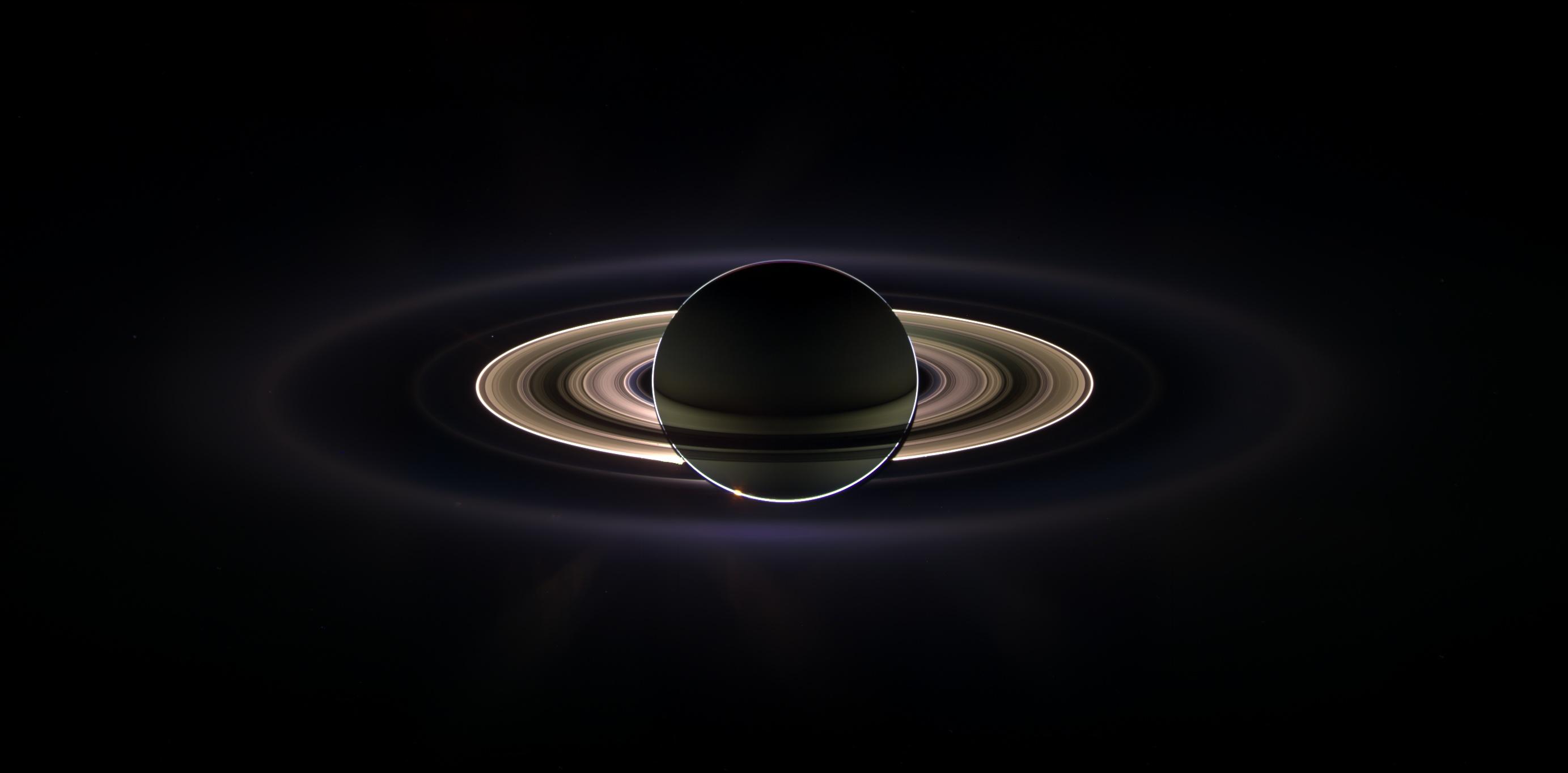

The spacecraft remained in excellent working order throughout its 20-year journey. It logged 4.9 billion miles, performed 293 orbits, collected nearly half a million images, and sent back 635 gigabytes of data. In its final moments, the spacecraft transformed into the first Saturn probe, returning data until it succumbed to the planet’s atmosphere.

“Cassini as a spacecraft could have gone on a long time, but it accomplished its mission at Saturn,” said spacecraft operations manager Julie Webster. “When they designed it, they took all the lessons learned from the Voyagers and the Galileos and the Magellans and Mars Observer, and built a perfect spacecraft. Right to the last end, the whole electronic system of the spacecraft ran at room temperature. That’s an amazing accomplishment. And that speaks to all the individual engineers that built this spacecraft to last, [and] the mission planning team and navigation team that designed a trajectory to get the best bang for the buck for the scientists.”

Although its mission is over, Cassini leaves behind an enduring legacy.

“The discoveries that Cassini has made over the past 13 years in orbit have rewritten the textbooks of Saturn, have discovered worlds that could be habitable, and have guaranteed that we will return to that ringed world,” said Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) director Michael Watkins.

That sentiment was echoed by Jim Green, director of Planetary Science in the Science Mission Directorate (SMD) at NASA. He noted that the agency is currently running a competition for future New Frontiers missions. “And in that call for proposals, we included Enceladus and Titan,” he confirmed.

In addition, the upcoming Europa Clipper mission will incorporate lessons learned from Cassini. Cassini’s mission planners leveraged gravity assists from Titan to shape the spacecraft’s orbits around Saturn in order to continually explore new aspects of the planet and its surroundings. The Europa Clipper team plans to use the same idea as their spacecraft orbits Jupiter in order to study its moon Europa, another ocean world that may harbor the potential for life.

The Cassini-Huygens mission was a cooperative project of NASA, ESA, and the Italian Space Agency. Cassini was designed and assembled by JPL, which managed the spacecraft for the SMD.

Watch a video showing Cassini’s last looks at Saturn before it plunged into the planet’s atmosphere.

Download The Saturn System Through the Eyes of Cassini, a free NASA eBook featuring some of the most spectacular images captured during the mission.

Read an APPEL News article about Cassini’s discoveries within the Saturn system.

Learn about the challenges faced during the Cassini-Huygens mission in this APPEL News article.