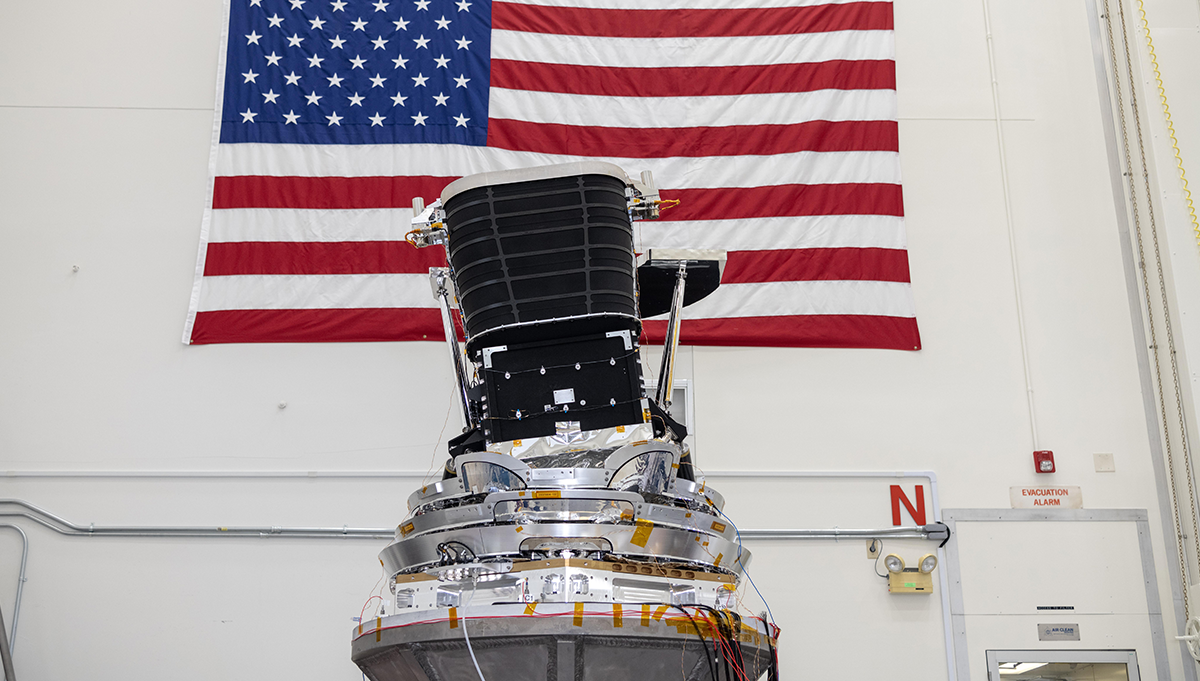

NASA’s SPHEREx observatory, shown here in a clean room after environmental testing at BAE Systems in Boulder, Colorado, in late 2024, launched on March 11, 2025. The team is preparing the telescope to begin gathering sweeping data that could help answer fundamental questions about the history of the Universe. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/BAE Systems

Compact infrared telescope will look for evidence of cosmic inflation and ice in the Milky Way.

When early humans looked into the night sky, they saw a luminescent band of faint light and ethereal darkness stretching across the heavens. In myths, many cultures interpreted the wondrous sight as a supernatural road or a river in the sky. It wasn’t until the late 1700s that astronomers began to understand that this “road”—the Milky Way—was actually a vast disk of stars. And not until the 1920s did Edwin Hubble’s work reveal that it was merely one galaxy among many.

Today, cosmologists estimate there may be as many as two trillion galaxies in the observable universe. And although observations from sophisticated space telescopes have answered many questions about the Universe, they have raised new ones. For instance, why, on the largest scales, does the universe appear uniform, with matter and radiation distributed evenly in all directions? Why do measurements indicate that space-time is nearly flat?

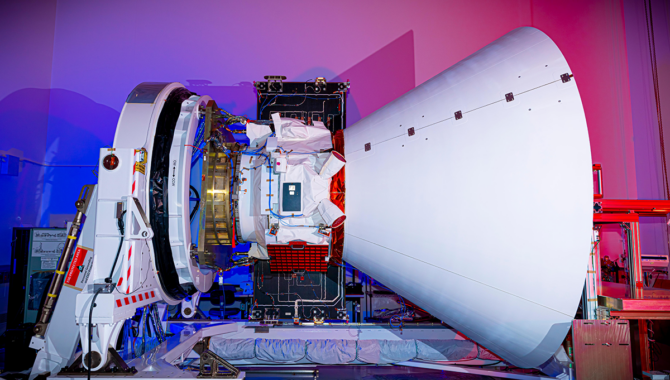

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, carrying NASA’s SPHEREx observatory and PUNCH (Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere) satellites, launches on Tuesday, March 11, 2025. Credit: SpaceX

On March 11, 2025, NASA launched an astrophysics observatory, SPHEREx, that will enable scientists to seek answers to these and other fundamental questions about the Universe. SPHEREx will operate in low earth orbit and use a technology known as linear variable filter spectroscopy to produce 102 maps in 102 wavelengths of infrared light every six months, over a two-year primary mission.

Short for Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer, SPHEREx is about 8.5 feet high and about 10.5 feet wide. It will operate in a low Earth, Sun-synchronous orbit. The compact infrared telescope, with an 8-inch primary mirror, is surrounded by a series of three concentric photon shields that protect the sensitive instrument from the light and heat of both Earth and the Sun. Each of the shields comprises an aluminum honeycomb structure sandwiched between two thin sheets of aluminum. Beneath the shields is a V-groove radiator, designed to keep the telescope at a constant -350 degrees Fahrenheit.

“How does the Universe work? How did we get here within that Universe? And are we alone in that Universe? Now, those questions, they’re big enough where we can’t answer them with one instrument. We can’t even answer them with one mission. We need a full fleet to do that,” said Shawn Domagal-Goldman, Acting Astrophysics Division Director, speaking at a recent NASA press conference.

While the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope function like zoom lens—capturing fine details of specific cosmic objects—SPHEREx will scan the full sky. This broad, panoramic perspective provides astronomers with an unprecedented view of the Universe, revealing as many as 450 million galaxies and other celestial structures, as well as clues to how they developed billions of years ago.

“It’s going to get reverberations from the Big Bang, in fact, fractions of a second after the Big Bang that echoed into the eras that SPHEREx is going to directly observe.””

It will not only enable astronomers to trace the evolution of galaxies but could also offer them insight into a spectacular moment.

“If you can imagine an explosion happening and all the little bits and pieces flying out from it, if you get really good information, you might get some information about that explosion that happened at the center,” Domagal-Goldman explained. “SPHEREx is going to do that too. It’s going to get reverberations from the Big Bang, in fact, fractions of a second after the Big Bang that echoed into the eras that SPHEREx is going to directly observe.”

These fractions of a second about 13.8 billion years ago are known as cosmic inflation, a theory first advanced in 1980 by physicist and cosmologist Alan Guth, now a professor of physics at MIT, and further developed by colleagues Andrei Linde at Stanford University and Alexei Starobinsky at the Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics. According to the theory, for an infinitesimal fraction of a second, when the observable Universe was smaller than an atom, it began expanding faster than the speed of light, growing by a factor of 100 trillion trillions.

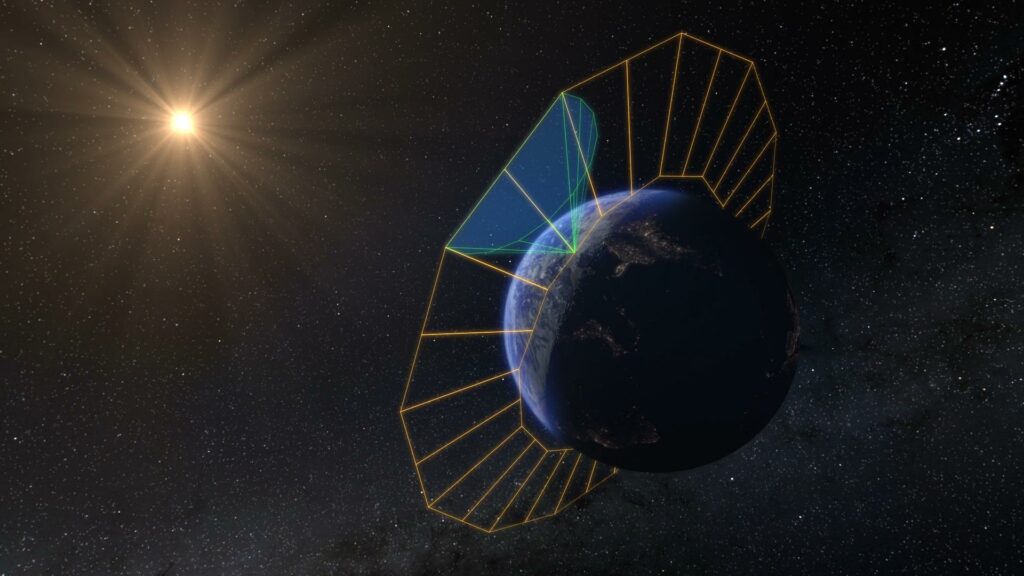

This artist’s concept depicts the spacecraft’s orbital plane in orange, and its field of view in green. Each of the telescope’s orbits allows it to image a 360-degree strip of the celestial sky. As Earth’s orbit around the Sun progresses, that strip slowly advances, enabling SPHEREx to complete four all-sky maps in two years.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

“A theory like inflation is actually needed to explain lots of the observations we have, particularly from the cosmic microwave background, because it answers questions such as why is the Universe uniform on the largest scales and why is this geometry spatially flat?” said Phil Korngut, an Experimental Astrophysicist who is the SPHEREx Instrument Scientist.

“If we can produce a map of what the Universe looks like today and understand that structure, we can tie it back to those original moments just after the Big Bang. So, the largest scales imaginable—billions of light years across—are tied to the smallest scales imaginable, just the tiny fraction of an atom,” Korngut said.

Closer to home, SPHEREx will survey the cold, dense molecular clouds of gas and dust in the Milky Way where stars and planets form. Because molecules such as water, carbon dioxide, and methane absorb infrared light at specific wavelengths, spectroscopy can capture these “fingerprints” in the spectrum.

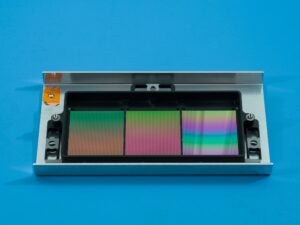

NASA’s SPHEREx mission will use these filters to conduct spectroscopy, a technique that lets scientists measure individual wavelengths of light from a source, which can reveal information such as the chemical composition of the object or how far away it is.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

“Let’s start with one of the biggest questions we have about our universe: Where is all the water? On Earth, we know that every living creature needs water to survive. But how and when did that water get here? And how might that work for planets around other stars?” said Rachel L. Akeson, a senior research scientist at Caltech’s IPAC and the task lead for the SPHEREx Science Data Center.

“We think that most of the water and ice in the Universe is in [molecular clouds]. It’s also likely that the water in Earth’s oceans originated in a molecular cloud. SPHEREx will look for spectral fingerprints like dark notches in the light from millions of stars within our galaxy. This will include stars that have only just been born and those are hiding behind the dark molecular clouds where stars are created together,” Akeson said.

After an approximately one-month checkout period, when engineers and scientists will calibrate the instruments, cool the telescope to its operating temperature, and characterize its optical performance in space, the SPHEREx team will begin a two-year primary mission.

The observatory will begin its two-year prime mission after a roughly one-month checkout period, when engineers and scientists will test the spacecraft’s systems. The SPHEREx mission is managed by NASA JPL for the agency’s Astrophysics Division within the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters. BAE Systems (formerly Ball Aerospace) built the telescope and the spacecraft bus. The science analysis of the SPHEREx data will be conducted by a team of scientists located at 10 institutions in the U.S., two in South Korea, and one in Taiwan.