Taralyn Frasqueri-Molina is a project manager at the Walt Disney Animation Studios in Burbank, California. Photo courtesy of Taralyn Frasqueri-Molina.

June 14, 2011 Vol. 4, Issue 4

At the request of her manager, Taralyn Frasqueri-Molina opened the first page of the PMBOK™, holding a highlighter and pencil. She was going to change how her group did work.

Taralyn Frasqueri-Molina, or “TL” as she is often called, is a young project manager at the Walt Disney Animation Studios in Burbank, California. She oversees media technology projects that shape and optimize work environments for Disney animators. Ask her about project management today and she’ll explain its importance in a way that takes you on an adventure. Five years ago, she might have given you a blank stare.

Taralyn Frasqueri-Molina is a project manager at the Walt Disney Animation Studios in Burbank, California.

Photo courtesy of Taralyn Frasqueri-Molina.

When she arrived at Disney in 2005, the Media Engineering Department was fun, but disorganized. Schedules slipped and costs increased. Her manager, Ron Gillen, was almost a year into his new position and determined to fix the problem. He asked Frasqueri-Molina to “tame the chaos” of the scheduling department. As lead of the two-person scheduling crew, she reshaped the process so rooms were no longer double-booked, equipment showed up when it was supposed to, and support crew was available as needed. Frasqueri-Molina succeeded to the point where she engineered herself out of the job.

But even with scheduling on track, it didn’t seem to fix the department’s problem.

Gillen gave her a new job: media resource supervisor. If the problem wasn’t the scheduling, perhaps it was the people and the equipment. She managed the distribution of media equipment (televisions, microphones, and other audiovisual gear) and the people responsible for setting it up. The staff seemed to work well. Yet, even with things going smoothly, the department’s problems still persisted.

“We had these initiatives that had a specific start and end date, and we couldn’t seem to get them done,” said Frasqueri-Molina. This led her group to conclude that a lack of project focus might be the heart of their problem. Gillen approached Frasqueri-Molina a third time. “I hand you something and you seem to fix it. I hand you something else and you seem to fix it. So here’s the PMBOK™. Fix it,” Frasqueri-Molina recalled him saying.

“It was the end of 2006 when he handed me this big, strange book with words I’d never heard before,” she said. It was the Project Management Institute’s Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK™). She read each line of the 450 or so pages of the PMBOK™, and she did everything it told her to do. “It was like throwing a giant net to catch a minnow,” she said. “Over time you think, ‘OK, that was unnecessary—not useless, but perhaps too much.’ We didn’t really need to be that robust, but we needed to start standardizing projects.”

As time went on, Frasqueri-Molina honed the management process. What worked for individuals? What worked for the team? What did they like? What didn’t they like? Once she and her colleagues figured that out, things started to work really well. Sometimes this meant slowing the process down a bit, which didn’t sit well with everyone in her department.

She learned the value of taking the time to explain the method behind the perceived madness. “This is what was happening in the past, and it didn’t work, this is why we’re doing it this way now,” Frasqueri-Molina would tell colleagues. “What do we have to lose?” She didn’t intend to squash enthusiasm, creativity, or energy; she just wanted to get the job done right.

Frasqueri-Molina and her department found a way to see not only how their individual work fit into the bigger picture, but how their technology group collectively fit into the rest of the animation company. Along the way, she evolved into a project management enthusiast. “I’ve come from this sort of primordial, chaotic ooze.”

Telling the PM Story

At a company powered by imagination, creativity, and a dash of pixie dust, infusing project management into its work might seem anathema to the Disney way. Not so. The company’s famous “blue sky” thinking lets its artists and engineers explore every curiosity, every possibility, and improbability, before project managers get involved. While this might be viewed as stifling, project management serves to streamline the creative process into a deliverable product. It brings order to a chaotic process.

“There have been people in history who have built amazing things, most likely using some sort of process,” explained Frasqueri-Molina, listing off marvels like the Parthenon, Colosseum, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and the Pyramids of Giza. “I don’t think they used Agile, but if they did they didn’t call it Agile,” she said. “These amazing feats of engineering were created by somebody who was running the show and had to deal with workers, risks, and bring in the money, perhaps from a rich patron.”

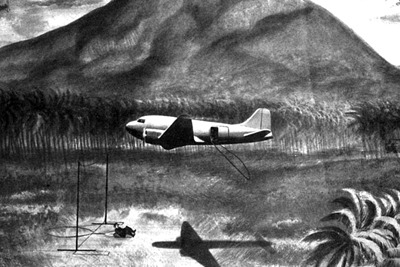

With Cinderella’s castle in the background, the seven STS-118 crew members march down Main Street at Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom theme park.

Photo credit: NASA/George Shelton

Frasqueri-Molina has created a first-of-their-kind workshop to tell this side of the story of project management to the Disney workforce. “Humans have been doing project management for thousands of years without a PMBOK™, Scrum, Agile, or RUP,” said Frasqueri-Molina. “The idea is to get people comfortable with the basic, universal concepts that they already naturally understand. Everyone understands that in some cases, something must be done before something else can happen. In project management, we call that ‘task precedence,’ which helps create network diagrams. Those are just the technical terms for what you already do every day.”

The idea for the workshop grew out of Frasqueri-Molina’s experience during Disney’s 2010 “Summer of Creativity and Innovation.” The event was designed to get employees to network, try something different, and spark conversation and innovation. In the midst of her own department’s transformation, Frasqueri-Molina had hoped to encounter something related to project management. She mentioned the absence of a project management outlet to Dan Davidson within the Learning and Development Department. The concept lingered until the following year.

When Molina presented at the 2011 NASA PM Challenge in Long Beach, California, the response she got from the attendees brought the workshop idea back to the surface. “There seemed to be interest around being able to learn more about the good basic practices of project management,” she said. She revisited the Learning and Development Department. The time was finally ripe for both parties to put the concept in motion.

Wernher von Braun (right) poses next to Walt Disney (left).

Photo credit: NASA

She proposed the workshop, which is scheduled to pilot this fall, as a modest first step in a larger process toward creating a gateway into the world of the project management that would encourage the workforce to advance their management education. “What you’re doing is starting to think about the skills you learn in the class and apply them to a larger scale,” said Frasqueri-Molina. The workshop is not meant to prepare someone to walk up to NASA and declare they will manage the next Pluto mission. “You would be able to understand the language of someone in project management and what they’re trying to accomplish. You’ll see if project management is right for you.”

“In essence, it comes down to understanding the fundamentals of project management and the structures,” she explained. “Do you want your structure to be in the shape of a triangle? Do you want it to be in the shape of a square? Then you figure out what that means, what processes make up the inside. The structure should be somewhat custom made. Only you and your colleagues will know what is best for your projects.”

For Frasqueri-Molina, fifty percent of being a good project manager is having the right attitude. “No structure, no fundamental understanding of the project management concepts, are going to help you if you don’t have the right attitude,” said Frasqueri-Molina. “Nobody’s going to want to work for you, regardless of how amazing you are when it comes to concepts and structures of project management, if you’re an unpleasant person. Your relationships to your stakeholders, how you interact with them, and how you understand them, that’s the linchpin.”

The Whippersnapper Cycle

Frasqueri-Molina was born into Generation X, but grew up with the Millennials. “I was all about cable television, microwave ovens, video games, and how technology was going to shape my future,” she explained, noting that her coming-of-age moment was the late 1980s. “Michael Jackson was still walking around with the glove and red jacket.ET and Return of the Jedi were on the big screen.” This notion of being on a generational “cusp” has made Frasqueri-Molina highly observant of generational differences in the workplace.

“Facebook might not draw somebody who was born in 1922. Whereas a place like Disney, that’s been around for 90 years, has a very long history and will probably have those traditionalists because it’s a long-time, stable, family company,” Frasqueri-Molina said. While Facebook might not appeal to a traditionalist today, it may in the future. After all, Disney was once a “young, whippersnapping, upstart company,” she pointed out.

Uniting generations through mutual understanding is central to organizational progress. “Millennials are just on fire,” said Frasqueri-Molina. “They have to save the world and do everything right now.” The energy and drive of Millennials is critical to progress, she stressed. “You cannot create the amazing things that really push our country and our generation to the next level without that whippersnapping generation. You need that next generation that will create that unexpected, unimaginable thing. That’s their job, to create that unexpected, unimaginable thing because nobody else can do it. Only they can.”

In her experience, inserting generational “cusp” people into a multigenerational group helps alleviate stark differences. Cusp people speak the language of two generations: the one they were born in and the one they grew up in. Frasqueri-Molina finds she has the ability to build a bridge between a Twitter-centric 26-year-old and a “phone-call-is-enough” 47-year-old. Everyone appreciates having his or her intelligence and genius recognized, explained Frasqueri-Molina. “That taps into something innate in everyone: the need to be a part of something, to be recognized. That, I think, is cross-generational. I’ve found that if I approach people that way— with a humble attitude that respects their contributions regardless of generation—it usually works out really well.”

Follow Taralyn Frasqueri-Molina on Twitter (@PML33T)

Read Taralyn Frasqueri-Molinas blog for the Project Management Institute.

Read The Disney-von Braun Collaboration and Its Influence on Space Exploration.