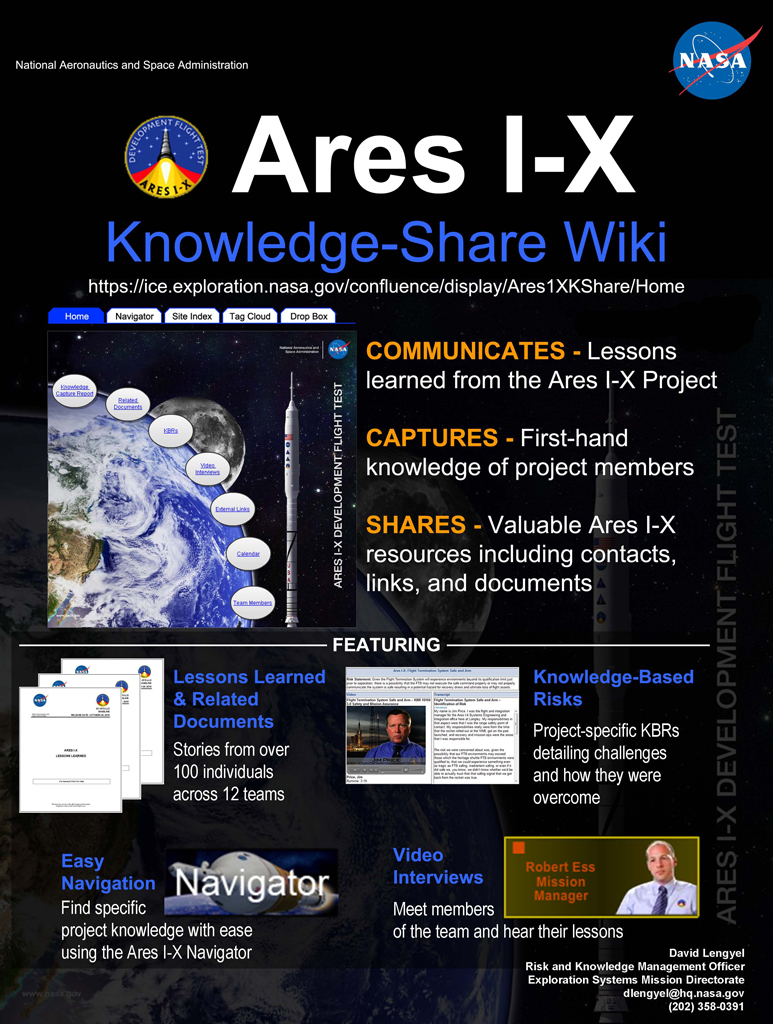

A close-up camera view shows Space Shuttle Columbia as it lifts off from Launch Pad 39A on mission STS-107. Photo Credit: NASA

June 14, 2011 Vol. 4, Issue 4

Space policy remains a moving target in the post-Cold War era, according to space policy representatives from six presidential administrations spanning 35 years.

A close-up camera view shows Space Shuttle Columbia as it lifts off from Launch Pad 39A on mission STS-107.

Photo Credit: NASA

Officials from the Carter to Obama administrations gathered for “Evolution of U.S. National Space Policy,” the latest George C. Marshall Institute event co-hosted by the Space Enterprise Council and Tech America on May 20, 2011.

Throughout the history of spaceflight, space policy has been driven by core themes, including U.S. leadership in space, environmental monitoring, private sector integration, national security, and technology development. Shaped by both economic conditions and international relations, these themes have built upon one another and evolved over the course of each presidential administration.

In its first 30 years, space policy was inseparable from the politics of the Cold War. When the standoff with the Soviet Union ended, space policy faced an identity crisis. “That sense of animation, that sense of motivation was removed. We had a series of concerns right away with the end of the Cold War,” said Mark Albrecht, former executive secretary of the National Space Council during the first Bush administration. “This is where it gets interesting.”

The question facing policymakers was what space policy should look like in the post-Cold War era. Precision guided munitions during Desert Storm in 1991 made the case for sustainable military space applications. At the same time, NASA was in a state of dramatic transition. It was still recovering from the Challenger accident. The space station had increased in cost by 400 percent. Early discussions about global climate change led to plans for large Earth-observing satellites, which were later deemed unsustainable and restructured into smaller missions. The “Faster, better, cheaper” methodology began to reshape the agency’s approach to spacecraft development.

The panelists addressed questions about how the issue of increased costs and decreased capabilities relates to space policy. Government institutions have become old and increasingly bureaucratic, some panelists said. A burdensome procurement process drives up cost, and any long-standing reliance on one type of space transportation (e.g., the shuttle) isn’t sustainable. Panelists agreed that the system needs to find ways to become quick and nimble again in order to address these issues.

Richard DalBello, former assistant director for Aeronautics and Space in the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) during the Clinton administration, reflected that this sentiment prevailed at the time. “I think the sense was that space was not as exciting as all of this. Space was slow, too bureaucratic, too expensive, and that there was some second and third guessing about the ultimate value of the investment,” he said, noting that the era was characterized by the rise of the Internet and rapid technology development.

An artist’s concept of the experimental X-33 plane during flight. The program was cancelled in 2001.

Image Credit: NASA/MSFC

DalBello also discussed technology outcomes during Clinton’s administration, such as the positive benefits of making GPS accessible to everyone and air traffic modernization. At the same time, DalBello and other panelists agreed that this was the beginning of a realization that there were unavoidable technology gaps holding exploration back. With the loss of the X-33 program in particular, DalBello said, “I learned a very important lesson: policy never trumps physics. You can say whatever you want, but if you can’t do it, it won’t happen. We just didn’t have the technology.”

This challenge of technology development persists to this day. There is a need for more “makers, doers, and dreamers,” said Jim Kohlenberger, who served at OSTP during the Obama and Clinton administrations.

Based on his previous experience in the second Bush White House, Peter Marquez, former director for space policy in the Obama administration, observed that, “We can trace failures in policy back to not the words that were written, but the failure to implement the policy.” Timing is everything. When it came time to roll out President Obama’s National Space Policy, he drew on lessons learned from the Bush administration and made sure to get it out quickly.

Bretton Alexander, former advisor on space issues at OSTP during the George W. Bush administration, said that the Columbia accident was a watershed event for the policy community’s understanding of human spaceflight capability. “With it came a recognition of the civil human spaceflight program as being fundamentally different than what we had thought,” he said, noting that the shuttle was not the operational system that many had assumed it to be.

Alexander also viewed the accident through the lens of long-term policy failure. “Within the organization there wasn’t a sense of why we were doing it, where we were going, the importance of it. That had been lost,” he said, citing the Columbia Accident Investigation Board Report’s assertion that there was a lack of a national mandate for the human spaceflight program. “It was a failure of national leadership over thirty years.”

The panel concluded with a discussion of the future of human spaceflight, where perspectives ranged from lamentation to optimism. “[There were] two incredible government accomplishments in 1969: we landed on the moon and we invented the Internet. But they took two fundamentally different paths,” said Kohlenberger, noting that the Internet moved into the commercial sector in the 1990s. “The difference is that we’ve kept space as an entirely governmental program.” He and other panelists discussed the promise of synergies between government and commercial space projects.

Read declassified space memos, directives, and policies prepared by the National Security Council starting with Eisenhower in Presidential Decisions.

Learn more about the Evolution of U.S. Space Policy event.