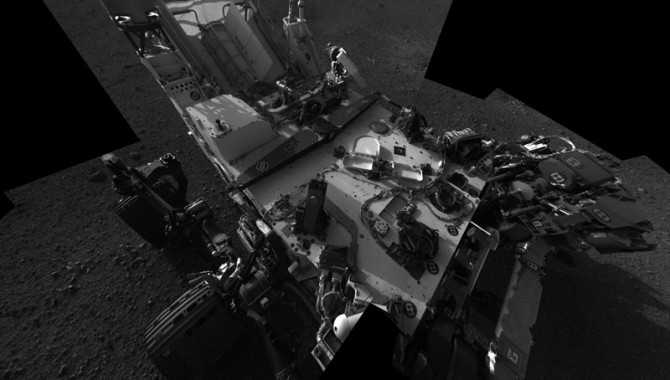

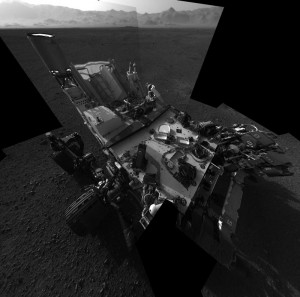

This full-resolution self-portrait shows the deck of NASA's Curiosity rover from the rover's Navigation camera. The back of the rover can be seen at the top left of the image, and two of the rover's right side wheels can be seen on the left. The undulating rim of Gale Crater forms the lighter color strip in the background. Bits of gravel, about 0.4 inches (1 centimeter) in size, are visible on the deck of the rover. Photo Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

August 30, 2012 Vol. 5, Issue 8

Knowledge is all around us at NASA. So why do we need a knowledge strategy?

This full-resolution self-portrait shows the deck of NASA’s Curiosity rover from the rover’s Navigation camera. The back of the rover can be seen at the top left of the image, and two of the rover’s right side wheels can be seen on the left. The undulating rim of Gale Crater forms the lighter color strip in the background. Bits of gravel, about 0.4 inches (1 centimeter) in size, are visible on the deck of the rover.

Photo Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The successful landing of the Curiosity rover represented a signal triumph for NASA’s Mars Exploration Program. The entry, descent, and landing (EDL) challenge for this car-sized vehicle required a different approach than had been used for previous Mars missions. As ASK Magazine Managing Editor Don Cohen noted in “The Sky Crane Solution” (Issue 47), the team drew on everything from Apollo data to the expertise of a Sikorsky helicopter pilot in order to design a system that would meet the mission’s requirements. Engineers looked back to the Viking program, reviewing documentation where available (much was not), talking to veterans of the program, reverse-engineering some existing hardware, and even retrieving a film of a Viking parachute test from a NASA retiree’s attic.

So what does this recent success have to do with the need for a knowledge strategy?

Curiosity is a great story with a happy ending. NASA’s Mars program has a deep bench of experienced engineers who represent a living body of knowledge about EDL. If you want to know how to land a vehicle the size of Curiosity on the surface of Mars successfully, these are the only people who have done it. As this team moves on to other projects, its knowledge will disperse, as surely as the knowledge that went into the Viking program did.

As NASA faces constrained budgets for the foreseeable future, the opportunities to put this knowledge into action are likely to be few and far between. There is a precedent for this gap. After the success of Viking in 1976, NASA didn’t launch another Mars lander mission until Pathfinder in 1997. Getting to Mars has always been expensive, and it will remain so for the foreseeable future.

Curiosity is far from the only mission to face this kind of knowledge challenge. The team that worked on the Robotic Lunar Explorer Program at Ames Research Center looked back to the Surveyor and Ranger programs of the 1960s and encountered the same kinds of gaps. “One of our Surveyor mission reports came from a consultant who happened to know a project manager from Surveyor, who gave him one of the few remaining hard copies of a document,” Butler Hine and Mark Turner told ASK Magazine in “A New Design Approach: Modular Spacecraft” (Issue 33).

That’s why a knowledge strategy is important. NASA practitioners need access to critical knowledge that can help them achieve mission success—now and in the future. That requires planning. The gaps in knowledge available from the Viking program didn’t threaten mission success for the highly seasoned Curiosity team. But it is possible to imagine a different outcome.

As NASA’s chief knowledge officer (CKO), I am heading up the establishment of an agency knowledge strategy in close collaboration with CKOs and knowledge leads at the centers and mission directorates. While the details of the strategy are still being developed, some of its core principles are already clear. It will integrate knowledge policy and requirements with those for program/project management; knowledge is inseparable from project success and should not be treated as a stand-alone discipline. It will focus on establishing both systems that make knowledge accessible and a culture that values learning and knowledge. Finally, it will respect existing knowledge practices and local customs while setting agency-wide norms for knowledge identification, capture, and dissemination.

Aware of the importance of capturing its own knowledge, the Curiosity team that performed the EDL sequence made sure to document its own work for future generations of Mars explorers. Their job is more or less done. The rest of us have work to do.