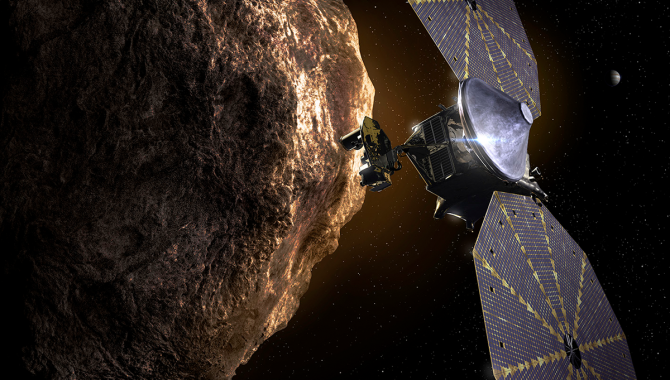

This artist’s illustration depicts the Lucy spacecraft passing one of the Jupiter Trojan Asteroids. Lucy will travel 4 billion miles in 12 years, passing by seven of these asteroids, believed to be remnants from the formation of the planets.

Credit: Southwest Research Institute

Lucy will travel ambitious trajectory to examine remnants from the early solar system.

On Feb. 22, 1906, German astronomer Max Wolf, pioneering a technique known as astrophotography, trained his wide-field double astrograph at the night sky and observed an asteroid that orbits the Sun in concert with Jupiter, about 60 degrees ahead of the massive gas giant. Wolf, who was the director of the influential observatory at the University of Heidelberg, named the asteroid Achilles, after the hero in Greek mythology.

In the 115 years since, about 9,800 such asteroids have been discovered. Known as Jupiter Trojans, statistical analysis indicates there could be far more of them—about 1 million greater than 1 km in diameter, clustered at Lagrange points either 60 degrees ahead of Jupiter or 60 degrees behind it, held there by the balance of gravitational forces from the planet and the Sun.

“…If you put an object there early in the solar system history, it’s been stable forever,” said Dr. Hal Levinson of the Southwest Research Institute, speaking at a NASA press conference. Levinson is the principal investigator of NASA’s Lucy Mission, which launched on October 16, bound for several flybys of the Jupiter Trojans. “So, these [asteroids] really are the fossils of what planets formed from. We understand the planets formed as these [objects] hit each other and grew and competed and these are the leftovers of that. So, if you want to understand where the solar system came from, you have to go to these small bodies.”

And the Lucy spacecraft will do that, twice. Lucy is named after the fossilized partial skeleton of an early human ancestor species found in an Ethiopian desert by Dr. Donald Johanson in 1974. Just as the Lucy fossils shed light on the origins of humans, the Lucy spacecraft will shed light on the origins of the planets.

The spacecraft will spend the first year orbiting the Sun before drawing its first gravity assist from Earth, establishing a two-year elliptical trajectory that culminates in a second Earth gravity assist in 2024. These gravity assists will increase the spacecraft’s velocity from 200 mph to 11,000 mph.

“After this, Lucy will have a close practice encounter with main belt asteroid Donaldjohansson, named after the discoverer of the Lucy hominin fossil,” said Coralie Adam, Lucy deputy navigation team chief, KinetX Aerospace. “In 2027, Lucy will finally cross into the Jupiter Trojan asteroid swarm.”

Between August 2027 and November 2028, Lucy will fly by five of the Jupiter Trojans—Eurybates and its satellite, Queta, Polymele, Leucus, and Orus—travelling about 15,000 mph and coming within 620 miles of them. Following another Earth gravity assist, Lucy will fly by equal mass binaries Patroclus and Menoetius in 2033, completing the primary mission, but remaining in a stable orbit that revisits the Jupiter Trojans, perhaps for thousands of years.

NASA’s Lucy spacecraft is moved from the Work Processing Cell to the Airlock inside the Astrotech Space Operations Facility in Titusville, Florida, on Sept. 29, 2021.

Credit: NASA

When NASA’s Associate Administrator for the Science Mission Directorate, Dr. Thomas Zurbuchen, first saw the proposed orbit of the Lucy mission, he thought, “…you’ve got to be kidding me. This is possible? Three Earth flybys, seeing the seven Trojans, and then an additional main belt asteroid on top. It just seems absolutely crazy,” Zurbuchen recalled at a NASA press conference.

The spacecraft that will accomplish this ambitious trajectory—traveling nearly 4 billion miles in 12 years—begins with a super lightweight composite bus that weighs just 300 pounds. It carries a suite of sophisticated instruments, including a long-range reconnaissance imager know as L’LORRI, a combined color imager and infrared spectrometer named L’RALPH, and a thermal emission spectrometer called L’TES.

L’LORRI uses a design similar to the Hubble Space Telescope to capture clear images of the asteroids and assist with optical navigation. L’RALPH will help determine the surface composition of the asteroids and search for the presence of ice. L’TES will help the team understand how fast a target heats up in sunlight and cools down in shadow, which will further contribute to understanding the surface composition.

“The engineering [had] to be designed to support the … science instruments we have on board, so that they can do their job,” said Joan Salute, associate director for flight programs, Planetary Science Division, NASA Headquarters, speaking at a NASA press conference. “Lucy will be NASA’s first mission to travel this far away from the Sun without nuclear power.”

To generate enough energy from the Sun, Lucy utilizes two massive circular solar arrays, each 23.9 ft. in diameter. The arrays deployed soon after launch, but one appeared to have not fully deployed as of October 19, and the team was examining next steps. The arrays were, however, generating nearly full power and enough to keep the spacecraft fully functioning.

“When we are near Earth, those wings have about 18,000 watts of power,” said Katie Oakman, Lucy structures and mechanisms lead, Lockheed Martin space, speaking at a NASA press conference before launch. Oakman noted that 18,000 watts would power several houses. “However, when we fly out to the Jupiter Trojan asteroids, we only have about 500 watts of power. So, that would only light a few light bulbs in my living room. And it wouldn’t be enough to power up my microwave… What’s really cool about our instruments is that they only need about 82 watts of power to collect science during our encounters.”

Lucy will travel five times further from the Sun than the Earth is, setting a record for a solar powered mission. Because the spacecraft will be exposed to temperature extremes from -250° to +300° Fahrenheit, the team tested it through two extreme temperature cycles at the Lockheed Martin facility in Littleton Colorado, simulating the heat near Earth and the extreme cold near Jupiter.

A United Launch Alliance V 401 rocket, with NASA’s Lucy spacecraft atop, powers off the pad at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station’s Space Launch Complex 41 in Florida at 5:34 a.m. EDT on Saturday, Oct. 16, 2021.

Credit: NASA/Kevin O’Connell and Bob Lau

“It took about 14 months to integrate the spacecraft bus and the instruments and verify the performance of the spacecraft and demonstrate that it would survive in the space environment over the full 12-year mission,” said Donya Douglas-Bradshaw, Lucy project manager at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, speaking at a pre-launch press briefing.

“I think the largest challenge in doing that, certainly, had to do with the pandemic. When you’re building hardware and integrating and testing it, there’s a lot of hands-on. We really had to reengineer the way we did integration and testing. The folks of Lucy are brilliant, and they very rapidly devised a way to be able to do that and do it confidently that we would maintain safety. And we were able to do that according to original schedule.”

The mission will provide window into the early solar system, perhaps 4 billion years ago, during the last gasp of planetary formation. The Jupiter Trojans appear diverse and scientists believe that diversity points to something fundamental about the history of the solar system.

“It’s important to see that as we look at nature, whether it’s looking at deep space, or whether it’s looking at the small objects, or even planets, that each one of them tells us a chapter of the story that we are part of,” Zurbuchen said. “If you pick up a rock, or you look at one of those planetary bodies, and you add science to it, it turns into a history book. And for me, that concept is just what I love about science.”

For more information on Lucy, listen to our podcast episode, “Lucy Mission”.