We celebrate NASA’s engineers who turn dreams into reality.

NASA engineers turn dreams into reality, solving complex challenges to push exploration forward. From landing rovers on Mars to advancing deep space missions, their ingenuity makes it all possible. This episode with Chief Engineer Joe Pellicciotti and Deputy Chief Engineer Katherine Van Hooser celebrates the innovation, dedication, and impact of NASA’s engineering community.

In this episode, you’ll learn about:

- Necessary skills for NASA engineers

- The value of stepping out of your comfort zone

- What’s ahead for NASA engineering

Credit: NASA

Joe Pellicciotti is NASA’s chief engineer. He began his tenure at NASA in October 2001, following a career in the private aerospace sector. Before his current position, Pellicciotti served as the deputy chief engineer, supporting the chief engineer in overseeing NASA’s engineering technical authority and programmatic policy. He also held the role of chief engineer for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, providing technical oversight for over a vast portfolio of space science missions in development. Earlier in his career, Pellicciotti was the Chief Engineer at the NASA Engineering and Safety Center (NESC) at the Goddard Space Flight Center and served as the NASA Technical Fellow for Mechanical Systems in the NESC.

Credit: NASA

Katherine Van Hooser is NASA’s deputy chief engineer, a position she holds at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. She began her career at NASA in 1991 as a turbomachinery engineer and has since held several key positions. From 2005 to 2013, Van Hooser served as the space shuttle main engine (SSME) assistant chief engineer and later as the SSME Chief Engineer, leading teams through the final 21 flights of the Space Shuttle Program. She was also the first chief engineer for the engines on the Space Launch System (SLS), NASA’s most powerful rocket. In her current role, Van Hooser is responsible for ensuring the technical success of all spacecraft, propulsion systems, science payloads, life support systems, and mission systems at MSFC, ranging from small instrument payloads to major components of the SLS rocket designed for deep space missions, including those to Mars.

Resources

NASA’s Office of the Chief Engineer

NASA Engineering and Safety Center

What Type of Engineering is Right for You?

Courses

Transcript

Andres Almeida (Host): Welcome back to Small Steps, Giant Leaps, the podcast from NASA’s Academy of Program/Project and Engineering Leadership, or APPEL. I’m your host, Andres Almeida. Each episode dives into the lessons learned and experiences of the people behind NASA’s innovative missions and research.

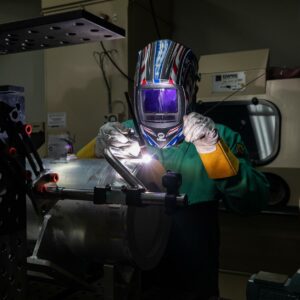

This March, we’re celebrating Engineering Month at NASA. It’s a time to celebrate the problem-solvers, innovators, and builders who turn bold ideas into reality. These are the people who tackle some of the toughest challenges in exploration.

Today we’re joined by NASA’s Chief Engineer Joe Pellicciotti and Deputy Chief Engineer Katherine Van Hooser. They’ll share insights into NASA’s engineering culture, the future of engineering, and how mentorship shapes the next generation of pioneers.

Joe and Katherine, thank you for joining us today.

Katherine Van Hooser: Thanks for having us.

Joe Pellicciotti: Yeah, this is great. Thank you.

Host: I’d love to start with asking: What message would you like to share with NASA’s engineers about their contributions to exploration and innovation?

Pellicciotti: So I want to let our NASA engineers know that I appreciate their incredible dedication to the mission and the safety of our crew and people. They’re relentless in their quest to collect and decipher data and provide benefit and value to the projects and programs that we have, whether it’s science, aeronautics, technology or human space flight, our NASA engineers are a national asset.

Host: Thank you. Katherine?

Van Hooser: Yeah, I think our NASA engineering workforce should understand that the contributions they make are critical to the success of our missions. Over my career, I’ve seen so many very specialized disciplines in which NASA is lucky enough to have the best folks in the world at what they do in so many areas.

We’re also fortunate because we are able to gain a lot of experience across so many, such a wide variety of missions across the whole NASA portfolio, and I’ve seen multiple examples of where our industry partners have come to us for help in a variety of areas. And that’s great because it means our engineers get to work on the very hardest problems that face our industry. What engineer doesn’t believe that’s the dream job, right, focus on the hardest problems there are in their field?

And, and so they should understand that the impacts they make on those programs are not only substantial, but they’re also necessary to the success of the NASA mission.

Host: So, engineering at NASA covers a vast range of disciplines, from aerospace to robotics, material science. Can you both share some examples of how NASA engineers collaborate across all these different areas of expertise? Katherine, can you start with that?

Van Hooser: Sure, I’ve seen many times. You know, when we approach a problem, typically, we like to make sure that all the associated disciplines are “in the room” in this day of virtual meetings and teams that exist over a lot of different centers and industry partners. We’re not always physically in the same room, but, but in the same meetings, in the same discussions and I think we try to promote a culture where people are not afraid to ask questions. And so often you’ll have somebody in one discipline question the work of another discipline, just for their own understanding or to see if it impacts them.

And sometimes it can spark a new line of questioning or a new innovative approach to a problem that may be a multi-disciplined approach, you know, where we hadn’t thought that was what was necessary before. So, I think that that happens a lot. Yeah,

Host: Yeah, Joe, do you have any insights there?

Pellicciotti: You know, in my tenure as NASA chief engineer, one of the areas I’ve been really trying to focus on is systems engineering, and I really feel like that starts kind of at a low subsystem level. We have a lot of new engineers that come in and then come in maybe as component engineers, but you start to see that even as a component engineer on a spacecraft system or aeronautics system, you need to interact and interface with many other disciplines.

So, these folks come in, and I might be, say, a mechanical systems engineer or something like that, but I need to interface with thermal engineering, with electronics, with avionics, maybe with propulsion. So, even at a very low level and at a very early stage of your career as a NASA engineer, you’re interacting with all these other disciplines. And as you build on your career, and you move forward and you get to bigger and bigger systems, from the subsystems to the major systems, it’s just more of that interfacing and more of that interaction. I don’t think there’s anything that we could do by ourselves and not rely on all those other disciplines to make up the whole entire project or be successful on the mission. I think that’s really important.

Host: And would you say, Joe, that oftentimes you should also familiarize yourself with the science itself? Does that happen often?

Pellicciotti: Oh, absolutely. In fact, it’s funny, because, you know, I’m an engineer by training and in my career. But I often get many questions about the science, and understanding the science of the missions is really important in understanding the bigger picture and how your system that you’re designing and building interacts to collect that science. I think that’s absolutely important.

Host: So, how does NASA foster mentorship and knowledge transfer within its engineering workforce.

Pellicciotti: You know, I really feel that it’s the responsibility of our senior engineers to make sure that we do mentorship of our earlier career folks. I brought up this example a few times, but unlike in the medical industry, where there’s university training for our doctors and physicians, and they tell them right up front, your job is not just to be a doctor or physician, it’s to be a mentor and a trainer for the earlier career folks. I think we need to do a better job with that in engineering and teach our folks from the very beginning that your job is not just to design and build great things, but it’s to teach the earlier career folks and mentor them throughout their career.

So, I really feel like it’s our responsibility as senior engineers to do that. And also we have a lot of assessments that we do in various areas, and I’m encouraging our senior folks to include earlier career folks in those assessments, so they learn from the people that have the experience and to grow in their career as well.

Van Hooser: Yeah, I completely agree. I’m a big fan, actually, of in-person work, having a collection of people in an office together. I’m also a storyteller, and I like the idea of, you know, somebody faces a problem, and the guy in the next cubicle, who’s been here for a long time, inevitably has a story about when he’s faced a similar problem, right? I think you learn from those stories better than if you were to look for a report or look in some database of lessons learned, that kind of thing. Those tools are useful but, but I think you need the story to prompt some of the memory retention aspect of that.

I’m also a huge fan of hands on work and I think one of the things that, you know, Joe and I continue to talk about and praise the benefits of are having small pieces of our programs and projects that our folks can do in house on their own, whether it’s, you know, testing some small subcomponent or coming up with a risk mitigation plan that involves a new material or a new design. And I think you learn a great deal by doing, you know, jumping in, getting your feet wet, and it’s even better if you can do that alongside some engineer who’s got some more experience.

So, those are the big things I think that can help teach our people how to teach our folks how to be better engineers and how to approach problems a little better, although

Host: All of that sounds like a rewarding part of the experience of being an engineer at NASA. But what else makes engineering a rewarding profession, Katherine?

Van Hooser: Well, I mean, an engineer gets to enable the dreams of a scientist, right? A scientist can think of these lofty goals, these, you know, unbelievable things they want to go learn about the universe. And it’s the engineer who says, “Yes, I can develop an instrument that can do that,” or, “Yes, I can build a rocket that can propel this instrument to the outer planets or out into the universe,” and we’re the ones who get to figure out how to safely put humans into space and bring them back home again. And what engineer doesn’t want to do things like that?

You know, that’s why I came to NASA. I came to NASA to be able to put people in space. And I’ve loved every day I’ve been here. Every day is a new problem, and you get to work with the best experts in the world and helping to solve these problems, and I can’t think of a better job.

Host: What do you say, Joe?

Pellicciotti: Yeah, I don’t know that I could say it much better than Katherine. But, you know, look at the products you know that we produce. [The] James Webb Space Telescope, probably the most complex telescope that we’ve ever built and put into space, reaching further back into the universe than than any other mission. SLS [Space Launch System], and what we’ve done, you know, the most powerful rocket ever built, brought to fruition, and it’s going to take, you know, our folks back to the Moon and to other, you know, other planets, potentially.

You know, Mars rovers putting – we’ve been putting rovers on Mars for, many, many years, and we’ve been able to take a look and at the pictures, at the science, and see if we find any kind of signs of life. I mean, it’s just been amazing. Voyager, that goes out to the edges of the solar system and beyond. And what engineer would not want to produce a product like that?

We can imagine, you know, we build it and then we enjoy the science and the product that comes back from it. You know, I really believe that the engineers are kind of the unsung heroes. They’re not always in the limelight, like the scientists and the astronauts and so forth, but the engineers are the ones that put all this together. And I think many of them, you know, enjoy and appreciate kind of being in the back room making all this happen. But I think there is a significant amount of reward that they get from the products that they build and the all the science that comes back and so forth. So, I think it’s great.

Host: What are the biggest changes you’ve seen in engineering, and what are some of the constants, what really doesn’t change?

Pellicciotti: I think some of the biggest changes, at least more recently, have been in the digital area and AI world. You know, we are really starting to make strides as that technology advances.

I mean, sometimes it feels like we’re trying to just keep up with it, but we are really doing quite a bit. I mean, there are, and I’ll talk about this maybe a little bit later, but the advances in digital engineering with respect to efficiency, design efficiency, reducing schedules, reducing mass, which is a huge metric for our missions. You know, the lower mass that we can build our vehicles with, the more payload we can put into orbit, and the lower cost. So, I just think that that’s one of the biggest changes.

As far as constants, you know, I try to stress to our folks, especially in systems engineering, that we can’t forget the training that we had and how we build a product and what we have to go through to get from a formulation of a design to, actually, implementation. And don’t forget those steps. In a digital world, it’s very easy to push a button and get a result, but you really need to understand how you got that result, so you can go back and take a look at it and say, “Hey, does this make sense or not?” But that whole engineering rigor that you have really hasn’t changed.

And, you know, the steps we go through, for example, in life cycle reviews, going through concept reviews, preliminary design reviews, critical design reviews – even in a digital age, you still need to go through those steps and look at your peers and look at the designs and make sure that that you’re doing the right thing.

Host: And how about for yourself, Katherine?

Van Hooser: I’m not sure I can say that any better than Joe just did. I think the constants are the way we approach a problem, the questions we ask, the rigor that we try to put into approaching and solving the issues that come before us. In my mind, what’s gotten better are the tools.

You know, early in my career – and I’ll date myself – early in my career, I remember, you know, some of our analytical solutions would take days to run on a supercomputer, and we’d have folks fighting for time on the computer at Ames just to get a solution out. And now those same level of solutions, and probably even better ones, are coming from, you know, somebody’s laptop that they’re, they’re running, you know, multiple times in a day. And so, the tools have gotten a lot better, which is great because it lets us explore more problems and find, you know, multiple solutions or options for programs. That’s where I think we’ve gotten a lot stronger.

Host: That brings me to the question of how you see the advancement of AI technology and digital engineering shaping the future of NASA engineering itself? Katherine, go ahead.

Van Hooser: Again. I’m going to date myself. The AI and digital engineering stuff, you know, a lot of times what we’re able to do in those arenas just makes me feel really old [laughter]. Such amazing things can come out of those technologies. And we’ve got to figure out how to use AI and figure out how to make more of our digital tools work together more efficiently, or else we’re going to get left behind.

And I think, I think a lot of the amazing things we’re doing today, we’re able to do because we are seeing a, like Joe said, a systems engineering point of view on the problem, right? How do we make the designer be able to more easily take his design and send it to the analysts all electronically? You know, no more paper drawings, no more “the analyst having to convert one model to another” thing. It should all happen seamlessly, and that can enable us again, to be a lot more efficient and help our industry partners be more successful and have more options as we move forward.

AI, I think we’re just getting started there, and I can’t wait to see what kind of benefits we can get from that technology, and can’t wait to see what the engineers do with it, right? They’re always coming up with innovative ways to use tools, and I can’t wait to see the products that come out.

Host: How about for yourself, Joe?

Pellicciotti: Yeah, so I think the one key thing is that we can’t forget about the fundamentals and the fundamental physics that goes into our engineering. I think we’re seeing huge advancements in digital engineering and AI, and I think we need to learn to be able to work with it to the benefit of our projects.

And we’ve been doing some of that, you know, for example, I’ve seen, I’ve seen cases where we’ve taken the design of a product and we’ve used AI to make that design more mass efficient, more stiffness efficient, and so forth. In the end, you know, we can take that design, and we can test it and make sure it still meets all of our qualifications, but that design has… it’s taken less time to go through the process. It’s more efficient, which lowers cost. So, that’s a way of learning how to work with the systems that we have but not forget about the fundamental physics and what we need to qualify our systems, you know, to make sure that they’re successful on orbit and a successful mission.

There’s areas where we’ve used virtual aids to help with integration. So, again, part of the digital engineering, we can now reduce integration time, because now we can take virtual models and look at where we need to be, how we’re going to integrate electronics and hardware and prop systems and so forth before we ever get to that point. So, it reduces the amount of time of trial by error – “Well, I can’t reach in here. I can’t fit in here” – to get to this point in the system.

So, really, we’ve seen advances already, and that’s just going to continue to grow. And as it gets bigger and bigger, and we qualify and validate more of these systems will, it’ll just accelerate exponentially. So, I think there’s huge advancements, and it’ll grow outside of engineering itself into other parts of our design phases that we go through, as far as project management and so forth. So, it’s really good, and I think there’s a there’s a very positive future in it.

Host: It sounds like it, and NASA success is built on a legacy of innovation and risk-taking. So how do you encourage a culture where engineers feel empowered to take bold these creative new approaches to problem solving, Joe, if you can continue there?

Pellicciotti: Yeah. So, for me, one of the ways is to recognize and showcase folks that that are being innovative. We have a systems engineering conference that’s mostly internal. There’s several hundred engineers that that go to that on an annual basis. And we have awards, technical excellence awards for, that are offered for every one of those sessions, and one part of that is innovation in systems engineering. So again, to recognize folks that are doing that is really important.

I think we also need the resources, because usually when folks want to be innovative, it’s a low technology readiness level for a lot of that, and that takes a certain amount of resources to, to take those to the next level. So, fighting for some of those resources and making sure that the agency has a vision that includes that is really important to help foster this innovation of some of the you know, the engineering cadre.

And the other one is to encourage collaboration across centers and tap into senior expertise. I really believe that folks need a basic understanding of how to build spacecraft systems or aeronautics systems before they can be innovative. You can be innovative, but you need to know some of the basics of how we operate in space, for example. So, tapping in, you know, matching the earlier career folks, or the innovative folks even if they’re seeing more senior folks, with the people that have the expertise, is really important because that will help to take that innovation to the next phase, which would be implementation into our missions.

Host: Katherine, what are your thoughts there?

Van Hooser: Yeah. So, I talk with a lot of groups about risk leadership, and I think there are a couple of aspects there that I continually try to help our workforce understand. One, you know, not every program and project has to have the same level of risk acceptance or risk tolerance, right? What’s right for a small instrument science payload, you’re able to take a little more risk than you might take on a human spaceflight mission. And so, we cannot approach every problem with the same, same level of expectation at success and, and technical rigor, right?

So, we also need to help folks understand that if we’re going to take more risks, with that comes an, a chance at increased levels of failure as well. And sometimes that’s okay, right? Some of our smaller programs and projects, it’s okay to take a little extra risk. We need to help the engineers understand that, you know, it’s our job as engineers to help a program understand and identify the risks they have to clearly articulate those risks to the program, and then help identify mitigation solutions and bring options, right?

We can do a certain level of testing and analysis, and it’s going to take, you know, six months and, but deliver an answer that is 90% accurate. Or, I can do a three-week version, and it’s going to be less accurate, but maybe that’s all you need, right? Let’s present our decision makers with some options and let the decision maker make the decision and remember that the program manager is the one who owns the risk.

So, it’s up to us as engineers to bring innovative solutions and talk about the implications of applying those innovations, and then, you know, support the decisions that that are made by the project managers and the leaders and, in certain cases, that are equivalent with the risk level or tolerance level of that program or project.

Host: I have one final question for you both, and that is, what was your giant leap, Joe? I’d love to start with you.

Pellicciotti: I’m going to start with my, I’ll call it a big leap. And so, I spent about 15 years in industry, and then, you know, I became a NASA civil servant, you know, potentially giving up some opportunities for the NASA mission, and that was really important, and I’ll never, ever regret that. I think I’ve had an awesome career at NASA and in industry as well. So I would never give that up.

But I think my giant leap was a little bit more than that. It was, really, moving -. When I joined NASA, I came into a center, and they’d had, you know, there’s a certain amount of isolation that you get working specifically at a center, and then I moved to get to a position where I had a more agency perspective. So, you kind of drop that parochial perspective that you have to look at the overall agency. And what I found was that, you know, there were not only great engineers at the center that I joined, but there are great engineers all over the agency. I was fortunate to be in a position where I got to interact with engineers at the agency, but also with space engineers in industry and academia, and it was incredibly rewarding in my career.

And I think for me, that giant leap was going from that parochial perspective within a certain company or within a certain center to kind of an agency, or more global perspective of what is out there, and all the smart and talented people that I – that I had the opportunity to work with.

And the mission that we have at NASA is just incredibly exciting, and I’m looking forward to the opportunities ahead that we have, both with industry and within our own agency.

Host: All that exposure really helped round you out, it sounds like.

Pellicciotti: Absolutely.

Host: And how about you, Katherine? What was your giant leap?

Van Hooser: I spent the first part of my career working in turbo machinery and liquid rocket engines. And I loved that, right? I truly loved that hardware. I loved being able to take a physical thing and help get it to flight.

I became the chief engineer for space shuttle main engine, and either in that position or as deputy, I got to be there for the last 21 shuttle flights, and I think I got pretty good at my job. It was definitely my comfort zone to work on liquid engines, but at one point, the director of engineering at my center asked if I would take a position as deputy director of our materials and processes lab. He saw I had some leadership skills that could help with some leadership issues they were having in the in the lab at the time. And I knew he was right, and I’d had a former boss who told me, you know, you reach a point in a career, in your career, where you’re ready to give up the thing that you are most passionate about and love, and you recognize that you can use your skills to help a broader group of people, or, you know, help out the organization at a broader level, or help the agency a little more. And I recognized I was at that point in my career, so I moved to the materials and processes lab, and I loved it there.

And I wouldn’t be where I am today if I had not taken that giant leap out of my comfort zone, right? And now I get to see our entire portfolio of projects. I get to meet these amazing engineers all across NASA who do unbelievable things, and it’s all because I took that first giant leap out of my comfort zone.

So, that’s one message I think that comes along is: Don’t be afraid to use your skills at a, at a higher level, even if it means giving up a thing you love and doing something a little hard and scary. But I think it also says, you know, you have to recognize that that next opportunity that comes along may not be the dream job you thought that was your next step, but you have to be open minded about it, because it may lead to even better things than you could have expected. So, you know, recognize each opportunity for what it has to offer and for the doors that it can open beyond, beyond that next step.

Host: I love that theme you both shared about stepping out of your comfort zone. That’s a critical part of growth.

Van Hooser: I think it is I, you know, I had been working in engines for a while, and I’d had several people approach me, “Why don’t you apply for this job? Apply for this job.” And I asked my boss at the time, I’m like, “How many times can I say no? Is it okay if I don’t go apply for these things? I love what I’m doing.” And that was when he told me, you know that, “Yes, you can say no, you can keep doing the work that you’re doing. It’s valuable and you’re good at it, but there will come a time when you’ll see you’ve got something to offer to a broader arena.” And eventually that time does come. And he was right, there’s a lot of value in trying to work at a different level. You get to see more things, influence more things and enable other people to have those comfort zone jobs and the jobs that they love and be really good at them. It’s, it’s very impactful.

Pellicciotti: You know, I think there’s a, an interesting perspective that I’ve had at least, which is that, you know, every time that I’m maybe a little bit nervous going to that next, taking that next leap into that next type of job, I find myself reflecting back after I’ve taken it and thinking, “Wow, that was probably the greatest job I ever had.” And that just keeps happening. “You know, even though I’m in a challenge right now, I’m looking back at the thing I did just before that, saying, “Boy, that was one of the greatest jobs I’ve ever had”.” And then you take that next step and say the same thing again. It’s just really rewarding.

Host: Well, thank you both for your time. Really appreciate hearing from you, and I hope the NASA engineer workforce does as well. It’s very insightful.

Pellicciotti: Thank you. Thank you so much.

Van Hooser: Thanks for the opportunity.

Host: That’s it for this episode of Small Steps, Giant Leaps. For more on Joe and Katherine, and Engineering Month, visit our resource page at appel.nasa.gov. And don’t forget to check out our other podcasts like Houston, We Have a Podcast, Curious Universe, and Universo Curioso de la NASA. Thanks for listening.

Outro: Three. Two. One. This is an official NASA podcast.