NASA Astrophysicist and Pioneers Program Lead Scientist Michael Garcia discusses the new program’s first mission concepts selected for further development.

NASA selected four small-scale astrophysics missions in January 2021 for further development. The mission concepts use small satellites and scientific balloons, and enable new platforms for exploring cosmic phenomena such as galaxy evolution, exoplanets, high-energy neutrinos, and neutron star mergers.

In this episode of Small Steps, Giant Leaps, you’ll learn about:

- Science Mission Directorate plans to do high-impact astrophysics experiments on a small budget

- Aspera, Pandora and StarBurst SmallSat missions and the PUEO balloon mission

- The process for proposing a future concept study in the Pioneers Program

Related Resources

NASA Selects 4 Concepts for Small Missions to Study Universe’s Secrets

APPEL Courses:

Science Mission & Systems: Design & Operations (APPEL-vSMSDO)

Michael Garcia

Credit: NASA

Michael Garcia is an Astrophysicist at NASA Headquarters and the Pioneers Program Lead Scientist. Garcia also serves as the Astrophysics Research and Analysis Program Lead, Hubble Program Scientist, ATHENA Program Scientist and Astrophysics CubeSat Lead. He began his career in astrophysics as one of the multiple amateur astronomers who built their own telescopes in high school. He used it to study Apollo landing sites. Garcia worked on the AXAF (renamed Chandra) High Resolution Camera team and ROSAT High Resolution Imager calibration before taking the lead in finalizing the Einstein Observatory data archive. After the Chandra launch, his research turned back to multi-wavelength studies of black holes and neutron stars in our Galaxy and extended to time-domain studies of black holes in our nearest neighbor, the Andromeda galaxy. Garcia has authored or co-authored over 300 scientific papers. He has a bachelor’s in earth and planetary sciences from Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a master’s and doctorate in astronomy from Harvard University.

Transcript

Michael Garcia: It is just spectacular cutting edge — some people would even say, possibly, Nobel Prize-winning science.

And they cover a huge range of astrophysics from the highest energy particle astrophysics, the gamma-ray astronomy to ultraviolet astronomy, and then an exploding field — exoplanets.

I love the fact that we’re able to use these small satellites to do this kind of thing. This would not have been possible a decade ago.

Deana Nunley (Host): Welcome to Small Steps, Giant Leaps, a NASA APPEL Knowledge Services podcast where we tap into project experiences to share best practices, lessons learned and novel ideas.

I’m Deana Nunley.

A new NASA program that sets the stage for doing high-impact astrophysics experiments on a small budget selected four small-scale missions in January for further concept development. Michael Garcia is an astrophysicist at NASA Headquarters and the lead program scientist for the Pioneers Program.

Michael, thank you for joining us.

Garcia: You’re welcome. My pleasure to be here.

Host: What is the Pioneers Program?

Garcia: So, Pioneers is a new program. It’s an annual solicitation and it’s for SmallSats, CubeSat swarms, stratospheric balloons, and space station, attached payloads. It is a light touch research and analysis program. The PI costs are capped at $20 million. That’s for them to design their mission. NASA pays for the launch. That means we guarantee we’ll get you into space or on the end of a balloon that is almost in space. And it’s a program that’s aimed really at young and university teams.

Host: Why is the time right for something like Pioneers?

Garcia: Good question. The time is right because there’s just been an explosion in small satellite technology. Think of the SpaceX Starlink Fleet, OneWeb, Planet Labs. These commercial companies are flying thousands — I mean, in the case of Starlink, 40,000 identical, small satellites. So that makes the buses, the spacecraft, really available much, much cheaper than they ever had been. And this is something that NASA has been supporting for a long time, or we’ve been supporting commercial space and it has paid off in spades. So now we’re able to buy a satellite that is one-tenth the cost of what it was 10 years ago, and price is going to continue to go down and the capability to continue to go up.

Host: What makes Pioneers different from other NASA astrophysics programs?

Garcia: It’s different in a lot of ways. So, for all of my NASA friends out there, it’s a 7120.8, not an NPR 7120.5 program. And for people who don’t know about those particular acronyms, it’s a research and analysis program. It’s along the lines of our Sounding Rocket Program, our Stratospheric Balloon Program. So those are programs in which we don’t do the kind of mission assurance, the kind of quality control that we do for true spaceflight programs. And in turn for that, we take a little bit higher risk, but we reduce our costs and we can do things faster. And it’s a program where we’re willing to take that little bit more risk to allow things to be done faster and cheaper. So, that’s one way it’s different.

Another way it’s different is that it really is focused on young principal investigators. And it’s part of the review process that we want to train the next generation of PIs here so they can go on and become the PIs for flagship missions or for large explorer missions. This is where they cut their teeth. And so for this first round, we selected four programs. All four PIs are brand new. They’ve never done a mission like this before. Three of them are very early career. One is more mid-career and half of them are women. And so, the women here have over performed because they were only about a seventh of the input pool, but two of the four are young female PIs. So it’s a program that we really see as a place to foster leadership and mentorship. Even though these PIs are new, they all have really interesting and well-thought-out mentoring plans to have people who have done this before advise them.

Host: We’d like to hear more about the PIs and these missions NASA selected in January for further concept development. Could you give us a quick overview of the concepts?

Garcia: Sure. So we selected four. We had 24 proposals. And what was really fabulous, that out of that 24, 22 of them were what we term selectable. So, we get to choose the absolute best of the best here, just the cream of the crop. There are lots of other great ideas that we hope will come back later. And these four, so three of them are indeed SmallSats. One of them is a stratospheric balloon, and they cover a huge range of astrophysics from the highest energy particle astrophysics, the gamma-ray astronomy to ultraviolet astronomy, and then an exploding field — exoplanets. The study of exoplanets. So they’re all very different, but they’re all the same that they’ve found a niche where they really can excel.

Host: Let’s delve into more specifics about each of the concepts, starting with Aspera.

Garcia: So yeah, the PI there is Carlos Vargas. He’s from University of Arizona, a young researcher, and actually his mentor is also pretty young. She’s a new professor at University of Arizona who came up through our Sounding Rocket Program. So Aspera is ultraviolet focused. It’s four small telescopes that are going to look at the outflow and inflow of hot oxygen from nearby galaxies. And what’s one of the really cool things about Aspera is that the technology for the ultraviolet area has really improved over the last several decades. I like to point out that the throughput of the Hubble Space Telescope, our premier UV instrument in space is only a few percent in the ultraviolet. So, to go from a few percent to even 50 percent is a factor of 10 leap. And Aspera does that. While it’s a lot smaller than Hubble, because the technologies have gotten so much better, its throughput in the ultraviolet is fabulous. So it can do some of the kinds of work that Hubble can do but in this very, very small package.

Host: And another SmallSat concept is Pandora.

Garcia: Right, Pandora, another really neat new program. The PI here is Elisa Quintana, Goddard Space Flight Center. A young early career, one of the few young female Hispanic astronomers around. It’s going to look at exoplanets. And it does something that I find fabulous is that we’re using technology that other people have developed. So, in this case, Pandora has about a half-meter telescope and DOD developed the telescope, so we didn’t have to pay for that development. I’m guessing that they use it to look down, but we’re using it to look up. So, it’s going to look at transiting exoplanets. So these are exoplanets to go across the star. And as they do go across, the light goes through the atmosphere of the planet. And that changes the spectrum you see from the star, but it only changes it a very small amount. And it turns out the stellar spectrum itself changes more due to star spots coming and going across the surface of the star.

That is a bigger effect than the change imposed by the starlight going through the atmosphere of the planet. So Pandora’s going to look at the star spot cycle and the atmosphere of the planet at the same time and in effect calibrate out this effect. So again, really, really cool idea, great to see a half-meter-sized telescope in this $20 million package. We have built in the past telescopes, half that size, that cost 10 times as much in other programs. They’re just in the study phase, right? So, we wish them the best of luck and hope that they’re going to succeed. But it really looks like it’s very cost effective.

Host: That’s going to be interesting to watch. And then there’s a third SmallSat – the StarBurst mission, right?

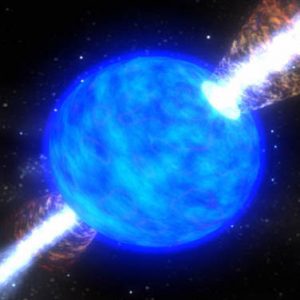

Garcia: Right, StarBurst. Now, we’re getting up into the higher energies. This is a gamma-ray mission. So similar to Aspera, it uses new technologies. There are existing gamma-ray burst monitors flying right now. The Swift satellite is one example of that, but it’s not the only one. And StarBurst is more sensitive because the technologies have improved. So, it will detect numerous gamma-ray bursts. And it’s really aimed going after short gamma-ray bursts. Short gamma-ray bursts are when two neutron stars collide rather than a neutron star turning into a black hole, for example. That’s another way you can get a gamma-ray burst. But when two neutron stars collide, this is actually the way you make most of the gold in the universe, so they’re really precious metals. And when the two neutron stars collide, you also see them with gravity wave observatories, with LIGO. So you see that ripple in spacetime.

So, the LIGO detectors, just coming online, this was the Nobel Prize. I think last year was the discovery of gravity waves, actual detecting them. It’s going to detect the gamma-ray burst at the same time as you get the gravity wave burst. And it will be able to do about 10 of these simultaneous detections a year. And that’s a factor of 10 more than anything else can do that’s flying now. So, again, we’ve got something in a small package, but because of the increase in technology it’s able to really leapfrog over our current capabilities.

Host: Really fascinating hearing all about these SmallSats. And you mentioned a balloon mission as well.

Garcia: Right. So there is one balloon mission. And of course, the program is aimed both at SmallSats and space station, attached payloads. We didn’t get any of those this year. And there were several ideas that people decided they’d hold off and probably propose later, but also long-duration balloon missions. And so, we do ballooning now, but the balloon length of the programs is maybe a month at the most. And they tend to be cost-capped at about $10 million. So here we’re at $20 million, so a factor of two more in cost and in capability. So this balloon mission is called PUEO. And the PI is Abigail Vieregg at University of Chicago. She’s a young researcher. Just a couple of years ago she actually won a fellowship, the Nancy Grace Roman Technology Fellow. So this is a program for early career technology people named after Nancy Grace Roman who many people say is the mother of the Hubble Space Telescope, actually.

So PUEO is going to look for the very highest energy neutrinos, and neutrinos are extremely hard to detect. They are known for not interacting with anything. So the way that PUEO works is it uses the entire Antarctica ice shelf as its detector. So, with that much ice, you actually can get interactions on the ice from these very, very high energy neutrinos and PUEO will try to detect them. And in a flight of a couple of months, it may only detect a few of these events. But if it does, it is just spectacular cutting edge — some people would even say, possibly, Nobel Prize-winning science. So it’s a little bit higher risk than the other programs, but that’s fine. That’s what Pioneers is all about. And when you have four different programs going on, it’s totally appropriate to have one that’s a little bit higher risk than the others.

Host: What’s the timeline on the concept studies?

Garcia: So, these four missions were selected in early January and they were selected on the basis of a peer review where a group of both engineers and scientists reviewed them for the scientific content and for the likelihood of success of their technologies. That review did identify some weaknesses in all four. And so their first job is to address those weaknesses, tell us how they can mitigate those risks. They have about six months to do that. When they provide us with that concept study report is what we’re calling it, we will review that. And any of them that make the case that they can get this mission done, do the science they propose to do and stay within the $20 million cost cap, we will take forward to launch.

Host: That’s going to be exciting.

Garcia: It’s going to be very exciting. Those studies are due in six months. We’ll spend a few months reviewing them. And then the timeline to launch is within five years. Some of them are going to be a little bit faster than that, some of the SmallSat buses are off the shelf, but fingers crossed, they may all make it. And that’s fine if they don’t. Again, we envisioned this program as something where we’re willing to take a little more risk than in other programs. So, that means that some of them won’t. I mean, I used to play a lot of hockey and I liken it to, ‘If you don’t fall down once in a while when you’re skating, you’re probably not trying hard enough.’

Host: Good analogy. Michael, what gets you most enthused about the possibilities with these missions?

Garcia: Well, I love the fact that they’re all first-time PIs. I think that’s fabulous. They have thought up some really spectacular science cases. They’re all doing really, really interesting things so I find that fascinating. And I love the fact that we’re able to use these small satellites to do this kind of thing. This would not have been possible a decade ago. The spaceflight technology and the availability of cheap rides up to space, that’s something that NASA has put a lot of effort into getting commercial space going, and it’s really paying off. It’s fabulous to see. There are several Space-X launches coming up where the crew is entirely civilian and that’s fabulous. Space tourism has started. So this great science is starting too.

Host: Do you have suggestions for people who might be interested in proposing future concept studies in the Pioneers Program?

Garcia: Sure. Dream big even though it’s in a small satellite. It’s very clear you can do great science in these smaller packages. Don’t get discouraged if you don’t get selected the first time. The competition is incredibly fierce. And these ideas are great. Take the weaknesses that the review panel finds and improve on them, hopefully. And then we try to make them useful to everybody so they can come back and write a proposal that’s even better the second time. So yeah, keep them coming. I mean, I love the fact that we had 24 proposals, that we had 22 really good ideas. I’d like to see more.

Host: And if you’re interested in learning more about the Pioneers proposal process and the topics we’ve discussed during the conversation, please visit our website – APPEL.NASA.gov/podcast. Michael’s bio and a transcript of today’s episode are also available along with the links to related resources.

Many thanks to Michael Garcia for joining us on the podcast.

A quick reminder…if you haven’t already, we invite you to subscribe to the podcast, and share it with your friends and colleagues.

As always, thanks for listening to Small Steps, Giant Leaps.