By Marty Davis

Start Dreaming

Let me tell you about a dream I have. This is one of those dreams with a capital D. It’s not the kind of dream in which you wake up feeling refreshed and well rested; rather, this is the kind of dream that keeps you up at night, wondering how to get it out of your head and into other people’s.

A little background first. As we all know, here at NASA requirements keep coming. Not surprisingly, they seldom go away. Reviews, for instance. Over the years we have seen many additional reviews laid on us. There are at least a dozen reviews in the life of a project. While I don’t mind doing a review — if I feel like I’m getting value out of it — when these things are thrown on helter skelter and there’s never a look at combining or refining them, then each new review feels like just another requirement, another hoop to jump through, which is frustrating because you’ve got to spend time and effort preparing for it.

So this got me to thinking — there must be a better way to do reviews. What I wanted was something quite simple, to combine as many of the reviews as possible. The External/Independent Readiness Review…The Independent Annual Review…The Pre-Ship Review…The Red Team Review… There is so much redundancy in all these — not to mention the many other reviews I won’t bother to enumerate — there’s got to be a way to streamline the process.

I wanted a review team made up of some internal people and some external people, and to bring this team in as part of the total review process. Use these same people throughout the entire lifecycle of reviews, from the very first design reviews to the last ones just before launch. If you brought this team in as part of the total review process, things could get checked off when they needed to be reviewed and you wouldn’t have to revisit them unless it was absolutely critical. You would also have the advantage of the same external people reviewing you earlier in the program.

Apprehensive at first, I shared this dream with a Goddard colleague. Guess what — he had the same dream. Maybe then there are others, we said to each other.

We both understood that if we were going to do anything significantly different in our own projects, there had to be changes across the board; so we met with our boss to try and get buy-in from him.

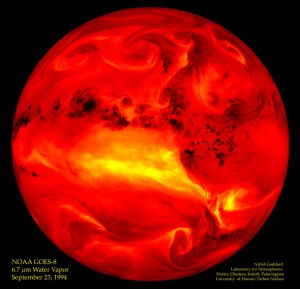

This image of Earth, taken by GOES-8 on Sept. 23, 1994, shows atmospheric water vapor observed at a wavelength of 6.7 microns.

What we were proposing was really just straight out of 7120.5a, the established framework for managing programs and projects within NASA. Within this we are allowed to do a certain amount of tailoring. Most people are reluctant to because it’s not so easy to get approval. Quite honestly, I was prepared to push for it on my project whether I could sell it to the Center or not.

The Other D-Word

There is a saying, “the devil is in the details,” and as it turns out that’s where the fighting often occurs too. Many of my colleagues agreed the status quo needed to be changed, but when I began spelling out how I wanted to do it, I could see I was going to have to fight for my way.

Some of our management at Goddard thought I was too involved in specifying what the composition of the review team should be. Indeed, I did specify the composition, but getting good people was the whole point as far as I was concerned. I was assigned an internal co-chair and recommended an external co-chair, and I told the internal co-chair that he could have 7 members including himself, and I said the same to the external co-chair. I also said to them, “Neither of you can duplicate the same technical specialties.” If one of them had a thermal person, the other could not. If all this sounds imperious, well, I’ve been at NASA going on close to four decades and when you’ve been here that long, you learn that to get what you want sometimes you have to get into the details.

Another thing that raised their hackles was that I wanted to bring outsiders into the review process right from the start. To my mind, internal reviews have only limited value. With internal reviews, you do a presentation, you answer questions, they give you requests for actions, and then they go away and you sit down and try to answer them. You mail them to somebody and they tell you whether they are unacceptable. What I wanted was something more like how External Reviews are conducted, where you give a half to a full day of presentation and then the review team identifies where they want to meet one-on-one. You’re being reviewed to a greater depth in selective areas. Something in the presentation that piques their interest is identified as something to review in more detail.

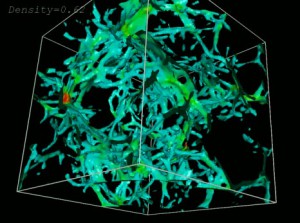

This false-color computer model of the early Universe is 30 million light years on each side. The green-shaded cobwebs are tenuous clouds of intergalactic gas.

While all this was being vetted by management, I did something else that gave people pause. I decided to go ahead and incorporate this approach into my reviews right away. I saw no point in waiting, as we still had several more reviews ahead and there are benefits, I believe, beginning at any point in the project. I put together the review team and we tried it out. My feeling was, let someone stand up and stop me. We held the first review using this model in February. The charter for this integrated independent review team (IIRT) was to find anything that could go wrong. The review lasted for two days, one day of presentation, one day of one-on-one, and then a caucus with the review team.

I think it worked. How do I know? One way is I ask myself, “Do I feel like they actually penetrated some areas with a reasonable degree of detail, and do I feel like I’ve truly been reviewed?” In this case, the answer is yes and yes. They identified areas of potential concerns and had thorough one-on-one discussions with our engineers. We had the opportunity to sit down and discuss the items and close them, and the ones we couldn’t close at the review we got a Request For Action (RFA).

To me this is the way a review should go. We left with just 5 RFAs because we worked the rest of them off in real time with the technical experts on our side and the technical specialists on the review team side. One-on-one discussions allowed us to convince the reviewers that we knew what we were talking about. That’s what the reviewers want, to have confidence that you approached this problem carefully and you have a process for solving it.

On the Horizon

I plan to use my tailored approach throughout the life of GOES N-Q. My boss has been very encouraging and a strong advocate for this at HQ. The Systems Management Office (SMO) here has taken the concept and tried to get buy-in from other centers. SMO has also gone to the Chief Engineer’s Office at HQ and gotten them to agree in the next rewrite of 7120.5 that a process like this should be recognized.

Many people regard reviews as something onerous, but if we can tailor them so that they’re not as bad as they have to be, it can be a great benefit to a project manager. A crack review team can help you identify problems in your project, and that may make the difference between mission failure and mission success. Plus, isn’t it comforting to have a review team, this team of experts, come in and try to penetrate areas in your project and tell you that you are doing things right?

Lesson

- Ensure that project reviews are for the one being reviewed and not for the reviewer.

- Reviews should encourage joint problem solving rather than just reporting. To do this, ensure that the review process is viewed as feedback from independent and supportive experts.

Question

Let’s indulge our dreams for a little while. How would you change the review process on your own projects if you were suddenly given the opportunity to do so any way you wish?

Search by lesson to find more on:

- Reviews