Retired Navy Captain and commander of Apollo 17 Eugene Cernan, center, is flanked by Apollo 11 Commander Neil Armstrong, left, and A. Thomaas Young, as he testifies during a hearing before the House Science and Technology Committee, Tuesday, May 26, 2010, at the Rayburn House office building on Capitol Hill in Washington. The hearing was to review proposed human spaceflight plan by NASA. Photo Credit: NASA/Paul E. Alers

April 26, 2010 Vol. 3, Issue 4

A group of NASA systems engineers peeked behind the curtain of the legislative process, learning what it takes to manage projects in a political environment.

Capitol Hill sits three blocks east and three blocks north of NASA Headquarters. While the distance between these buildings is short, the differences are vast. For four days, the Government Affairs Institute (GAI) at Georgetown University designed and conducted a program for civil servants at NASA Headquarters, which included participants from the Systems Engineering Leadership Development Program (SELDP). The program took NASA through the halls of the House and Senate, giving them a crash course on the legislative branch of government, covering everything from the budget to the future of U.S. human spaceflight.

Blame Oliver Cromwell

NASA’s introduction to the Hill began with a story by Charles Cushman, professor of political management at George Washington University:

Once upon a time, shortly after the Puritans landed at Plymouth Rock, King Charles I (reign 1625 1649) ruled the United Kingdom. He managed to start and lose a war with Scotland, start and lose a civil war in England, and eventually lose his head in the end. His ultimate antagonist was Oliver Cromwell, leader of the opposing army in the English civil war of 1648. Cromwell, the victor and hero, became the Lord Protector and tyrant of the United Kingdom until his death in 1658.

Over a century later, when the Framers of the Constitution gathered to form a more perfect union, the story of Cromwell’s transformation from hero to tyrant was fresh in their minds. They were terrified of power, and as a result created a form of government best described as a “friction maximization machine.”

American government is meant to be slow and frustrating. Only the agendas with significant support survive, and no single entity or individual has the ability to acquire power quickly enough to pull a Cromwell. It has been said that our federal government is 3% efficient, remarked Cushman, and the Framers might say that our government is 97% tyranny-free.

Bills, Laws, and Power of the Purse

The resulting Constitution created three branches of government: executive, judicial, and legislative. While NASA is positioned under the executive branch, it was created by the legislators in Congress.

Congress passed the National Aeronautics Space Act in 1958, turning the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA) into NASA. The driving force in the Senate behind the Space Act was Majority Leader Lyndon Baines Johnson. Contrary to popular belief, this was not simply a response to the Russians launching Sputnik. As the launch of Explorer I in January 1958 showed, the United States had been preparing to launch its own satellite well before Sputnik.

The transference of military rocket hardware, engineering experts like Wernher von Braun, and facilities like the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Langley Field to NASA, combined with the passage of the National Defense Education Act in 1958 (which pumped money into engineering education) transformed NASA into the agency that would put men on the moon. All of this depended on money from Congress.

NASA’s existence hinges on the support of Congress. Members of the House of Representatives and Senators are elected to represent the needs of their constituents, but they must also balance national needs. After President Kennedy made the moon landing a national priority in the 1960s, NASA received four cents of every dollar in the federal budget. Today it receives just over one-half cent of every tax dollar.

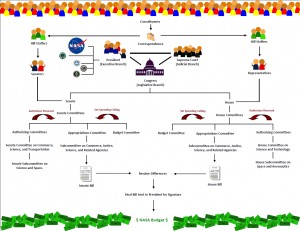

Hill staffers explained the budget process to the SELDP group. Simply put, it begins when the President rolls out the budget request. The White House budget then goes to Congress for authorization and then appropriation. The last two steps must be approved by both Congress and the President. Congress must pass appropriations bills to fund agencies like NASA—although they’re not always done on time, which means using stopgap maneuvers like continuing resolutions to keep things moving until the process is finalized.

The devil is in the details. Authorizing committees pass bills which call for the establishment or renewal of a program or agency. The House and the Senate have their own authorizing committees and subcommittees that pertain to NASA. In the House, the Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics falls under the Committee on Science and Technology. In the Senate, the Subcommittee on Science and Space falls under the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation.

The budget for NASA is proposed by the President and then reviewed by the House and Senate Budget Committees. The budget is finalized once it has gone through the House and Senate Appropriations Committees, committee differences have been resolved, and the President signs the final bill.

Once authorized, appropriations committees are in charge of setting expenditures for discretionary funds. The expenditure ceilings for these committees are set by House and Senate Budget Committees, who see the president’s budget first. Like the authorizing committees, there are appropriations committees for the House and for the Senate that pertain to NASA. The names of the appropriations committees are the same for both the House and Senate: Committee on Appropriations. The subcommittees also have the same name: Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies. Communication between appropriations subcommittees and the agencies they fund is essential. Ultimately, the House and Senate subcommittees play a zero-sum game with limited resources, and have to agree on how to distribute funds among the executive branch departments and agencies.

Another challenge comes from differing timelines. “NASA looks at a lifecycle. We try to plan and manage the unknowns, over a long-term lifecycle,” said Scott Glubke, MESA Division Chief Engineer at Goddard Space Flight Center. “Congress wants to do cut and dry, one year at a time… It’s two totally different systems, speaking two totally different languages.”

SELDP Take-Aways

Knowing how Congress does its job and learning how to work with them is vital to NASA successfully working with them as a partner. This means forming relationships with representatives, senators, and staffers in their home districts, states, and on Capitol Hill. It means project managers talking to program directors at field centers and NASA headquarters so the correct information can effectively travel the six blocks to decision makers on the Hill. It means finding ways to communicate more clearly, eliminating jargon, and speaking a common language. It also means realizing that all American citizens have say in the process.

“Before I went into the course I was pretty ‘civically challenged,’ but I think I certainly benefitted a lot from this,” said Rick Ballard, J-2X Engine SE&I Manager at Marshall Space Flight Center. He noted his rediscovery of the power of writing to Members of Congress to voice opinions. (Each Member and Senator has legislative correspondents, whose sole responsibility is to respond to individual letters and convey constituent concerns to decision makers.) “I do plan on going back to Marshall and telling the people on my team and trying to keep them held together.”

Many SELDP participants said that they would think differently about how to plan and manage their projects and teams now that they better understand the context in which the agency operates. While over the course of the week many voiced frustrations with the Congressional system, they realized that the system is not theirs to fix.

“I started out always being frustrated with Congress and the budget processand I think I came to the conclusion pretty early that everyone that we talked to was completely practical,” said Matt Lemke of the Orion Project Office at Johnson Space Center. Over the course of the week, participants raised many questions concerning ways to solve the problems of government, but, as Lemke discovered, that isn’t that point. “I came to the conclusion days ago that we’re not going to solve those problems. It’s not a problem that is solvable. We need to learn how to live within this chaos.”

When asked how NASA should tell people to support NASA, Goddard Space Flight Center scientist John Mather replied, “[That] isthe challenge of life, isn’t it? How do you explain to the world that the thing you want is the thing we all should want?” This is what NASA must do more effectively through closer relationships with Congress and better communication.

In the end, this is the way our federal government operates. NASA lives and dies by this system. The agency must address the needs of Congress in order to thrive, not the other way around. Don’t like it? Then blame Oliver Cromwell.