February 28, 2011 Vol. 4, Issue 2

The next generation of engineers and managers descended on PM Challenge to share stories and perspectives on professional development, open government, and international collaboration.

Young professionals from NASA, industry, international organizations, and academia participated in impromptu gatherings and formal presentations and panels at PM Challenge to gain insight from aerospace leaders and other young professionals about project management and the role of the next generation in the future of exploration.

In a panel on developing new engineers at NASA, five young professionals shared their thoughts on the importance of rotational development programs, access to and participation in lessons learned forums, career growth opportunities, and the importance of having the chance to fail. Each topic had a common denominator: having a good manager.

Above: From left to right: Sam Miller (Langley Research Center), Theo Muench (Goddard Space Flight Center), Gary Dittemore (Johnson Space Center), Kelly Currin (Kennedy Space Center), and Adam Harding (Dryden Flight Research Center) on a panel about developing new engineers at the 2011 NASA Project Management Challenge. Photo Credit: NASA APPEL

“A manager can make or break these opportunities,” said Gary Dittemore, an integration engineer from Johnson Space Center. Dittemore started his career with nine other young engineers, and he is the only one still at NASA. Often it takes four or five years of experience to figure out whether or not you like your position, he said. Expanding the number of development opportunities like the Systems Engineering Leadership Development Program (SELDP) and exploring alternatives beyond the current options would benefit young professional development and retention, he suggested.

Theo Muench, an aerospace engineer from Goddard Space Flight Center, talked about the need for managers to convey the “why” of project requirements. He recalled working on a project where particles greater than 50 micrometers in size were not allowed on the hardware. He later learned that the requirement originated from an incident where the pressure wave generated by setting a notebook down on a table shattered a component in the system. “It’s really important to know how those golden rules and requirements are communicated to a developing engineer,” he said.

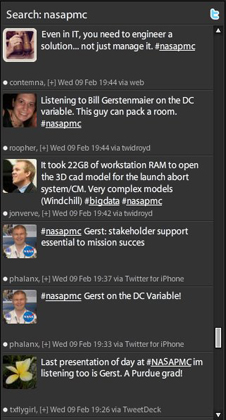

Young professionals kept a running conversation going on Twitter during the two-day Project Management Challenge. Image Credit: NASA APPEL

Muench also touched on the importance of storytelling that he experienced this while working with retired astronaut T.K. Mattingly. He recalled Mattingly telling him a story from his early engineering career. “He told me that story because he wanted to teach me a lesson. I didn’t realize at the time, but essentially he was being a storyteller,” he said. To all the seasoned engineers out there, he added, “You have the experience become a storyteller.”

Kelly Currin, a shuttle engineer from Kennedy Space Center, spoke on the value of “improving our technical training and encouraging rotational assignments.” Managers who encourage involvement in hands-on learning opportunities and make meaningful work available over “check the box” development programs play an important role in retaining young engineers at NASA. Adam Harding, an aerospace engineer from Dryden Flight Research Center, added that establishing informal mentor relationships plays an important role. “Think about the members of your teams,” he said. “Not just the leads, but also the ones in the trenches doing the work. Get to know them.”

Learning through failure is essential to the development of new engineers, said Sam Miller, an electrical engineer from Langley Research Center. “You only have to do that once in a career and [you’ll] never forget it,” he said. “If an engineer can’t fail, you’re not developing them.” When asked how the older generation needs to change in response to the next generation, he replied that large changes are not necessarily needed. “Change the way you interact, not the way you think.”

In another session, Nick Skytland, a project manager at NASA Headquarters, and Lealem Mulugeta, a project engineer from the Universities Space Research Association, spoke about creating a culture of experimentation through NASA’s Open Government Initiative. They emphasized that it’s a process, not a single product. NASA has always been an open organization, as demonstrated by citizen participation, transparency with external stakeholders, partnerships, and efforts to improve internal NASA collaboration and innovation.

A shift is happening, they explained, in which emerging “citizen scientist” organizations are doing real science, engineering, and fundamental technology development. With a public following established, the next step is to develop an open and effective platform that will enable constructive contributions. “First, inspire. Then engage,” Skytland said. (View the presentation.)

The final young professional panel during PM Challenge offered a more international perspective. Gene Bounds, senior vice president for the Project Management Institute, hosted a panel featuring Carole Hedden, special projects editor for Aviation Week; Stacey Edgington, a NASA official who also serves as chair of the workforce development and young professionals committee for the International Astronautical Federation; Justin Kugler, a systems engineer at Johnson Space Center; and Agnieszka Lukaszczyk, chairperson for the Space Generation Advisory Council (SGAC).

Above: From left to right: Eugene Bounds (Project Management Institute), Carole Hedden (Aviation Week), Stacey Edgington (NASA Headquarters), Agnieszka Luakszcyk (Space Generation Advisory Council), and Justin Kugler (Johnson Space Center) discuss developing the international young professional community at the 2011 NASA Project Management Challenge. Photo Credit: NASA APPEL

A 15.7 percent voluntary attrition rate among young professionals across the aerospace industry sparked the 2010 Aviation Week Young Professionals Study, said Hedden. The study found that young professionals rate benefits, technical challenges, opportunities to advance, salary, and stability as most important when choosing a job. Stability in job location and the ability to start a family were overarching drivers for job selection. Young professionals leave the industry because of poor relationships with direct supervisors, lack of flexibility, lack of variety of in daily work, lack of inclusion of ideas and contributions, and limited opportunities to learn new skills.

Hedden announced the initiation of a 20-year longitudinal study tracking industry young professionals. She looks forward to future research that will provide more international perspectives and insights about what information young professionals find is best transferred through specific media channels.

Kugler, an engineer who is a member of the newly formed NASA Forward organization, works to facilitate International Space Station research through non-traditional partners. He emphasized the importance of better articulating a vision of space exploration to NASA’s stakeholders. He noted that his sister is an anthropologist. “What does space exploration mean to her? What about the kids that want to go work for Google or in biotech?” he asked. “We’ve struggled in some ways to articulate why what we do is important to everybody else.”

Edgington shared her observations of young international professionals. She commented on her surprise when a young Korean engineer approached her at the International Astronautical Congress (IAC) last year and asked, “Can you tell me more about young professionals? We don’t have such a thing in Korea.” Not all young professionals self-identify, she said. She also noted that young professionals from United States tend to be much more outspoken, while those from other countries are more concerned with becoming a part of their company or agency. English language skills significantly affect involvement in international space activities. Edgington is looking for new ways to increase young professional involvement in the IAC.

Lukaszczyk, chairperson for SGAC, a volunteer organization consisting of over 4,000 members in over 90 countries, presented the challenges her organization faces. Obstacles like poverty, gender bias, access to technology, and lack of collaboration pose great obstacles for international space participation. “It’s difficult,” she said. “You have to prove yourself.” She has had the opportunity to enable bright, young people without resources to get involved in space. “You see the worth of your work immediately when you look at these people.” Her goal, she said, is to leave the door of opportunity open just a bit wider than it was before.