By ASK Editorial Staff

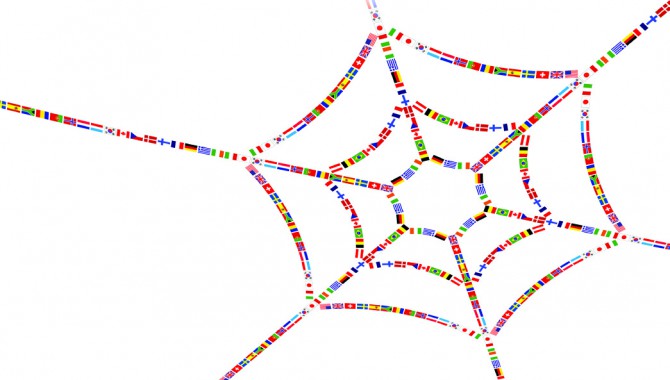

In March 2011, some two dozen representatives from space agencies and related organizations around the world meet in the top-floor conference room of the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Paris headquarters. Outside the windows lining one wall, flags representing ESA’s nineteen member nations stir in the breeze. A painting of two human figures floating on a background of stars and galactic dust—an image of space exploration—hangs at one end of the room. Space exploration is why the members of the International Project Management Committee (IPMC) have gathered here. The group meets twice a year to develop ways to share the project management expertise that successful space programs depend on.

The space agencies of Germany, France, Italy, Czech Republic, Canada, South Korea, South Africa, and the United States are represented. Committee members from JAXA, the Japanese space agency, have sent their regrets; the aftereffects of the recent devastating tsunami have kept them home. Ed Hoffman, director of NASA’s Academy for Program/Project and Engineering Leadership, chairs the meeting.

The committee is just over a year old. Prior to NASA’s 2010 Project Management (PM) Challenge in Galveston, Texas, Hoffman asked Lewis Peach to help bring the international space community together. The result was two days of panels at the PM Challenge featuring senior leaders from space agencies around the world and focusing on multinational aerospace projects. Participants in that international track stayed an extra half day to explore the possibility of forming the committee that became the IPMC.

The value of such a committee was clear to Hoffman and the others at that meeting. International collaboration on aerospace projects is increasingly the norm. Most efforts today are multinational, bringing together space agencies, universities, and industries from around the world. And carrying out ambitious and expensive future science and exploration missions will undoubtedly require the resources of many nations. Those missions will demand that all the partners involved possess high-level project management and collaborative skills. An international committee focused on sharing the collective project management knowledge of many space agencies could help make that expertise widely available and build some of the relationships that collaboration depends on.

Bettina Böhm, head of human resources for ESA and now vice-chair of the IPMC, explains ESA’s interest in the committee, noting that the need to collaborate with others is becoming more and more important and that, at the time of that first, exploratory meeting, ESA had just carried out a study on new and better ways to prepare people for program and project management. Bringing experienced people together to share practical learning was clearly one valuable approach.

At that initial meeting, the group established some foundational norms, namely, inclusiveness, mutual respect, and the need to show practical benefits.

The IPMC had its first official meeting a month after the 2010 PM Challenge in conjunction with the International Astronautical Federation’s (IAF) spring meeting in Paris. It became an IAF Administrative Committee. That official link with IAF’s more than two hundred organizations that are active in space in nearly sixty countries gives the committee visibility and the potential for widespread influence. IPMC meetings since have been coordinated with IAF events: the International Astronautical Conference in Prague in the fall of 2010 and now in Paris again, where the IAF was holding its sixtieth-anniversary celebration and planning for the next conference.

The value of such a committee was clear to Hoffman and the others at that meeting. International collaboration on aerospace projects is increasingly the norm. Most efforts today are multinational, bringing together space agencies, universities, and industries from around the world.

Böhm says these early meetings have been mainly—and appropriately—devoted to developing relationships, and creating and maintaining trust and openness. There have been some concrete actions taken, though. The most ambitious so far is the International Project Management course held at Kennedy Space Center in early 2011. Participants in the five-day course included fifteen people from ten IPMC agencies and organizations. At this Paris committee meeting, Andrea Cotellessa, an ESA staff member who attended the course, describes his experience. His review is positive (as were the assessments of other attendees), but he does suggest that some of the sessions were too much from a NASA point of view, with little attention to the different experiences of other agencies. The committee discussed ways of bringing more cases and lessons from other agencies into the curriculum. The second International Project Management course at Kennedy was held in July.

The committee has also recognized the importance of reaching out to young professionals—the engineers, managers, and scientists starting their careers—who will have the privilege of shaping international space-exploration missions over the next several decades and will face the challenges of those ambitious space programs. Young professionals have been invited to the meetings as observers, and the committee is considering a proposal for a young-professionals workshop and young-professional membership.

Emphasizing the need for continuing action, Böhm suggests that at least a couple of hours of every future meeting should focus on an issue in a way that results in specific, useful activity. Her emphasis on concrete action resonates with other members of the committee, who know that the benefits they can bring to their organizations justify their investments of time and travel.

The committee’s key challenge, says Hoffman, is to learn how to share the right expertise in the right ways among agencies that differ in size, experience, and how they approach aspects of the work. Continuing activities and conversation among members, like Cotellessa’s International Project Management course critique, are helping to develop a fuller understanding of member agencies’ practices, which will make effective learning possible at future International Project Management courses and in other settings.

Another challenge is how to keep committee members who are scattered around the globe productively connected, given that they meet formally only twice a year.

That seems to be happening. Relationships formed here are proving to be the foundation for gatherings of small groups to work on issues of specific concern to their agencies. For instance, DLR, the Germany Aerospace Center, brought practitioners of several space agencies together at a small PM Challenge–like event, something unlikely to have happened without DLR’s participation in NASA’s PM Challenge and connections developed through the IPMC.

The committee will meet next at the International Astronautical Conference in Capetown in October. It is still very much at the beginning of its efforts. Its contribution to building the knowledge and networks to support twenty-firstcentury space exploration will no doubt take a variety of forms, likely including joint conferences and courses and a range of collaborative initiatives that arise from members’ discussions of their shared concerns and challenges. It is not possible to say exactly where its commitment to inclusiveness, respect, and the pursuit of practical benefits will take the IPMC, but it hopes to have a significant role in improving international aerospace learning and cooperation.