President John F. Kennedy in his historic message to a joint session of the Congress, on May 25, 1961 declared, "...I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth." Photo Credit: NASA

January 26, 2012: Volume 5, Issue 1

Landing a man on the moon and safely returning him to Earth before the end of the decade came down to choosing the best strategy.

President John F. Kennedy in his historic message to a joint session of the Congress, on May 25, 1961 declared, “…I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

Photo Credit: NASA

Even before President Kennedy made his speech to a joint session of Congress in May 1961 announcing the decision to go to the moon before the end of the decade, engineers and scientists were already thinking about the challenge. The President’s goal turned up the pressure to transform visions of a round-trip lunar mission into reality. It was evident that path ahead would be expensive, challenging, rewarding, and dangerous.

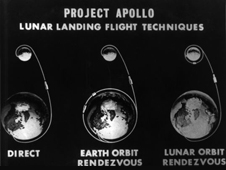

In terms of actual rocket engineering, there were three competing approaches to get to the moon:

- Direct Ascent – blast straight off the ground on a direct path to the lunar surface and return the same way;

- Earth-Orbit Rendezvous (EOR) – launch two rockets into Earth orbit, refuel and assemble the spacecraft, and then take the entire craft to the moon;

- Lunar-Orbit Rendezvous (LOR) – launch one rocket towards lunar orbit and land a small lander on the lunar surface while the remaining spacecraft stayed in orbit.

The initial favorite, direct ascent, posed several challenges. The approach relied on the construction of a twelve-million-pound-thrust, battleship-sized Nova rocket that would take nearly a decade, if not longer, to construct. Second, the rocket was projected to be so powerful that it could not launch from Cape Canaveral. (NASA looked into launching from hollowed-out cliffs in Hawaii.) Third, astronauts would have to somehow back the large Nova vehicle onto the surface of the moon. Lastly, the moon did not offer a launch pad back for the journey home. Direct ascent was eliminated from the running.

The three principal contending lunar landing techniques: direct ascent (left), Earth-orbit rendezvous (center), and lunar-orbit rendezvous (right).

Image Credit: NASA

This left EOR and LOR. “Kennedy basically boxed NASA in on schedule and performance,” said Steve Garber, a policy analyst in NASA’s History Program Office. “We had flexibility on cost, but we also had flexibility in terms of how we would achieve the goal from an engineering standpoint.”

EOR was the comfortable approach. It was the stuff of Wernher von Braun’s dreams: Earth, low-Earth orbit, moon. However, there wasn’t a clear concept of how to land a large vehicle on the unknown surface of the moon and then propel it from the lunar surface back to Earth. “We didn’t want to put a lot of mass on the moon because then you’d have to lift if all up again,” explained NASA Chief Historian Bill Barry.

LOR was the “dark horse.” It required less fuel and less technology development, and could be accomplished with the proposed Saturn V, which was considerably smaller than the Nova. It employed a small lunar lander, and each of the modules could be tailored independently. The drawback was that LOR didn’t offer a crew rescue option if the tricky lunar rendezvous failed. The possibility of stranding three astronauts 240,000 miles from home was not pleasant to consider.

Both approaches relied on a rendezvous, and trade studies changed the common perception about lunar rendezvous, indicating that a rendezvous around the moon might not be as dangerous as initially thought.

To a certain extent, according to Barry and Garber, the strong cultures of NASA’s centers shaped preferences for each of the approaches. Marshall Space Flight Center favored EOR since it involved constructing lots of rockets. The then-Manned Spacecraft Center (now Johnson Space Center) eventually favored LOR because it meant there would be more spacecraft to develop and build. The agency was of two minds. Deciding between the approaches would come down to determining which offered a strategy that was more feasible and less complex. Which obstacle was NASA willing and able to overcome: landing more mass on the moon or a risky lunar rendezvous?

On June 7, 1962, at the Lunar Mode Decision Conference Marshall representatives spent six hours presenting their argument for EOR. At the end of the day-long meeting, after months of steadfastness, von Braun stood up and read from a sheet of paper he had been scribbling on over the course of the day:

NASA announced the decision to pursue the lunar-orbit-rendezvous strategy at a press conference on July 11, 1962. At the conference table, left to right above, are NASA Administrator James E. Webb, Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., Office of Manned Space Flight Director D. Brainerd Holms, and OMSF Director of Systems Joseph F. Shea.

Photo Credit: NASA

We at the Marshall Space Flight Center readily admit that when first exposed to the proposal of the Lunar Orbit Rendezvous Mode we were a bit skeptical—particularly of the aspect of having the astronauts execute a complicated rendezvous maneuver at a distance of 240,000 miles from the earth where any rescue possibility appeared remote. In the meantime, however, we have spent a great deal of time and effort studying the [three] modes, and we have come to the conclusion that this particular disadvantage is far outweighed by [its] advantages.

We understand that the Manned Spacecraft Center was also quite skeptical at first when John Houbolt advanced the proposal of the Lunar Orbit Rendezvous Mode, and that it took them quite a while to substantiate the feasibility of the method and fully endorse it.

Against this background it can, therefore, be concluded that the issue of “invented here” versus “not invented here” does not apply to either the Manned Spacecraft Center or the Marshall Space Flight Center; that both Centers have actually embraced a scheme suggested by a third source….I consider it fortunate indeed for the Manned Lunar Landing Program that both Centers, after much soul searching, have come to the identical solutions.

In the weeks that followed, the final decision to go to the moon using the LOR approach made its way to the desk of Administrator James Webb (a proponent of the direct ascent approach). On June 22, 1962, the Manned Space Flight Management Council announced in favor of the LOR approach.

Starting July 16, 1969, NASA flew eight missions to the lunar surface, and although Apollo 13 didn’t land on the moon, all the astronauts made it home safely.

Read about John Houbolt and the genesis of the lunar-orbit rendezvous concept in Enchanted Rendezvous by James Hansen.