By Roger Forsgren

Like most people, project managers and engineers may have an interest in history without realizing that understanding the past can help them better understand and manage the present. Studying the past can be an opportunity to see how leaders overcame daunting obstacles to achieve their goals.

Portrait of Abraham Lincoln.

Image Credit: Alexander Gardner/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

We use recent history to guide our work. A doctor relies on a patients history to chart future care, a lawyer reviews precedent to make a solid case, and an engineer studies a failure report or participates in a mishap review to improve a design.

Although economic, political, and cultural landscapes evolve over time, human nature remains the same. So history can shed light on how people act and react, how they win and lose, and how they lead others to do great things. As Niccolo Machiavelli noted, “Whoever wishes to foresee the future must consult the past; for human events ever resemble those of preceding times. This arises from the fact that they are produced by men who ever have been, and ever shall be, animated by the same passions, and thus they necessarily have the same results.”

Even though he lived one hundred and fifty years ago, we can still learn from the actions of an extraordinary leader: Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln lived in a fragile new nation that struggled with the dichotomy of its revolutionary pronouncement that all “men are created equal” while millions of men and women remained in bondage. He fought to sustain the democratic dream by preserving the Union and eventually freeing the slaves. His actions completed the American Revolution and finally fulfilled the promise of the Founding Fathers.

Lincoln had little political experience before becoming president, serving only one term as a congressman from Illinois, then losing the race for the U.S. Senate seat from Illinois to Stephen Douglas. His remarkable performance in debates with Douglas brought him national attention and paved the way to his nomination for the presidency from the newly formed Republican Party. Lincoln wasn’t even on the ballot in nine of the southern states and won the presidency in 1860 with barely 40 percent of the popular vote. Before he was inaugurated, seven southern states seceded from the Union.

By using a straightforward and honest approach, Lincoln repulsed an attack upon his constitutional powers by the Radical Republicans without antagonizing his accusers and without further fragmenting his delicate political position as president.

To the political professionals of both the Democratic and Republican parties, Lincoln appeared to be a country bumpkin woefully unprepared to tackle the question of slavery. He found himself dealing with the essential question inherent in the idea of a republic: can democracy survive partisanship and regional interests? The rebellion of the southern states seemed to confirm what the repressive monarchies of Europe had thought all along: that America’s democratic experiment was naïve and destined for failure. Human nature was meant to be contained and controlled, not set free.

Lincoln understood human nature better than the career politicians who were dismissing him before he made the train journey to Washington for his inauguration. He knew he had to form a unified government to deal with the national crisis and selected cabinet members who would not only represent the interests of various states whose support he considered essential, but who were also in his opinion the most qualified to help him succeed. In doing so, he reached out to several former political opponents that had run against him for the Republican nomination.

William Henry Seward, the eminent senator from New York, had been considered the front-runner for the nomination but couldn’t gather sufficient support from the most radical wing of the Republican Party to gain the nomination. Seward was the career politician who understood how Washington worked. He considered the new president inexperienced and ill prepared for the job that confronted him; furthermore, he assumed his appointment as secretary of state meant that Lincoln would cede presidential authority to him. A few months into the new administration, Seward realized he was mistaken. He learned to enjoy the president’s down-home, straightforward style and admired the president’s keen mind. In February of 1862, Seward watched his president and now friend remain steadfast to the cause and his work even as his son, Willie, died of tuberculosis in the White House. Rather than feeling animosity toward Lincoln for winning the nomination, he felt a kinship to this man who suffered so much in order to keep the Union together.

Salmon P. Chase had served as governor of Ohio and had recently been elected to the Senate. Lincoln needed the support of Ohio and also knew that Chase had a brilliant mind and was an accomplished administrator. Lincoln appointed Chase his secretary of the Treasury. The politically ambitious Chase was dumbfounded that he had lost to the backwater candidate from Illinois. Chase disdained Lincoln’s unrefined and unpretentious style and never fully respected Lincoln’s leadership.

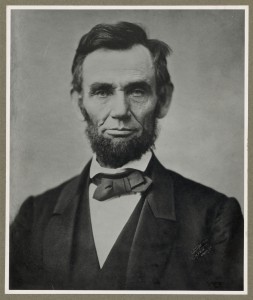

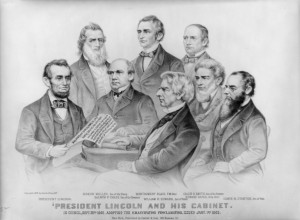

President Lincoln and his cabinet in council, September 22, 1862, adopting the Emancipation Proclamation.

Image Credit: Published by Currier & Ives/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

By December 1862, the Civil War had dragged on for nearly two bloody years. The Union Army took a crushing blow from Robert E. Lees Army of Northern Virginia at the Battle of Fredericksburg. As the endless procession of Union casualties were being carried back to Washington, Lincoln said, “If there is a place worse than hell, I am in it.”

Not only was the Union split, but the North itself was fracturing into two irreconcilable camps: the Democratic Copperheads, who wanted to make peace with the South and allow them to secede, and the Radical Republicans, who wanted immediate emancipation of the slaves and were in open revolt against what they saw as Lincoln’s mismanagement of the war effort. As the Copperheads began demanding an end to the killing, the Radical Republicans, furious over the Union defeat at Fredericksburg, began congressional hearings over the conduct of the war.

A lifelong abolitionist, Chase held close ties to the Radical Republicans and had been telling them for months that the North’s misfortune was due to Seward’s influence over Lincoln. He reinforced the idea that Lincoln was in over his head. Seward, he claimed, was not only leading the Union to defeat but was also responsible for Lincolns protracted inaction in freeing the slaves.

The Radical Republicans began to demand Seward’s resignation. In reality, Lincoln’s primary concern was saving the democratic ideals of the nation by preserving the Union. To achieve that end, he was even willing to allow slavery to remain in the South as long as the southern states stayed in the Union and agreed not to let slavery spread. Lincoln hated slavery but believed it would naturally decline as economic forces made it unprofitable. He also found himself walking a political tightrope over the issue of emancipation because many of his own northern troops enlisted not to free the slaves but to keep the Union intact. Furthermore, Lincoln had to consider the crucial role played by the border states of Kentucky and Maryland. Either state might easily side with the South if they concluded that Lincoln was waging a war only to free the slaves. Had Maryland sided with the South, Washington, D.C., would

have been surrounded by hostile territory.

With Chase’s scheming and intrigue egging them on, a majority of Republican senators demanded Seward’s removal and a reorganization of Lincoln’s cabinet. Rumors soon swept the capital that the cabinet was going to resign and that the president himself had decided to resign. Lincoln understood that the Radical Republicans were attempting to usurp his executive powers and were determined to take control of the war effort away from the duly elected commander in chief. He also knew that the political intrigue aimed at him was fostered by his own Treasury secretary.

The president, who had faced turmoil and derision since his election and had watched helplessly as his generals, through incompetence or refusing his orders, allowed the northern armies to be humiliated by smaller rebel forces, now faced the biggest test of his political power. As he revealed to a friend, “What do these men want? They wish to get rid of me, and I am sometimes half disposed to gratify them.” Lincoln continued, “Since I heard last night of the proceedings of the caucus, I have been more distressed than by any event in my life … We are now on the brink of destruction. It appears to me that the Almighty is against us, and I can hardly see any ray of hope.”

Seward offered Lincoln his resignation, hoping that might defuse the situation.

When a group of Republican senators arrived at the White House, Lincoln heard their complaints against Seward and their insistence that the war was being lost because of the secretary’s influence on the presidents decisions. Lincoln listened politely and then told the senators that he would take their advice under consideration. He invited them back to the White House for a second meeting the next day.

When they arrived the following day, they were surprised to be ushered into the room where the entire cabinet was seated. The cabinet members, including both Seward and Chase, were shocked to see the senators enter the room. Lincoln asked the senators to state their grievances in front of his cabinet. They boldly repeated that the war was being mismanaged because Lincoln had failed to listen to the advice of his entire cabinet and was being manipulated and controlled by Seward.

Lincoln responded to the charges by stating that he listened to and thought carefully about any recommendation given to him by his cabinet ministers and, although he relied on their opinions, it was he alone who made the final decision. Lincoln then turned to his cabinet and asked each one of them to state publicly if they agreed with his statement. All eyes were fixed on Chase. The secretary of the Treasury squirmed in his chair before admitting that he agreed with the president’s statement but added, in a feeble attempt to save face, that he wished major decisions could be more thoroughly discussed in the cabinet. The senators angrily left the White House, thoroughly disgusted with Chase’s inability to stand up in public to those he accused in private.

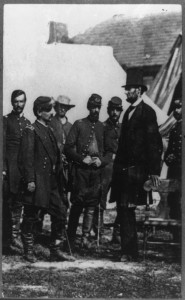

Abraham Lincoln on the battlefield at Antietam, Maryland, October 3, 1862.

Image Credit: Alexander Gardner/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The next morning a humiliated and chagrined Chase arrived at the White House with his letter of resignation. He told the president that the previous day’s meeting had been a “total surprise” to him and that he “had been painfully affected by the meeting.” Lincoln anxiously grabbed the document from Chase, who seemed surprised at the president’s apparent eagerness to accept it.

The following day Lincoln informed both Seward and Chase that he would not accept their resignations. Lincoln never had any intention of accepting Seward’s resignation. As for Chase, Lincoln hoped his lesson in humility would chasten his secretary of the Treasury because the president recognized Chase’s ability and skill to keep the war effort funded. Lincoln wrote in his response to Chase that it was in the “public interest” that he remain at his post at Treasury and that he would not accept his resignation.

By using a straightforward and honest approach, Lincoln repulsed an attack upon his constitutional powers by the Radical Republicans without antagonizing his accusers and without further fragmenting his delicate political position as president.

Trying to lead in such desperate times meant that Lincoln had to gain the support and help of factions that he may not have agreed with. Lincoln needed the support of the Radical Republicans in Congress and also needed the expertise of his scheming secretary of the Treasury to hold the Union together. He was willing to take abuse and criticism as long as he controlled the situation and could move people and events toward a successful conclusion of the war and the preservation of the Union.

Lincoln’s pragmatic approach to an insubordinate cabinet minister and the Radical Republicans managed to defuse a potential constitutional crisis concerning presidential authority, which would have subordinated his powers as president and commander in chief to a congressional caucus. Lincoln certainly faced bigger and more trying circumstances in his presidency, but this episode shows his brilliance in manipulating a dangerous situation to his advantage.

What lessons does this story offer to today’s leaders and project managers? Here are a few of the important ones:

- Keep your eye on the ultimate goal and make decisions that will help you achieve it. Don’t let your personal feelings or those of your team stand in the way.

- Favor open communication. Openness about what has been happening behind the scenes is a powerful tool.

- Don’t be in a hurry to eliminate talented but difficult people. There may be ways to win their cooperation.

Note: The story of Lincoln’s cabinet crisis comes from Doris Kearns Goodwin’s excellent book, Team of Rivals.

About the Author

|

Roger Forsgren is the deputy director of the NASA Academy of Program/Project and Engineering Leadership. He is responsible for the contractual and financial management of the entire Academy program, and has recently been responsible for developing new engineering courses that focus on foundational learning of NASA-specific engineering and space sciences; creative thinking and innovative engineering methodologies; and leveraging of invaluable knowledge from historical NASA lessons learned. |

More Articles by Roger Forsgren

- Practices: The Innovation Report The ICB: Recognizing and Rewarding Innovation (ASK 22)