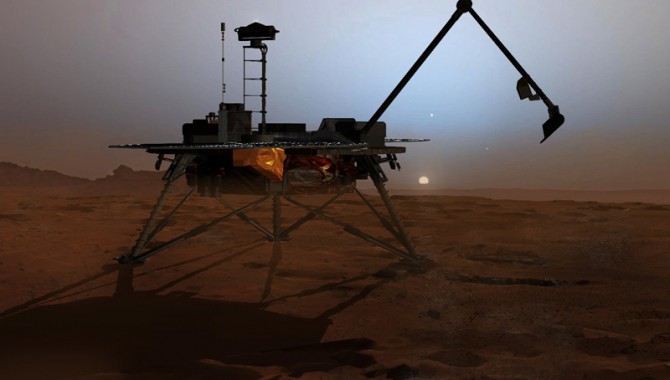

In this artist's concept illustration, NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander begins to shut down operations as winter sets in. The far-northern latitudes on Mars experience no sunlight during winter. This will mark the end of the mission because the solar panels can no longer charge the batteries on the lander. Frost covering the region as the atmosphere cools will bury the lander in ice. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

June 29, 2012 — Vol. 5, Issue 6

Effectively telling the story of a NASA mission means connecting the audience, the storyteller, and the project team in a conversation.

For the past decade, Veronica McGregor has managed news and, more recently, social media for missions at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. She was the voice behind the Mars Phoenix Lander, the Mars Exploration Rovers, and eventually the Curiosity mission. ASK the Academy caught up with her to gain insights about how project teams can tell the story of their missions through social media.For the past decade, Veronica McGregor has managed news and, more recently, social media for missions at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. She was the voice behind the Mars Phoenix Lander, the Mars Exploration Rovers, and eventually the Curiosity mission. ASK the Academy caught up with her to gain insights about how project teams can tell the story of their missions through social media.

ASK the Academy (ATA): You made an impact on the way a missions story got told using social media on the Mars Phoenix Lander mission, specifically through Twitter. Can you tell us how that came about?

Veronica McGregor: We started the [Twitter] account in May 2008, about three weeks before the mission was going to land. The mission was landing on the Sunday of Memorial Day weekend at 5:00 in the evening, and we knew people weren’t going to be sitting at home watching the news. We were looking for a way that we could put out the story so that people could get it on their mobile devices. It was an experiment.

Few people were using Twitter back then. I started doing different things with the account to see how people would react to it, and it evolved. I found that people responded [better] to the account if it was posted in the first person, as if it were the lander talking. Part of [the benefit to] that was that Twitter limits you to 140 characters and by using the first person it meant I could remove a lot of characters from the post. I also looked at other accounts on Twitter to see how they were posting and I found that most of them sounded like press release headlines. The accounts that were fun to follow were the accounts that were stating facts in the first person. So we adopted the first person for the mission. In the summer of 2008, when that mission was active, it was the fifth most followed account on Twitter. (Barack Obama had the number one account at the time.) Even the Twitter founders said it was one of their favorite accounts. It was one of these unexpected ways they found that people were using Twitter.

ATA: How did you see the interaction between the mission and those following the mission story begin to change?

McGregor: We were posting updates to the mission, I tweeted the landing, and then I started tweeting what the spacecraft what doing every day of the mission. There were two major lessons that came out of that account. One was that there were number of people who wrote back and said that it was the first time they had been able to follow a NASA mission day by day and they had no idea what took place daily on a NASA mission. Most people are only used to reading about a mission when it launches or when it fails.

They were learning from the Twitter account that there were three shifts working 24 hours a day on [the Phoenix] mission. You had a science team analyzing data. They were working with the engineers to develop the next day’s activities and what the lander would do the next day, whether it would dig or whether it would be baking samples. We had the software team coming in and writing the commands so those activities could take place, and then the cycle started all over again when the scientists looked at the new data coming in. People had no idea that that’s what took place daily on a mission.

There were many unexpected results from our Twitter experiment. Followers loved the tweets coming out of the account, but for me the story was the responses that I was getting back. It was just amazing. I received questions from classrooms. I got replies from people of all ages comparing the excitement of the mission to the Apollo missions. It was really then that we realized there was an untapped audience out there of real space fans, what is now in some aspects the Space Tweeps Society. We could see many people, who were responding frequently or asking questions, started connecting up with each other via social media until they formed this community today of people who are very passionate about space and still in touch with each other.

ATA: And the second observation?

McGregor: The second thing was: that was the summer that many reporters discovered news was getting out around them. When the Phoenix mission found ice on Mars, the tweet [to announce it] went out at the exact same second the news release was posted to nasa.gov. A reporter friend of mine commented later that she realized then that NASA had a new way to release news outside of the old “news release” model. A lot of reporters joined Twitter around that time and started following our accounts. Today, I see many stories that we tweet get picked up by reporters, whether we’ve done a formal news release or not. But if we had put the same information in a news release, they may not have done the story. Because we are now able to effectively deliver information to the public directly, its changed the way the reporters look at what story they’re going to write about. It turned things around in terms of the flow of information.

NASA Administrator Charles Bolden speaks to NASA Twitter followers prior to the launch of the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), Saturday, Nov. 26, 2011, at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla. NASA began a historic voyage to Mars with the launch of the car-sized rover which lifted off at 10:02 a.m. EST. The mission will pioneer precision landing technology and a sky-crane touchdown to place Curiosity near the foot of a mountain inside Gale Crater on Aug. 6, 2012.

Photo Credit: NASA/Paul E. Alers

ATA: The success that you had with Phoenix led to social media strategies for the Mars Exploration Rovers and also Curiosity. How do you typically interface with project teams to tell the story?

McGregor: We started Curiosity back in 2009 when the rover was under construction. Its being done in almost the same way that Phoenix was, in the first person. Were getting a lot of great feedback from people. Its at over 100,000 followers on Twitter right now and it also has a Facebook account. We answer a lot of questions from people and well be tweeting the landing for that one as well.

It was really important to me when I started the Phoenix account that people knew I wasn’t just some PR person trying to put a spin on things. I was taking in a lot of questions and emailing them to people on the team: for example, the engineer who was controlling the arm and digging, the software code writer, the mission manager, or one of the scientists. I was forwarding a lot of the questions to them and they would write back to me with answers, which I would then have to condense into 140 characters and post.

I also listened to the mission telecons. I would be on the line, take notes, and then I would tweet interesting updates that came out of those meetings. Of course, there is a fine line between not tweeting news that should go out into a news release first. Since I was also involved in the process of writing news releases, I knew exactly when a news release was going to be issued. So the very second that a news release was issued, I could hit the send button on the tweet.

ATA: How have project teams responded to this form of storytelling?

McGregor: We get different kinds of reactions from the missions and projects. Some projects are more attuned to whats going on in social media and how news travels these days. We often provide advice to missions that want to be involved in social media and appoint someone on their team to tweet or post to Facebook. We’ve found that most people underestimate the time commitment that’s required.

I remember starting the Phoenix account and thinking it would only take five minutes a day because I thought I would only be pushing out information. I didn’t expect the number of questions and responses that came in, and when you get those, you really are obligated to answer. It turned into hours a day. That’s one thing project managers need to be aware of: We have to respond to people, you can’t make it a one-way street.

I can think of only a few cases in which scientists are engaging in social media first hand on their missions. One issue is, at the time they’re needed most to do postings is when the mission is the busiest and that’s when they have the least amount of time. There are some people who tweet when their missions aren’t particularly overwhelming. If you don’t have a team member you can dedicate to do social media at least a few hours a week, then that’s what our office is here to do.

Another thing is that project managers sometimes aren’t aware of how their mission team members are using social media. It’s definitely a different world out there. If any part of what you’re doing is public, you just have to expect that it’s going to be in social media very, very quickly. It’s very important to understanding the flow of information and the speed at which it happens.

ATA: What contributes to effectively telling a project story through social media?

McGregor: Good lines of communication and finding mission team members who are willing and accessible—and many of them are. A lot of them realize its too much work to manage the social media accounts on their own, but if we can email them a list of questions and not overwhelm them and split them up among different members of the team, they’re more than happy to write down some quick answers and get back to us.

ATA: Twitter aside, what other types of social media have you used to tell a project story?

McGregor: We have Facebook accounts for several of our missions. Whenever we get a really great answer back from the team, we’ll post it in its entirety on Facebook (on Twitter we run into the character limitations) and mention, for example, “This response comes from Scott Maxwell, who is a rover driver,” so people know exactly where the information is coming from.

We’ve used USTREAM a lot as well. During the time the Curiosity rover was being built, we had a camera in the clean room that provided a 24/7 live feed and then 2 or 3 hours a day, Monday through Friday, we would open the chat box and do moderated chats. We would also invite mission team members to join us occasionally to be on the chat to answer people’s questions. That worked really well. There are so many things that can be done in social media. Now you’ve got Google+ Hangouts as well.

ATA: What, if anything, has surprised you throughout your experience in communicating NASA missions using social media?

McGregor: The biggest surprise was how well the daily updates were received by the followers. There were a couple of times with the Phoenix mission when the arm was unable to put soil into science instrument where samples were baked and analyzed. The soil was clumpier than they expected and they were having trouble breaking it down into small enough grains so it would enter. If we weren’t tweeting the progress of that challenge each day, people probably would have seen news stories saying the mission was in trouble and they’d have a different sense of what was going on. But since were able to keep people updated on a day-to-day basis about how the team was responding to these challenges and creating fixes, we saw a swell of support from our followers. The responses we received were cheering on the team. The best part was seeing people were getting a true understanding of the complexities and difficulties of the mission, and an appreciation for the amazing engineering and science thought that goes into missions like this.

Also, sometimes we would get a string of questions from people and we’d realize that we weren’t doing a good job at explaining certain things. Mostly that happened in cases where we assumed the public already knew a certain detail or fact. The result of that assumption is we’d get questions or comments from people questioning why the mission did something a certain way.

It came up a lot with questions and comments about the cameras. They’d write, “We paid millions of dollars for this mission and it has a black and white camera?” We didn’t realize that we needed to explain to people ahead of time that the very first images to come back from the [Phoenix] mission would be in black and white and that the mission did have color filters. The first pictures that came back from Mars were of the spacecraft itself and not of Mars and people thought that was a mistake. We realized that we needed to do a better job at telling people that the first images to come down are strictly for the engineers to know whether the spacecraft is in good health.

This feedback from the public was great. Once we saw there was a misunderstanding about any part of the mission we would respond on Twitter, but we would also incorporate the information into the next news release.

That type of feedback didn’t exist before and today it happens immediately. It’s fantastic.

NASA Administrator Charles Bolden, center, joins about 150 NASA Twitter followers near the launch clock prior to the launch of the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), Saturday, Nov. 26, 2011, at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla. NASA began a historic voyage to Mars with the launch of the car-sized rover which lifted off at 10:02 a.m. EST. The mission will pioneer precision landing technology and a sky-crane touchdown to place Curiosity near the foot of a mountain inside Gale Crater on Aug. 6, 2012.

Photo Credit: NASA/ Paul E. Alers

n this artist’s concept illustration, NASA’s Phoenix Mars Lander begins to shut down operations as winter sets in. The far-northern latitudes on Mars experience no sunlight during winter. This will mark the end of the mission because the solar panels can no longer charge the batteries on the lander. Frost covering the region as the atmosphere cools will bury the lander in ice.

Featured Photo Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona