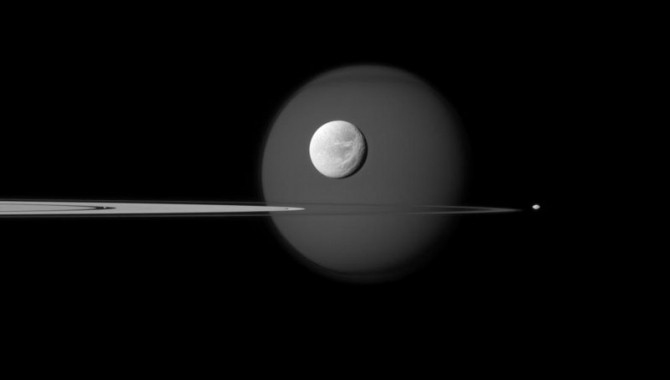

Saturn's largest moon, Titan, is in the background of the image, and the moon's north polar hood is clearly visible. See PIA08137 to learn more about that feature on Titan (3,200 miles, or 5,150 kilometers across). Next, the wispy terrain on the trailing hemisphere of Dione (698 miles, or 1,123 kilometers across) can be seen on that moon which appears just above the rings at the center of the image. See PIA10560 and PIA06163 to learn more about Dione's wisps. Saturn's small moon Pandora (50 miles, or 81 kilometers across) orbits beyond the rings on the right of the image. Finally, Pan (17 miles, or 28 kilometers across) can be seen in the Encke Gap of the A ring on the left of the image. The image was taken in visible blue light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Sept. 17, 2011. Photo Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

July 31, 2012 Vol. 5, Issue 7

The year was 1993—and something wasn’t right.

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, is in the background of the image, and the moon’s north polar hood is clearly visible. See PIA08137 to learn more about that feature on Titan (3,200 miles, or 5,150 kilometers across). Next, the wispy terrain on the trailing hemisphere of Dione (698 miles, or 1,123 kilometers across) can be seen on that moon which appears just above the rings at the center of the image. See PIA10560 and PIA06163 to learn more about Dione’s wisps. Saturn’s small moon Pandora (50 miles, or 81 kilometers across) orbits beyond the rings on the right of the image. Finally, Pan (17 miles, or 28 kilometers across) can be seen in the Encke Gap of the A ring on the left of the image.

The image was taken in visible blue light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Sept. 17, 2011.

Photo Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Each time I revisit the story of the Cassini project, I am impressed by their success. With 260 scientists from 17 countries spanning 10 time zones on the science team, 4 years, and $200 million to design and fly the spacecraft and its 18 instruments, project scientist Dennis Matson had quite a challenge. As a flagship mission, the team was hyper-aware of increased resource demand and runaway cost and lacked confidence in the cost reserves paradigm to manage them. Any false move could cancel the project.

Instead, the instrument team adopted a market-based approach they called the Cassini Resource Exchange, where they could trade data rate, budget, mass, and power among themselves using an online system. The “Casino Mission” as it came to be known, used a free-market mechanism to deliver all 18 planned instruments successfully.

The system was an innovative and risky move for the Cassini team that paid off with an overall increase in the science payload cost of less than one percent and a decrease in science payload mass by seven percent. As two Cassini team members once wrote in an ASK Magazine story, “It’s amazing what you can do when you don’t have a choice.”

The Cassini team had no choice but to adopt a different approach.

In the fifteen years since its launch, I have asked John Casani, who worked on Cassini, why the ‘casino’ methodology has been used rarely, if ever, on other projects. He replied, “Ed, project managers don’t want to give up control.” I haven’t known how to respond except with a knowing nod.

Now the year is 2012, and something still doesn’t feel quite right. Casani’s response still gnaws at me. Today’s project world is increasingly defined by transparency, sustainability, flexibility, and collaboration all elements that decentralize control. Some industries and organizations have embraced this. Others see them as threatening and continue to implement tired practices incongruent with the working world today. I’ve seen young professionals attend training and return to their stations ready to use their newly learned skills, only to have managers tell them that’s not how things are done around here. I’ve seen studies report recurrent findings and recommendations, but core problems don’t seem to go away. What are we missing?

I suspect we’re in need of a seemingly subtle shift that will be challenging to implement. Parading around and touting management principles like those mentioned above means nothing if they aren’t practiced. More importantly, we cease to grow as an organization when we don’t keep up with changes in the way the broader world around us does business. Either we innovate or we become irrelevant.

As one NASA young professional recently said to me, “Good ideas don’t change the world—implementing them does.”