Dr. William H. Pickering (left), Director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, presents Mariner spacecraft photos to President Lyndon Baines Johnson in 1964. Photo Credit: NASA

July 31, 2012 Vol. 5, Issue 7

“Scientists may tell us where to go, but politics will tell us how fast we’re going to get there,” said Dr. Harry Lambright about the politics of Mars.

Dr. William H. Pickering (left), Director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, presents Mariner spacecraft photos to President Lyndon Baines Johnson in 1964.

Photo Credit: NASA

“The story of Mars is really the story of the interaction between science and politics,” said Harry Lambright, professor of public administration, international affairs, and political science at the Maxwell School at Syracuse University, during a lunchtime presentation hosted by the NASA History Office at NASA Headquarters on June 28, 2012. “And there are certain lessons you can draw [from it],” he said.

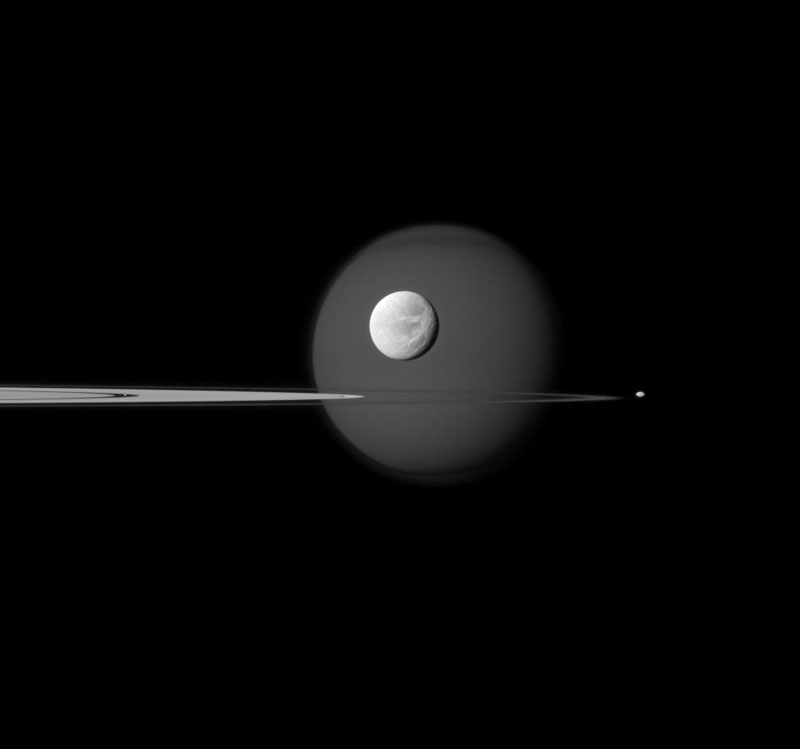

Since the Mariner Program returned the first images of the Martian surface in 1964, answering the question of whether there is—or was—life on Mars and sending humans to set foot on the Red Planet have been the dreams of many scientists and engineers. Politicians, who have a separate portfolio of competing interests, have not always shared this sentiment.

“Politics is what moves programs forward or holds them back,” said Lambright. “The real problem we have between science and government is the total disconnect in time frame.” Scientists have to think and strategize long-term to keep up with election cycles and constituent needs that politicians strive to meet.

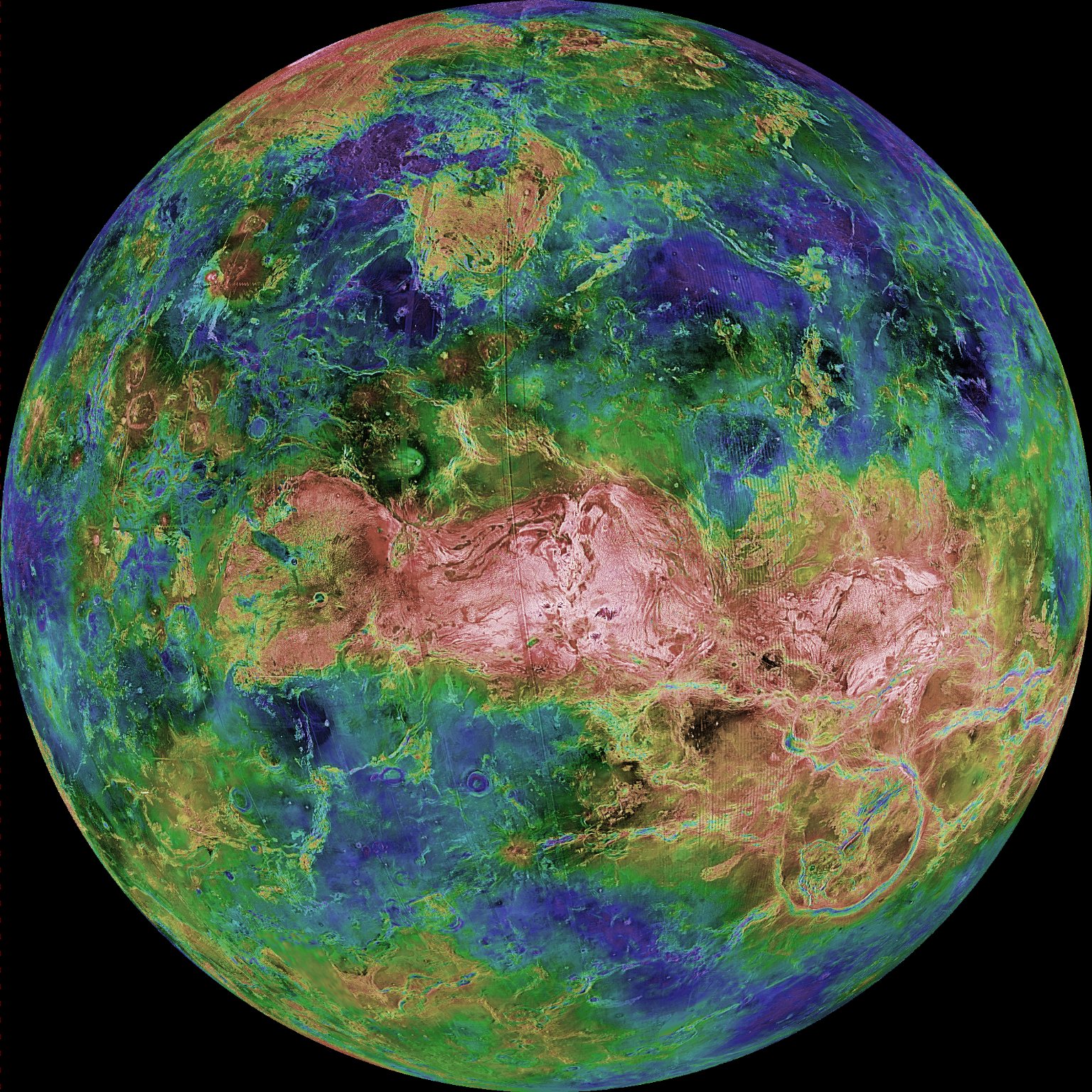

Lambright also discussed cost containment and competing programs as additional elements that have also had a hand in the story of Mars exploration. “Mars is not the only planet, and the Mars program is not the only program in the science division,” explained Lambright. Having stakeholder support is critical to the continuity of Mars exploration and that support is contingent on effectively communicating the reasons to keep going back.

Lambright closed with the following words:

Mars exploration is a leading example of long-term, multi-generational program that has made progress. It is a success, it is a great success viewed over the long haul…. there have been ebbs and flows in the program. Science provides the direction, politics the pace. NASA is a player in the politics of Mars, a continuous player, but its influence is varied. NASA’s influence depends on how well its leaders play the hand they have been dealt by internal and external forces. Without question, the key word in the history of Mars is life, ‘life on’ and ‘life to.’

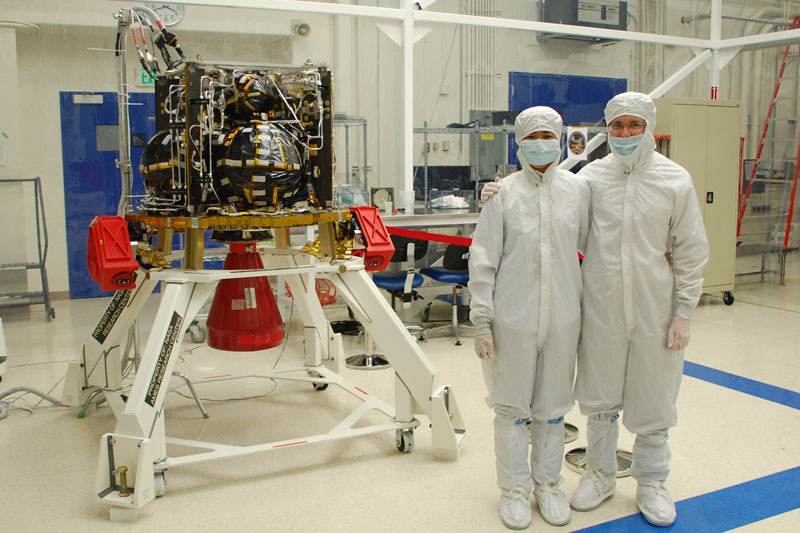

Sometimes NASA leaders have recognized that fact and sometimes they haven’t… if one were studying leadership, you’re talking about a relay race. Some leaders, some AAs, some As (administrators)… have carried the baton very well, others have dropped the baton or slowed down the race, but Mars is going to continue. And the reason Mars will continue no matter what happens with Mars Science Laboratory—in my judgment and I hope it is a great success—[is that] I think it has a broad constituency in the public beyond the scientific community. People do care about it.

Remember Ahab, Moby Dick, was asked, “Why are you on this quest?” He didn’t poke to his brain [and] do a cost-benefit analysis. He basically pounded his chest and said, “Because it fancies me here!” It fancies me here. Mars is in our blood. Mars is in our DNA. It is kind of the apotheosis of exploration for both robots and man and I think it will continue as long as we care about exploration.

Sign up for the NASA History Office quarterly newsletter to learn more about upcoming talks.