By Don Cohen

During her thirty-six-year career at NASA, Lynn Cline led U.S. delegations to the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space and served as NASA’s lead negotiator of the agreement that resulted in Russia becoming a partner in the International Space Station (ISS).  At the time of her retirement at the end of 2011, she was NASA’s deputy associate administrator for Human Exploration and Operations.

At the time of her retirement at the end of 2011, she was NASA’s deputy associate administrator for Human Exploration and Operations.

Cohen: How did you become lead negotiator for Russian participation in the ISS?

Cline: I was in the office of international relations, involved in early discussions of cooperation on human spaceflight, when the Soviet Union became Russia. Because I’d done that, my boss decided I should be the lead negotiator for the revision to the ISS agreement that was required to bring Russia in.

Cohen: What was especially challenging about the negotiations?

Cline: The multilateral dynamics. The original partners with whom we had legally binding international agreements did not want to become an afterthought or be viewed as less important just because they had a smaller budget or weren’t providing as large an infrastructure as the Russians. Group relations changed from when you were speaking bilaterally to when you were speaking multilaterally and depending on which combination of partners you had in the room.

Cohen: Was there an element of good-cop, bad-cop in the multilateral negotiations?

Cline: Absolutely. As lead negotiator I most often had to be the bad cop because the original partners—Canada, Europe, and Japan—were nervous that they would somehow lose rights and obligations by bringing in this larger partner. So when we were meeting without the Russians, either multilaterally or bilaterally, I would hear, “You can’t let the Russians do this, we insist on that, we can’t change this, we must have that.” When we got in the room with the Russians they would rely on me to do the talking. There were times when partners would play off of one another’s views. I could do it, too. I could tell the Russians, “Gee, I’d accommodate you but then I’d lose the Europeans.” Or, “The Japanese can’t change.” The other partners did the same thing. It was a challenge to understand what were the real issues and what were negotiating tactics.

Wherever we went, there was somebody who organized a dinner or something that we could do together. We got to know who was married, who had kids, where they went on vacation, what their hobbies were.

Cohen: What were some of the challenging issues?

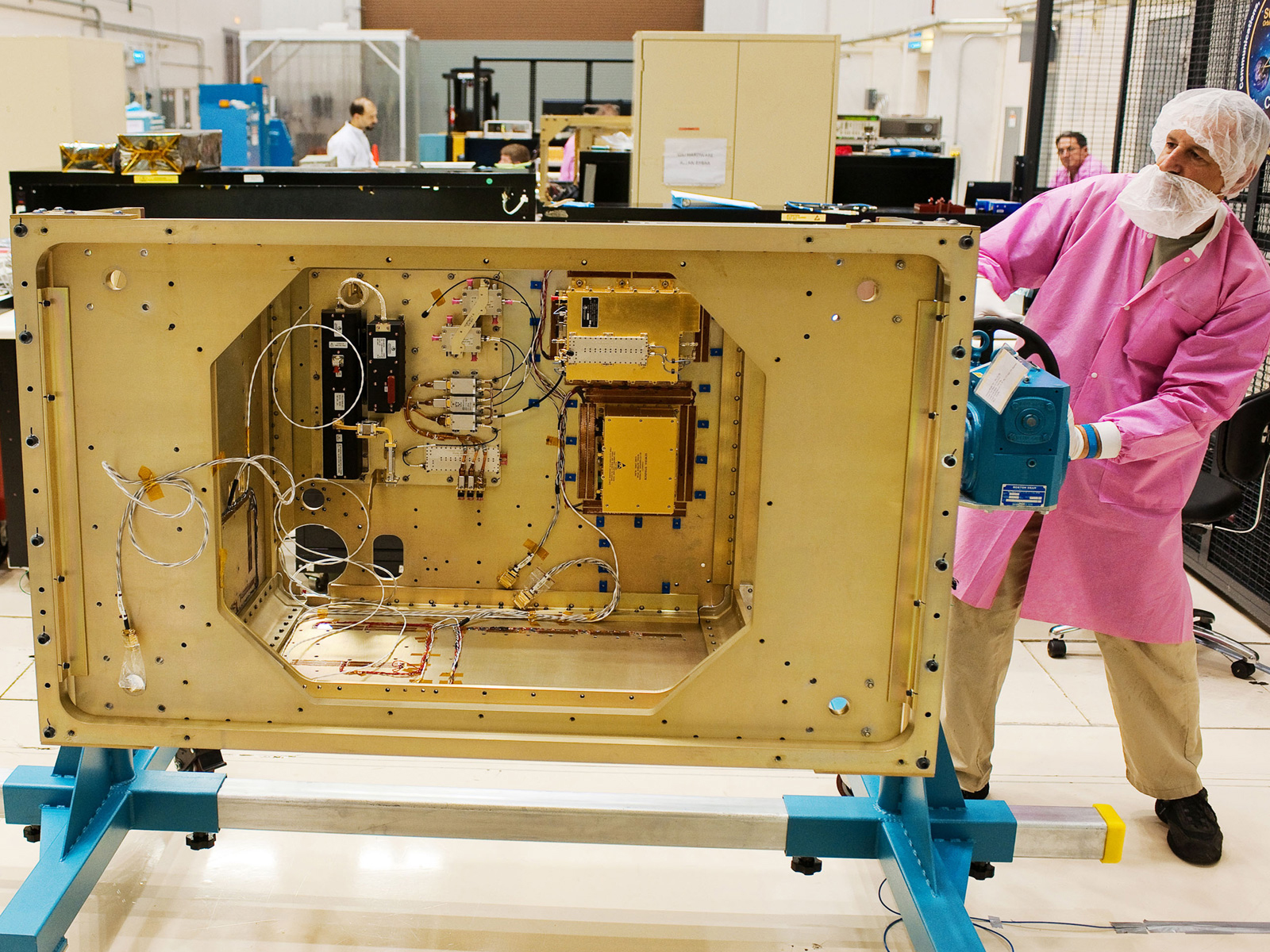

Cline: In the first round of negotiations, before Russia was brought in, there was a provision that said we’d endeavor to minimize the exchange of funds. If the U.S. was going to be the primary operator of the station and everyone was sharing the operational cost, then the partners would need to pay us their share. They did not want to send cash to the U.S. to meet those financial obligations; they wanted to provide goods and services instead. Out of that came things like the European Automated Transfer Vehicle. They wanted to spend their money on jobs with European industry and provide cargo services to pay part of their operating costs rather than send money to the U.S. Once we agreed to that understanding with Europe, Japan wanted to do the same. That’s how we ended up with the HTV [H-II Transfer Vehicle], the Japanese cargo vehicle. What we did in the discussions was ensure that the European and Japanese cargo vehicles were quite different to make them complementary. Similarly with the Russians, we did not want to be sending them money and they did not want to be sending us money. So we had to figure out how many things we could barter back and forth to help balance out those financial obligations. We ended up trying to trade off and come out even. We both have a mission control, one in Houston one in Moscow: let’s call that even. We both train astronauts: let’s call that even. We tried to balance everything out. In the end, there were some remaining financial obligations over and above the things that we traded off.

Cohen: For instance?

Cline: A lot of it ended up being U.S. payments to Russia for certain things. If we had nothing left to trade against, then we’d pay for it. The first element of the space station that was launched was built by the Russians but actually paid for by the U.S., and in the legal agreement is considered a U.S. element.

Cohen: There were so many moving parts in the negotiations; it’s amazing it all came together.

Cline: It was definitely a challenging and complicated process. Keep in mind that the negotiations took four years to accomplish. The invitation to the Russians to join the partnership officially was issued in 1993, and I guess it was ’97 when the negotiations were finally completed. Then the language of the negotiations had to be verified and so on. It was early ’98 when the signing ceremony was held.

Cohen: How much time did you spend actually meeting and negotiating?

Cline: I was on the road very frequently. There were multiple negotiations ongoing. At the top level, I was one of the NASA representatives to the intergovernmental agreement negotiations. That was a State Departmentled political multilateral agreement above the space agency level memoranda of understanding. We met periodically, one meeting in the U.S., one overseas, one in the U.S., one overseas. At the space agency level, they are all bilateral agreements. If Europe asked for changes, I would have to convey them in turn to Canada, Japan, and Russia and get all those countries to agree before I could agree to them. In the end, even though there are separate bilateral agreements, there are certain provisions that have to be identical across the board because you can’t have five different management approaches. Since we were meeting bilaterally, it was a highly iterative process. You had to come back to the same points over and over. How many rounds do you have to go before everyone is on board for the same compromise for that particular provision? It was very time consuming.

Cohen: Did you enjoy the process?

Cline: At times. At times I was ready to tear my hair out. One of the things we agreed to at the beginning of our negotiations—here is a lesson in human nature—was that it would be good for us to get to know each other as human beings outside the negotiating room. We agreed that whoever was hosting a round of negotiations would organize a social event. Everybody would pay their own way. Wherever we went, there was somebody who organized a dinner or something that we could do together. We got to know who was married, who had kids, where they went on vacation, what their hobbies were. It made it a pleasure to work with these people. You could disagree across the table—everyone respected that we were representing what our agencies needed—and then you could leave the disagreements on the table and go out and enjoy one another’s company. I made so many friends and learned so many things. I don’t regret doing it at all, as difficult as it was.

We started out fighting over principles that we thought were going to be really important, but once people start working together and build trust and respect for one another, they figure out how to work together without having to go back to chapter and verse of the agreement

Cohen: Were there wrong turns or dead ends in the negotiations?

Cline: The most difficult issue was the allocation for operations and utilization. In the first round of negotiations, before Russia joined the partnership, there was a calculation done of the approximate value of each partner’s on-orbit contribution. Everybody had a certain percentage allocation and that percentage number determined how much crew time you got, how often you were allowed to fly an astronaut from your agency. It determined your cost obligation as well. We tried to figure out how to bring Russia into the scheme and could not do it. No matter what I proposed to the Russians as the basis for valuing their contribution, they had a different view. We couldn’t figure out how to reallocate all the resources after adding in Russia. That was a major sticking point. We pushed to fully integrate Russia into the rest of the program and make it a single, unified, cohesive international space station. In the end, we backed off and ended up with what we refer to as the “keep what you bring” solution. The Russians get to keep all the allocation of operation and utilization resources and obligations for elements that they contributed. On all the rest of the station, we maintained the sharing on a percentage basis from the original negotiations, though the percentage shares evolved over time. That was one issue where we never could reach a common understanding, so we ended up with these two parallel approaches.

Cohen: Does that mean there are resources not shared with the Russians and vice versa?

Cline: Yes, but the allocation agreements allow for barters of various sorts. As the program evolves and things change, we have made trades across those borders. For example, the U.S. negotiated with Russia for the U.S. to provide power from the U.S. power system to operate the Russian segment elements, rather than them bringing up a whole separate power system. As difficult as they were to negotiate when everything was on paper and hypothetical, those allocations are only starting points.

Cohen: Am I right in thinking that you undertook this work without a technical background?

Cline: That is correct. My background was French language and culture. I came into the international office as a co-op student when I was in college. As lead negotiator, I was not expected to be the technical expert. I had a whole team: someone from the program office; someone representing the science community; someone from Houston who did a lot of the coordinating with the different elements at Johnson Space Centerthe crew office, the safety office, the engineering folks, etc. I had someone from the legal office for all the legal terms and conditions. We had pre-meetings and we had a postmortem after each negotiating session. I relied on the other members of the team to make sure we understood what concerns other organizations at NASA might have that we needed to represent. We had constant feedback on all those sorts of things.

Cohen: So lack of technical knowledge was not a problem?

Cline: Keep in mind that the agreements at this level are not highly technical. They’re more about the management structure, the rights and obligations. In parallel with what we were doing, there were ongoing technical discussions. We did have feedback going back and forth between those two levels. As an example, one of the things in the memoranda of understanding is a list of what each partner is providing. It was pretty well fixed for the U.S., Canada, Europe, and Japan because we had been at this for a while. I had a list of elements the got to the next round of negotiations, I’d be told the list wasn’t correct any more because they had discussions with JSC [Johnson Space Center] and decided to change a few things. The technical guys were off doing their technical thing. Sometimes I was ahead of them, and sometimes they were ahead of me. We just tried to keep in communication.

Cohen: In retrospect, would you say the ISS agreements have been an effective basis for operating the station?

Cline: The framework I inherited from earlier negotiations is flexible. One of the things you need to avoid as a negotiator is getting too precise because things change, especially on a long-term program. Technical issues will arise; the policies of governments will change; administrations will change. I think these agreements have been remarkably flexible. We started out fighting over principles that we thought were going to be really important, but once people start working together and build trust and respect for one another, they figure out how to work together without having to go back to chapter and verse of the agreement and insist on what it says in Article 4, Chapter 3. It just becomes people working together who have a common goal. There were huge concerns in negotiations about would the U.S. ever exercise its right to make a decision even if the partners objected. Those were very important principles during the negotiations and certain rights were part of the agreement. But the fact of the matter is everything one partner does affects the others. The incentives are there to compromise and make things work. Once you get the politicians and the negotiators out of the way and you let the program people run the project, there’s a lot of freedom to make the program work the way you need it to.

Cohen: The shared goal is so important.

Cline: We each came to it with a slightly different perspective and so the goal may not have been flavored identically for every country, but we all shared that vision. The program has evolved and survived some very difficult things. One was the fact that the Russian element—the first element—was delivered eighteen months late, I think it was. That pushed back the entire schedule. Then we had the Columbia accident. I think it’s amazing that the partnership was strong enough to keep going by relying on the Russians and reducing our crew size to limit the logistics requirements. We came through that and resumed assembly.

Cohen: Are there lessons from this negotiating experience that apply to other kinds of international issues?

Cline: There are common elements to international negotiations. Some are common sense things: understanding, for instance, what your partner’s objectives and needs are. You can’t just be a dictator and say, “This is how it’s going to be.” You have to have that give and take and listen and understand the other person’s perspective. A lot of it is basic good communication and building trust and relationships.

Cohen: Aside from good communication and building trust and understanding, are there other lessons you’d pass on to other negotiators?

The Space Station agreements didnt happen magically. There were years of pre-discussion that identified common interests.

Cline: Sometimes what you think is the issue may not be. There were a couple of articles in the agreement that the Russians knew were really important to the United States. They were provisions on which I had zero flexibility. The Russians refused to agree to any of those terms. Toward the end, my counterpart Alex Krasnov and I could have traded places and given one another’s speech on one article, we’d done it so many times. When we reached the last round of negotiations, I put on my flak jacket and was ready to go through it again, expecting no change. But the Russians had finally got everyone on board internally; they were ready to sign the agreements. I started on my normal talking points and my counterpart from Russia said, “OK, no problem.” I almost couldn’t talk for a minute. That happened three or four times. Things that were really tough sticking points for me, that I had no flexibility on, they took advantage of to keep the negotiations going until they got the other things that they needed and did whatever they needed to do domestically to get everyone on board. I thought they really cared about those points, that they really meant it when they were fighting me tooth and nail about all those clauses. They didn’t. What a negotiator is telling you across the table might be what they really need but it could also be a negotiating tactic.

Cohen: Before he agreed?

Cline: There were times I wasn’t sure we would ever get there because I couldn’t come up with any more arguments to use.

Cohen: So the lesson is, hang in there because circumstances may change.

Cline: Right. And suppose those were points I did have flexibility on. I might have compromised and agreed to things I didn’t need. If you have a principle that you feel strongly about, it’s worth sticking to.

Cohen: Are there opportunities for future international space negotiations coming up?

Cline: It’s not clear to me how soon. The most important thing is to keep the dialogue open so that when real opportunities do become available, you’ve already built the foundation. The space station agreements didn’t happen magically. There were years of pre-discussion that identified common interests. Groups like the International Space Exploration Coordinating Group, which has fourteen space agencies in it, talk regularly about what sorts of things they’re thinking about. No one has a specific plan; they’re not negotiating agreements. They’re carrying on the dialogue. When there is a desire to do the next human exploration spaceflight activity, they’re poised and ready and know what the various countries’ likely interests are and where they can contribute.

More Articles by Don Cohen

- The Sky Crane Solution (ASK 47)

- Scientific Visualization: Where Art Meets Science and Technology (ASK 47)

- Knowledge Topics: A Vital Project Resource (ASK 47)

- In This Issue (ASK 47)

- In This Issue (ASK 46)

- View More Articles

the power of habit