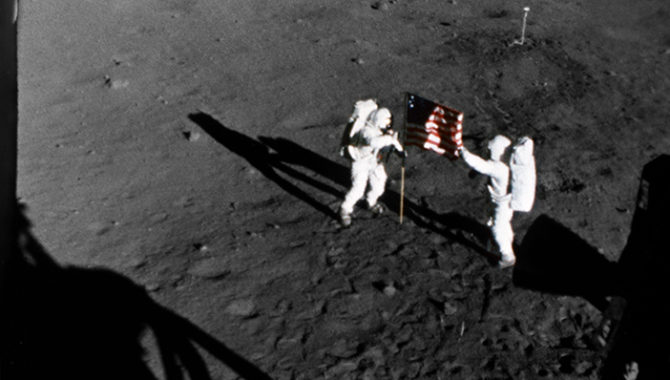

The deployment of the flag of the United States on the surface of the moon is captured on film during the first Apollo 11 lunar landing mission. Here, astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, commander, stands on the left at the flag's staff. Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin Jr., lunar module pilot, is also pictured. The picture was taken from film exposed by the 16mm Data Acquisition Camera (DAC) which was mounted in the Lunar Module (LM). While astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin descended in the Lunar Module (LM) "Eagle" to explore the Sea of Tranquility region of the moon, astronaut Michael Collins, command module pilot, remained with the Command and Service Modules (CSM) "Columbia" in lunar orbit.

Photo Credit: NASA

Forty-five years ago this month, we landed a man—actually two—on the moon, and the world raised the bar to success by a skyward leap.

Since that fateful day in 1969, we have all heard, at one time or another, the prologue “They can land a man on the moon, but they can’t…” to complain about some technologically disappointing “thing” or circumstance. The judged “they” are not inevitably NASA, of course, but are always an authoritarian “they” not living up to the complainer’s expectations.

Tired of hearing this “moon landing” prologue before a complaint, the comedian Jerry Seinfeld once joked, “Neil Armstrong should have said, ‘That’s one small step for a man and one giant leap for every complaining SOB on the face of the earth.’”

Requirements define the parameters of what successful processes and outcomes look like. Whether it is an auto part that breaks or dress hosiery that rips, we expect—even before the moon landing—that our paid-in-full experiences and items work without fail or tragedy, and that they rise to a level of success all the time.

We consistently desire the same of what we want ad infinitum, and moreover, even better. Faster, better, cheaper. We listen to the songster Paul Simon lament, “The thought that life could be better is woven indelibly into our hearts and our brains,” and admit that perhaps the hardest thing to manage is our own expectations.

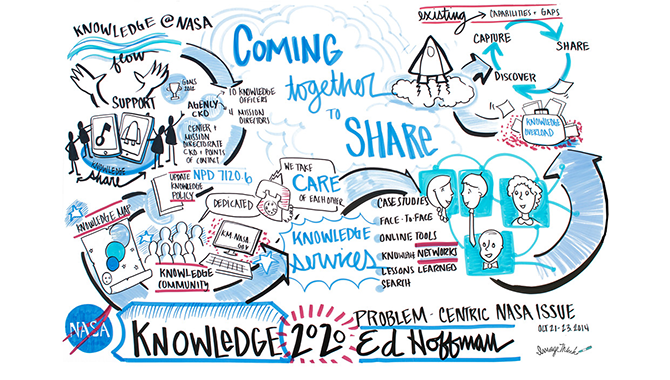

At first glance, knowledge management and services may seem to be codifying and disseminating doom and gloom. Practitioners engaging in knowledge are capturing and sharing lessons learned and gleaning from case studies what should never be repeated. However, knowledge advocates are also—and often—flexing the precious, metal-like chains of mentoring across generations and eagerly interlocking networks of experts with those looking for expertise. Ultimately, knowledge champions strive to hold up to the spotlight best practices as if they were diamonds formed by the greatest of earth-moving forces. Best practices are like diamonds, cutting through challenges like nothing else can.

Though it is possible to formalize best practices through a knowledge map, these practices do not become the best practices easily or through mere luck. If we investigate carefully, we can discern both the geology and geography of best practices. By following how knowledge flows and by charting how essential decisions are made—through inquiry, analysis, testing, assessment, and reflection, we can see the evolution of how data becomes information, how information becomes knowledge, and how knowledge becomes critical knowledge.

We have an obligation—born of all our past exemplars—to build our future by and for sharing the wealth of knowledge.