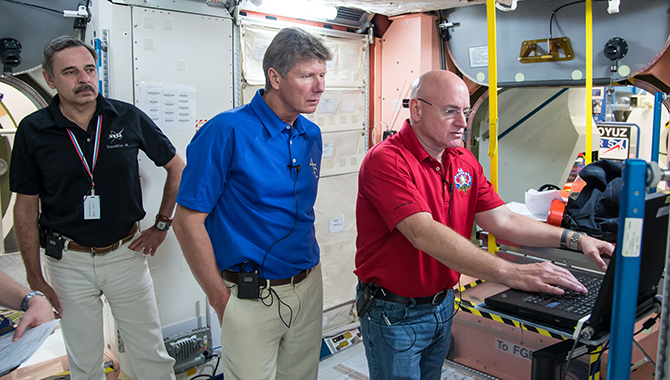

Mikhail Kornienko (left) and Scott Kelly (right) with Russian cosmonaut Gennady Padalka. Padalka will join Kelly and Kornienko for the first six months of their mission.

Photo Credit: NASA/James Blair

NASA’s commitment to manned deep space exploration continues with an extended mission to learn more about the long-term effects of microgravity on the human body.

In December 2014, NASA and the world witnessed the successful initial flight of Orion, the first spacecraft in four decades designed to carry humans beyond low Earth orbit (LEO). In March 2015, the agency and its international partners will take new strides along the path toward Mars: for the first time ever, two astronauts will spend an entire year on the International Space Station (ISS) to uncover more information about how the human body responds to long-duration exposure to microgravity environments.

Along with their international ISS partners, NASA and the Russian Federal Space Agency Roscosmos selected two individuals for the yearlong mission: astronaut Scott Kelly and cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko. Both are spaceflight veterans who have spent time on the ISS before, yet they are particularly excited about this mission. “We built this space station as an international partnership, connecting these modules in low Earth orbit,” said Kelly. “[We traveled] around the Earth at 17,000 miles per hour in a vacuum, extremes of temperature and pressure, building this facility that allows us to understand how to operate for long periods of time in space to allow us to someday go to Mars.”

Kelly and Kornienko will remain on the ISS from March 2015 to March 2016, twice the duration of a typical NASA mission. During that time, scientists will monitor the changes their bodies undergo to better understand the long-term human physiological response to spaceflight. This expanded understanding is essential for planning future manned missions beyond LEO. Currently, NASA has robust data concerning the effects of six-month missions in microgravity environments. But the agency and its international partners need to know much more before they can embark on missions into deep space. “The research that we’re doing on ISS,” said Julie Robinson, ISS Chief Scientist, “helps us make sure that crews will be healthy and ready to go to Mars when we have the systems ready to support that.”

More than 400 scientific experiments will be conducted over the yearlong mission. The investigations will span several distinct categories of research, including the psychological effects of long-duration spaceflight, ocular health and the body’s response to the fluid shifts that are known to occur in microgravity, and the effects of prolonged weightlessness on bone, muscle, and the cardiovascular system.

At the end of the year, the research will continue on Earth: scientists will work with Kelly and Kornienko to examine the severity and duration of changes in their ability to perform functional tasks after a year in microgravity. Typically, remaining in space for six months or longer results in physiological changes that impact astronauts’ abilities to perform basic tasks. A better understanding of this impact and how it might be addressed will be critical for Mars missions, in which crews are expected to travel in a weightless environment for seven or eight months before reaching the red planet, and then to perform tasks such as constructing a Mars-based habitat with little time for recovery.

Kelly’s mission will have a unique twist: his twin brother Mark, a former NASA astronaut, will participate in the mission from Earth, where he will undergo tests to serve as a ground-based control. “A group of ten premier scientists are looking at the genetic basis of disease and the genetic basis of many of the different processes that affect astronauts,” said Robinson. “[They] have partnered in this twin study to make it a state of the art investigation of the interaction between genes and the space environment in affecting the health of astronauts.”

The mission does not represent the first time that humans have spent 12 months in space. During the 1980s and 1990s, four Russian cosmonauts spent a year or longer on the Mir station. But there is an important distinction between those experiences and the current mission, explained Robinson: “There have been major changes in our understanding of human physiology and of human physiology in space. All of the things we’ve learned from the space station weren’t known at that time. And we’ve got a genetic understanding of disease that is completely new from when the last cosmonauts flew for long periods of time in the 1990s.” As a result, the information provided by the upcoming yearlong mission is expected to significantly advance scientific knowledge to help expand the frontier of human spaceflight.

Learn more about the research goals of the one-year ISS mission.