While on the International Space Station (ISS) for the One-Year Mission, NASA astronaut Scott Kelly also participated in the Twins Study, which compared his molecular information to that of his twin brother, Mark Kelly, a retired NASA astronaut who stayed back on Earth. Here, Kelly gives himself a flu shot as part of an investigation into the twins’ immune responses.

Credit: NASA

As NASA moves forward on the journey to Mars, researchers share new information about the effects of prolonged spaceflight on the human body.

Astronauts experience unique physiological and psychological stresses in space. To support planning for manned missions to deep space, NASA’s Human Research Program (HRP) conducts a wide range of investigations designed to assess and address risks to crew.

One example is the One-Year Mission, which came to a close nearly 12 months ago when NASA astronaut Scott Kelly and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko returned to Earth after 340 days on the International Space Station (ISS). The mission was designed to advance understanding of the human body’s response to long-duration spaceflight and the challenges that prolonged weightlessness could pose to astronauts who will someday travel beyond low Earth orbit (LEO). Mission experiments spanned seven categories: functional investigations, behavioral health experiments, exploration of visual impairment, metabolic and microbial investigations, physical performance studies, and examination of human factors, such as how astronauts interact with their environment in space.

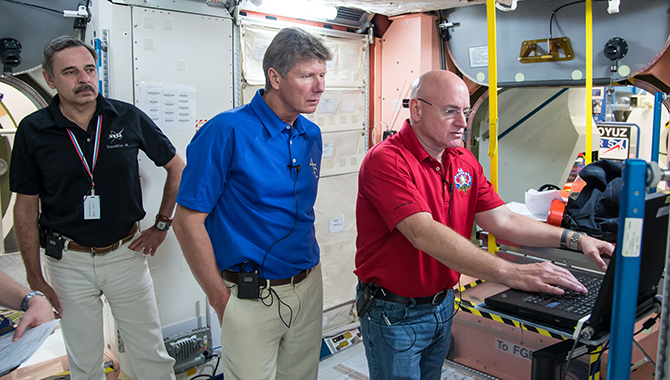

While participating in the One-Year Mission, astronaut Kelly was also involved in a second investigation: the Twins Study. This project collected and compared molecular information from Scott Kelly, while on the ISS, and his twin brother Mark Kelly, a retired NASA astronaut who remained on Earth. By examining the similarities and differences in data from two individuals with identical DNA—one in space, one on the ground—researchers hoped to gain greater insight into the effects of prolonged microgravity exposure on human physiology and pinpoint areas for future investigation involving additional astronauts on station.

Preliminary findings from both investigations were presented at NASA’s HRP Annual Investigators’ Workshop in Galveston, Texas, at the end of January. For the One-Year Mission, several tests revealed a difference between the performance of Kelly and Kornienko compared with astronauts on station for shorter durations: six months or less. One example was the Functional Task Test, which was designed to inform understanding of crew members’ abilities to perform tasks upon landing on Mars. Conducted as soon as the crew returned to Earth, the tests indicated that they had the greatest challenge with tasks involving postural control, stability, and muscle dexterity. A second area of difficulty emerged in the Fine Motor Skills tests, which examined their ability to accurately operate computer devices after landing, an activity that would likely be necessary for crew arriving at Mars. During the test, which involved four tasks conducted on an Apple iPad, both crew members exhibited reduced accuracy and reaction time. Another area of difference between the One-Year Mission crew and astronauts on the ISS for shorter durations was observed in the Sleep Wake Cycles study. Kelly and Kornienko averaged an additional hour of sleep compared with astronauts who were on station from 2004-2011. (Researchers cautioned that this could be due to a variety of factors, including better scheduling, fewer work shift changes, and a lighter workload since construction of the ISS was completed.) Finally, investigations into neurocognition functionality and neuromapping revealed similar behavioral changes between crew on the ISS for 12 months versus six, although longer-duration spaceflight was associated with greater brain region involvement when processing inner ear inputs.

There were differences in test results between Kelly and Kornienko as well, even though they were on station for the same amount of time and followed the same diet and exercise regimen. The Field Test Investigation revealed markedly different postflight recovery experiences, suggesting that preflight training may correlate highly with performance after landing. The Visual Impairment and Intracranial Pressure (VIIP) study found that one of the men exhibited VIIP (optic disc edema, choroidal folds, refractive error changes) while the other did not. The reasons for this are unknown, but researchers speculated that it could be related to observed differences in cardiovascular parameters between the two crew members.

Preliminary findings from the Twins Study were also shared at the Annual Investigators’ Workshop. Working with biological samples obtained from both men before, during, and after Scott’s year on the ISS, researchers noted several areas of difference between the twins. Scott experienced some alteration in lipid levels during the course of the mission that indicated inflammation. He also had a decline in bone formation during the second half of the mission that was not mirrored by his brother on the ground. In addition, an epigenomics study uncovered chemical modifications to Scott’s DNA not exhibited by Mark. These changes, however, were reversed upon returning to Earth.

Scott also experienced positive shifts while in space compared with Mark. Protective regions, called telomeres, on chromosomes in his white blood cells actually lengthened while on station, a notable development because telomeres typically shorten with age. However, they began to decrease again after returning to Earth. His IGF-1 hormone levels increased while in microgravity, indicating positive bone and muscle health despite the observed decline in bone formation.

Studies involving immune function revealed little variation between the men, while genome sequencing studies have produced few findings so far. The greatest divergence between the twins’ data was seen in their microbiomes: the individual collection of microbes that reside in the body. Researchers attributed the differences to their dissimilar diets and environments during the mission.

Results from both the One-Year Mission and the Twins Study will be used to inform understanding of the risks to crew during future missions to Mars. Investigators have made clear that while the new data offers unique insight into the effects of prolonged spaceflight on human physiology, studies involving additional subjects are needed before broad conclusions can be made. For now, findings from the two studies will be compared with the 15 years’ worth of data from astronauts who lived on the ISS for six months or less. More results from both studies will be shared later this year.

As one of only two people to spend nearly a year on the ISS, Scott Kelly has a unique perspective on whether humans are equipped to spend long periods in microgravity environments. Based on his experience in the One-Year Mission, he said, “I personally think going to Mars, if it takes two years or two and a half years, that’s doable.”

Read an APPEL News article about the One-Year Mission and Twins Study.

View a Science@NASA video about the Twins Study.

Watch an HRP video about the important role of microbiomes in human health on Earth and in space.