NASA astronaut Scott Kelly participated in an extra-vehicular activity (EVA) on November 6, 2015, as part of the One Year Mission on the International Space Station. The EVA lasted nearly eight hours.

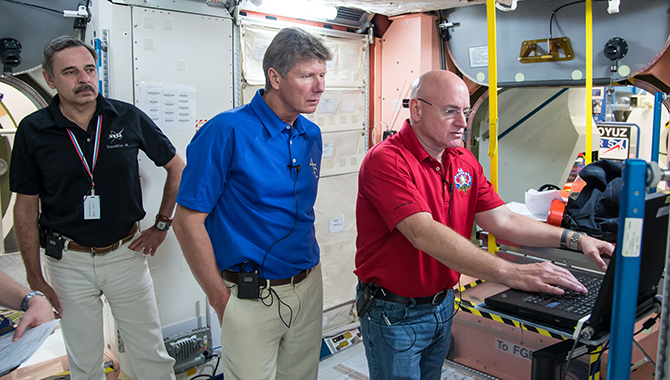

Photo Credit: NASA

After spending a year on the International Space Station (ISS), NASA astronaut Scott Kelly believes a long-duration crewed mission to the red planet is possible.

“I personally think going to Mars, if it takes two years or two and half years, that’s doable,” said Kelly.

As one of only two people ever to spend 12 months on the ISS, Kelly has a unique perspective on whether humans are equipped to spend long periods in confined, microgravity environments, such as the kind that would be required for a manned deep space mission to Mars. He and Russian Federal Space Agency (Roscosmos) cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko recently returned from the One Year Mission, an ISS-based international initiative to advance understanding of the human body’s response to long-duration spaceflight.

This wasn’t Kelly’s first ISS mission, and he has noticed differences in the way his body is responding to being back on Earth after such an extended time in zero-G. “I flew 159 days last time, and when I got back, I felt like I was feeling pretty good….Initially, this time, coming out of the capsule, I felt better than I did last time. But at some point those two lines have crossed, and my level of muscle soreness and fatigue is a lot higher than it was last time,” he said. “I also have an issue with my skin that, because it hadn’t touched anything for so long, like any significant contact, it’s very, very sensitive. It’s almost like a burning feeling wherever I sit or lie or walk.”

Despite these unexpected sensations, Kelly believes NASA is on track for sending humans to Mars in the not-too-distant future. “I think there’s still things we have to learn, but I think we can learn them. There are challenges we still have to meet—like the radiation issue. If you take six months to get there, that’s a lot of radiation the crew is getting. If you get there quicker, then it’s less radiation. So maybe the solution is a balance between how you protect the crew versus maybe you have a propulsion system that gets you there faster.” He added, “But I think we know enough and I think we’re close enough that if we made the choice, ‘Hey we’re going to do this, we’re going to set a goal, we’re going to set a time,’ yeah—I think we can do it.”

Over the course of their 340 days on the space station, Kelly and Kornienko participated in hundreds of experiments, including 18 Human Research Program studies designed to examine the effects of prolonged spaceflight on human psychology and physiology. Studies for the One Year Mission spanned seven categories, including functional investigations, behavioral health experiments, exploration of visual impairment, metabolic and microbial investigations, physical performance studies, and examination of human factors, such as how astronauts interact with their environment in space.

While the on-orbit segment of the mission is complete, most of the data from the mission has yet to be analyzed. Some of the samples are still on the ISS and won’t return to Earth until May, when SpaceX will provide transportation for frozen materials.

“Now we’re in the phase of collecting the data and starting to analyze the data and seeing what we really learned from this mission,” said Dr. John Charles, chief scientist for NASA’s Human Research Program. “[E]specially for the Twins Study, the metabolic data that are required are going to be batch analyzed, which means all the samples—or most of the samples—will be analyzed by the same technician, in the same hardware, at the same time, in the same place, so any differences we see are not related to variations between the technicians or the location or the time or how long they were in the freezer and so forth.”

The Twins Study focuses specifically on Kelly and his identical twin brother, retired astronaut Mark Kelly, who spent the yearlong mission on Earth undergoing the same studies as his brother in order to provide a baseline for comparison. Looking at the areas where Scott’s results vary from Mark’s, said Charles, “will tell us what areas to investigate in the future on astronauts. Not on twins, because there [are] no more twins in the pipeline, but on astronauts in general using this new set of what I call 21st century medical techniques and technologies to supplement the ongoing research we’re already doing.”

It was the Kelly brothers’ idea to include Mark as an element in the One Year Mission. “It can’t be [over]stated,” said Julie Robinson, chief program scientist for the ISS, “what Scott and Mark gave to science by coming to NASA and saying: ‘Why don’t you take advantage of the fact that we’re twins?’” For both men, the study will continue for close to another year. It will be longer still before information on the results of their study is widely available.

“We have plans for data collection on both Scott and Mark up to nine months after this landing. And that’s just data collection. Not even including the analysis time,” said Charles. “And then NASA likes to give the investigators a good solid year to analyze their data and then to write it up for publication so it can go into the publication, into the scientific literature, and be peer-reviewed.” He added, “So this time next year I’m hopeful we’ll start seeing the initial results come out from the investigations that were fairly quickly completed and fairly quickly analyzed. And then I look for a constant stream of insights and results from this mission for at least another year after that.”

After spending the past year on orbit, Kelly now holds the record for the number of days spent in space—520—for any U.S. astronaut. Kornienko is close behind, with 516 days in total. Despite spending so much time in close quarters, the two did not tire of working together. “[H]e‘s a great, great guy and it was a privilege flying with him and he’ll be a life-long friend of mine,” said Kelly.

The data from their experience on the station is expected to significantly advance insight into human spaceflight. Nonetheless, more data will be needed before NASA and its partners send crew farther into space.

“We really would like to see 10 or 12 crew members with long-duration data in order to be confident that some [day]—when we go around the table, and Health and Medical says they’re “go” for Mars—that we know what all the risks are and we’ve alleviated them all,” said Robinson. Once the data from the One Year Mission is analyzed, NASA will determine whether to send up more crew immediately for long-duration flights on the ISS or if there are advantages to waiting before doing so. Either way, research on the ISS will remain a critical resource for studies concerning manned deep space missions at least until 2024.

“I was thinking about this when I was backing away in the Soyuz: what an incredible achievement that this space station is and this program is,” said Kelly. “I kind of knew that, going into it, but experiencing it every day for 340 days really hit home for me. How if we put our mind to it, we can achieve things that would seem impossible. Like if you would have said to somebody 30 years [ago], ‘Hey, here’s a picture of the space station we’re going to build and keep it manned for 15 years and do all this science and other operations on,’ people would have been like, ‘Are you crazy?’ …It’s just an incredible achievement that I think everyone involved in it, including the people that pay for it—the taxpayers—should be very proud.”

Watch a video about the One Year Mission.

Read an APPEL News article about the studies involved in the One Year Mission.

Learn more about the Twins Study.