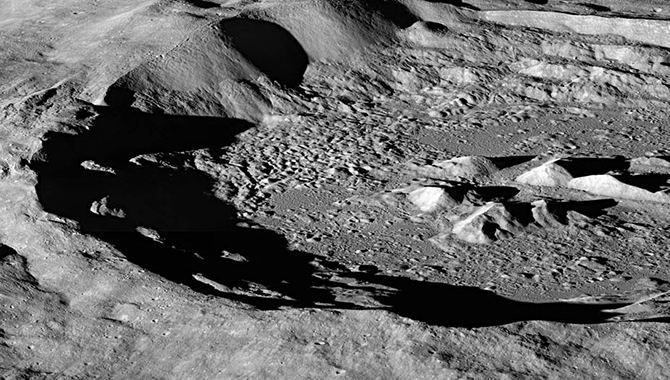

Lunar water could be used for drinking or its components – hydrogen and oxygen – could be used to manufacture important products on the surface that future visitors to the moon will need, like rocket fuel and breathable air.

Photo Credit: NASA

Twenty years ago, Doring Kindersley Publishing–the UK book company famous for the large “DK” logo on its lower spine and its floating art design–announced a new series of reference guides called DK Pockets.

The series had the tagline, “Pockets full of knowledge,” and each book was to be mass-produced in the shape best described as a small jewelry box. One of the first books off the press, not surprisingly, was an encyclopedia.

The 1997 edition of the Pockets Encyclopedia begins with an entry on The Universe and not the burrowing, nocturnal African mammal lucky enough to be called an aardvark. By page 30 of the thick book, the reader has zoomed into The Universe and now focuses on the Earth’s moon, which is reported to be “dead, waterless, and airless.”

To the best of the world’s knowledge in the 1990s, the moon appeared to be waterless. Since the success of LCROSS, we now know for sure that the moon has water in the form of ice. We could say DK had made a mistake by presuming the moon was without water, but let’s just call it a false assumption. It would have been okay to declare in 1997, in even a small encyclopedia, “There might be ice on the moon.” In a longer encyclopedia, DK could have added, “One day we will know for sure if there is water on the moon because of future scientific work.”

Without making decisions on what we think is true or most likely true, we cannot make a mistake nor can we achieve success. The website of the Office of the Chief Knowledge Officer (CKO), km.nasa.gov, has now launched a “My Best Mistake” series of stories that features enlightening mistakes that have taught the mistake-makers something and, through sharing as a lesson learned, the mistake can continue to teach without actually being made again, hopefully. Dan Andrews shares one of his best mistakes while he was working on LCROSS, a mistake unrelated the mission’s confirming the presence of ice. Andrews’s mistake has more to do with what happens when we think that something is too good to be true.

In Bias, Blindness, and How We Truly Think, author and psychologist Daniel Kahnemen writes: “Most of us view the world as more benign than it really is, our own attributes as more favorable than they truly are, and the goals we adopt as more achievable than they are likely to be… Because optimistic bias is both a blessing and a risk, you should be both happy and wary if you are temperamentally optimistic.”

If there are many lessons to be learned from assuming the moon had no water before LCROSS showed differently, let one of these lessons be of humility. All lessons learned have a component of that. What is critical is knowledge that we all need to know, and that buttresses our humility with a sense of ability. By surrounding ourselves with what has been tried as critical knowledge, wary of assumptions but acting on them anyway as best we can, we can sally forth.

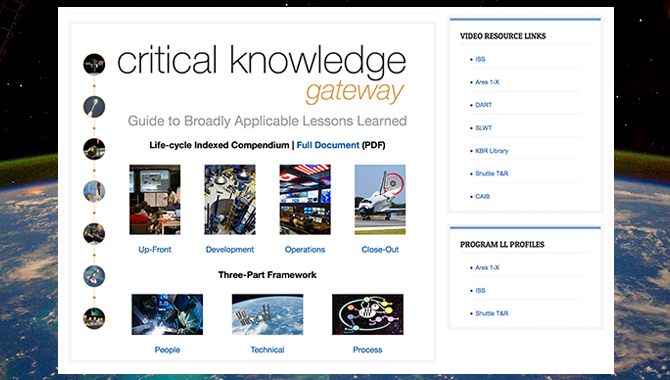

The Office of the Chief Knowledge Officer has also launched this month a Critical Knowledge (CK) Gateway on the km.nasa.gov website. The CK Gateway connects the NASA community to an array of NASA video-based lessons learned resources to assist users in formulating questions that need to be considered at various phases in a project life-cycle. The resources include lessons learned from the Space Shuttle Program, International Space Station Program, Constellation Program, ARES I-X Test Flight, DART Mission, and development of the Space Shuttle Super Lightweight Tank. The videos are indexed using a framework of the four-phase project lifecycle (Early-on, Development, Operations, Close-out) with People, Process, and Technical sub-elements for each phase. As it is updated, the CK Gateway will continue to integrate lessons in a dramatic and easily accessible manner.

It is only through always sharing our mistakes—often born from false assumptions—that we as an organization and as human beings can progress. Earlier this month, Charlie Bolden stated in his address to NASA and the world, “We all share a willingness to learn from our mistakes so that we can transform the impossible into the possible. That’s what we do.” Let’s continue to do so.