The XB-70 Air Vehicle 1 using drag chutes to slow down after landing.

Photo Credit: NASA/Air Force

On April 25, 1967, the XB-70—a high-altitude supersonic long-range bomber—flew under the NASA banner for the first time.

If the XB-70 program had gone as planned, NASA might never have gotten involved. The aircraft, known as “The Valkyrie,” was originally intended to replace the B-52. Designed to attain an altitude of 70,000 feet, travel at supersonic speeds, and carry a large payload, the XB-70 should have been the ultimate bomber. But the political world changed dramatically before the program could get off the ground.

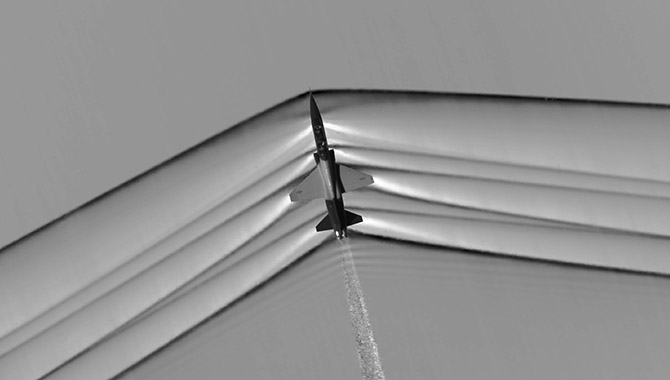

At the time it was approved for development, the U.S. Air Force needed an aircraft capable of delivering a nuclear strike at an altitude and speed beyond the reach of most anti-aircraft artillery. The XB-70 was designed to do exactly that. Engineers leveraged the concept of compression lift to boost the plane’s power. To take advantage of the shock wave created at supersonic speeds, the aircraft’s six jet engines were mounted in a tapered shape beneath the aircraft. This configuration forced air outward toward the wings, where hinges allowed the pilot to fold down the outer tips during supersonic flight, trapping air and increasing lift. The action also reduced drag and enhanced stability.

But while the plane was still in development, two changes in the military landscape altered the future of the XB-70. First, the accuracy of surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) improved dramatically, significantly increasing aircraft vulnerability. Second, intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) provided long-range strike capabilities at reduced cost and vulnerability to SAMs. As a result, in the early 1960s the XB-70 program was cut back to two experimental planes intended to provide data on supersonic transport (SST).

SST research was an area of enormous interest at the time. As Europeans worked on the Concorde, the U.S. became increasingly intrigued by the potential for commercial SST in America. By 1960, the Flight Research Center in Edwards, CA (now Dryden Flight Research Center) hosted several ongoing SST studies that examined landing, handling, and air traffic control issues associated with commercial vehicles traveling at speeds above Mach 1. The XB-70 would be a perfect fit for these studies.

Initially, only one plane was available: XB-70 Air Vehicle 1 (AV/1). During its first flight, on September 21, 1964, it failed to achieve Mach 1 due to a problem with the landing gear. But a month later AV/1 set a world record for sustained supersonic flight and reached Mach 3 a year after that. The plane was damaged while flying at three times the speed of sound, however, leading the program to conclude that it could only be used for research below Mach 2.5.

Fortunately a second XB-70, built to slightly different specifications, was under construction. Based on wind tunnel research, engineers added an extra five degrees of dihedral to each wing: an upward angle designed to enhance the aircraft’s stability at higher speeds. The plane also featured improved hydraulics, better skin construction, an automatic Air Induction Control System (AICS), and superior aerodynamics.

XB-70 Air Vehicle 2 (AV/2) performed exactly as hoped. It offered improved performance over AV/1, including the ability to fly above Mach 3 without incurring damage. Between January 1966 and June of the same year, the aircraft flew nine Mach 3 flights, providing high-quality data about issues impacting supersonic flight.

Encouraged by the performance of the improved XB-70 craft, NASA and the Air Force signed an agreement to use AV/2 to examine such issues as supersonic flight profiles and sonic boom concerns. These Phase II flights were scheduled to begin with AV/2 in mid-June 1966. But they never occurred.

On June 8, 1966, XB-70 AV/2 collided in mid-air with a chase plane piloted by Joseph Walker, who had been tapped as the project pilot for the upcoming Phase II studies. Both the chase plane and the XB-70 AV/2 crashed. Walker and AV/2 co-pilot Major Carl Cross were killed. AV/2 pilot Al White survived but sustained serious injuries and never flew the XB-70 again.

A modified XB-70 AV/1 was resurrected for the Phase II studies despite its lack of stability at speeds above Mach 2.5. NASA and the Air Force collaborated on 11 flights between November 1966 and January 1967 as part of the National Sonic Boom Program, which investigated the impact of supersonic flight in terms of noise pollution and compression damage to ground structures.

At the conclusion of Phase II, NASA took over the XB-70 program. The first NASA flight took place on April 25, 1967, with Air Force Colonel Joseph Cotton at the controls and NASA’s Fitzhugh Fulton as co-pilot. XB-70 AV/1 flew 12 times over the following year at different speeds, altitudes, and payload weights. Although the plane never traveled above Mach 2.57, it provided critical data that informed decisions about U.S.-based supersonic commercial transport. Due in part to findings from the XB-70 program, the nation decided against development of an “American Concorde.” Supersonic flight presented too many risks to make it commercially viable, including cost, potential noise pollution and damage associated with the sonic boom, and growing concerns about the impact of air travel in the upper atmosphere, where it might adversely affect the ozone layer.

The XB-70 AV/1 flew for the last time on February 4, 1969, from Edwards Air Force Base to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. It was then put on permanent display at the Air Force Museum, where it remains today. The U.S. SST program was cancelled two years later.

Learn more about the XB-70 Valkyrie.

View an image of the XB-70 in flight.