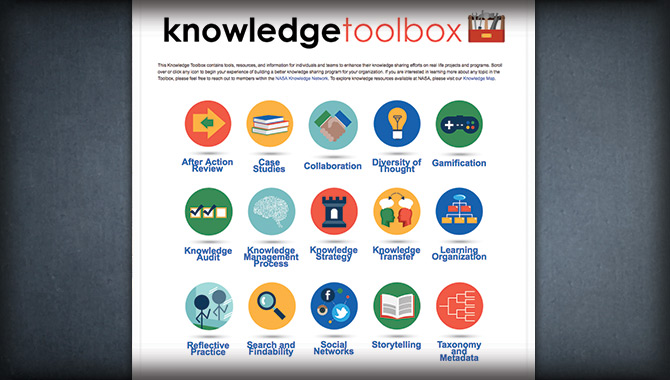

The Knowledge Toolbox contains tools, resources, and information for individuals and teams to enhance their knowledge-sharing efforts on real-life projects and programs. Analogous to how imperatives enhance and reinforce other imperatives, the tools, both conceptual and practical, found in the toolbox work together to create a stronger knowledge-sharing strategy.

Image Credit: NASA

To ensure mission success, NASA remains a project organization and program environment at its dual core.

Twelve strategic imperatives enable and direct the design, execution, and evaluation of Knowledge Services (KS) for the agency, supporting its projects and programs.

Project Management (PM): It beings with PM. All organizations, particularly NASA, require a methodology, which allows for rigor and agility in managing both temporary and ongoing processes and operations towards the achievement of defined requirements, project objectives, and anticipated outcomes. All of these must be aligned to strategy, especially in an era of constrained resources. In this context, PM is uniquely positioned as an adaptable discipline that fits the mission and can maximize the speed and application of learning.

Accelerated Learning: This is a set of tactics employing state-of-the-art online and other digital technologies, as well as more modern knowledge-sharing activities, traditional learning strategies, social media processes and tools, and cross-discipline knowledge into the broadest view of learning for an organization. Fast and relevant knowledge transfer and retention serves to clarify and prioritize organizational and developmental expectations for optimizing findability, accessibility, and searchability of knowledge resources.

Digital Technology: Online and electronic codification makes it possible to examine new frontiers of potential knowledge and access multiple sources of data and information; nonetheless, it simultaneously causes organizations to be increasingly buried in data and struggle to make time for focusing and reflecting. Technology is essential and necessary, but it is not a panacea for KS. Results can propagate from the application of technology, such as open, social network-centric, non-proprietary, adaptable frameworks. Digital tools accelerate learning processes to deliver “the right knowledge, at the right time” for particular needs while respecting context. The proper application of digital technology assists in achieving learning objectives and in making better decisions at a lower cost.

Lost-cost Innovation: A frugal mindset views constraints in an era of restricted and diminished resources as opportunities, leveraging a strategy of sustainability and a focus on organizational core competencies that will function to decrease complexity and increase the probability of better outcomes. Sustainability has gained momentum as the availability of resources increasingly impacts business decisions. Organizational requirements for a new product or service involve what must be achieved rather than what it can be done with unlimited scope, ensuring organizational capacity in areas such as technological, social, political, economic, and learning dimensions are part of the frugal innovation process. In a mutually reinforcing perspective, other imperatives, such as Transparency, which allows the team to share knowledge and experience to improve and innovate, support all efforts where “less is more” and streamlining is key.

Transparency: Open operations are an important consideration for the portfolio of organizational projects and programs to seem genuine. Numerous team members, customers, stakeholders, strategic partners, suppliers, and others interested and invested in organizational strategies and project processes create a network of trust often advanced through communication and digital tools. Transparency, which is built into the strategic business process, encourages benchmarking, sharing, collaboration, leveraging, and innovation, translating economies of scale and a breadth of lessons learned. Even in a structured environment, nothing is hidden for long: errors travel at the speed of light. Communications should be carefully defined across boundaries, as intensity and frequency of messaging is managed; for example, “NASA Only” stakeholder communities may expect to be informed about progress at a higher level, but not as frequently or in-depth as external audiences.

Leadership: Without effective, supportive leadership, KS fails. True leadership occurs with the insight that things should change, but also the realization that the reasons for change may be clear to leaders themselves but not necessarily clear to others. Effective leaders align projects with organizational strategies, missions and goals; this is admittedly easier said than done in the modern environment of information overload and rapid change. Successful implementation happens with a carefully communicated vision, leadership focusing on that vision, and attention to detail on implementation. There exists an external stakeholder community, as well as an internal project team, whose development, skills, and talents need to be understood and managed by leaders.

Talent Management: For NASA, talent management is organizing the variables in abilities, assignments, attitudes, and alliances (4 A’s). Each addresses the specification, identification, nurturing, transfer, maintenance, and expansion of the competitive advantage of practitioner expertise and competence. Diversity goes beyond the classic categories of color, race, religion, and national origin to domestic and international variables important to geographically dispersed and cross-disciplined teams, as well as divisions in work sectors, such as government and industry. Diversity allows groups to leverage experience, knowledge, focus, passion, and to bring talents and interests to the table. These characteristics strengthen both inductive and deductive problem-solving approaches, affording innovation, and developing individuals and teams, informally and formally.

Certification: Objectives and curriculum development of learning standards establish both validations and functions in benchmark achievement in defined categories of practitioner performance and capability. Formalized learning also provides organizations and practitioners the means to create trust with senior leadership, colleagues, team members, customers, and stakeholders and to provide a lexicon, pedagogy, and framework for change, as well as methods to address emerging or evolving performance requirements. For KS and PM practitioners, certification provides a clear roadmap for individual and team development, reflected in diverse and reinforcing projects and programs.

Portfolio Management: Process integration of projects with strategy creates an organizing framework that drives organizational purpose and activities. Diverse projects and programs provide a centralized function that promulgates a systems view of knowledge, whereas stove-piped disciplines and activities can transcend boundaries to enable greater discovery. Portfolio management leverages cross-disciplinary knowledge to increase competitive advantage and achieve optimal results. Outcomes and organizational expectations can also be tested against project realities at ground level and can be communicated and quickly adjusted to mitigate errors and achieve better decision-making.

Problem-centric Approach: Problems should be seen as another outcome of project and program processes, as well as positive, forward-leaning solutions in the form of lessons learned and leading practices. Emphasis on a non-partisan, non-biased, non-judgmental, and pragmatic orientation towards problems and solutions keeps the focus on achievement, improvement, and agile innovation. Organizational expectations are kept pragmatic and constructive when when aligned with problem-centric approaches. At the end of the day, it is about problems, communications, power, and building communities of support focused on credible solutions to challenges. This orientation serves as the thrust for both change and innovation while also addressing competing agendas, administrative barriers, and issues of bias and heuristics, which, when not addressed, could introduce error in decisions.

Governance: Business, administrative, and operations management provides for pragmatic alignment, oversight, approvals, and implementation of project and program operations and establishes rigor and opportunities. In an era of low-cost innovation, management of the budget and clarity of funding requirements that supports the overall effort must be visible and valued by the leadership and the workforce. Nothing invites trouble faster than mismanagement of funds and a lack of focus on funding flow; therefore, the oversight, tracking, and execution of project activities need definition. Defined governance addresses the issue of fragmented implementation and increases executive awareness, as well as formalizing successful and localized grassroots efforts. Senior leadership and advisory bodies understand the cost of KS is a bargain compared to the cost of lost knowledge or not learning lessons.

Knowledge: The essential element for the creation of successful physical and virtual products, services, and processes is knowledge. It can be viewed as an organized set of content, context, skills, and capabilities gained through critical experience, as well as through formal and informal learning that organizations and practitioners apply to make sense of new and existing data and information. It can also be shared as previously analyzed and formatted lessons, practices, cases, and stories that have been captured and applied to new situations. The ascendance of leaders validates the realities of projects and programs to which knowledge can be applied and can be the basis of good decision-making.

All of these imperatives reinforce other imperatives, allowing for various broader objectives of KS to improve and innovate in terms of products and services, thus supporting the efforts and outcomes of projects and programs.

Ed Hoffman is NASA’s Chief Knowledge Officer.

Jon Boyle is NASA’s Senior Knowledge Sharing Consultant.