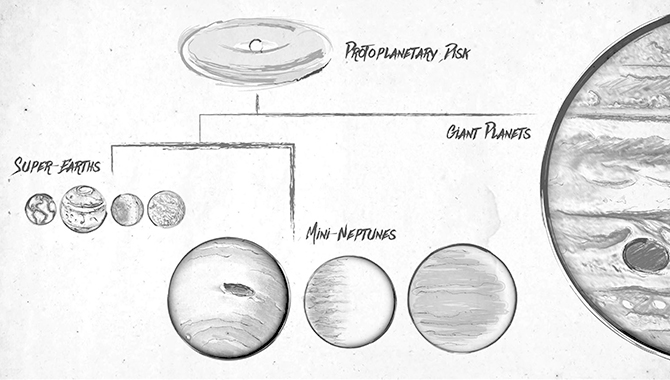

Research based on the final Kepler catalog indicates that smaller exoplanets fall primarily into two categories: super-Earths and mini-Neptunes. Protoplanetary disks, which are born out of swirling disks of gas and dust, give rise to these smaller planets as well as to giant planets similar to Jupiter.

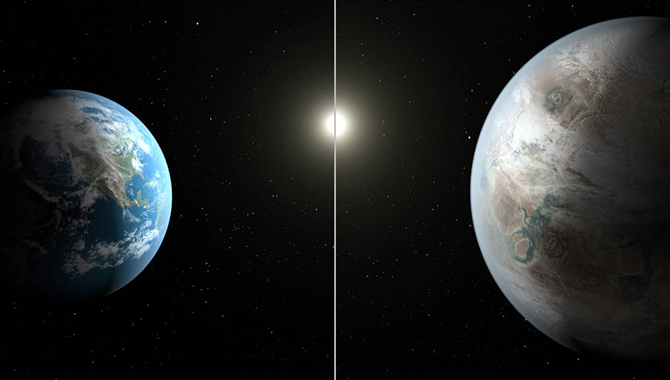

Credit: NASA/Ames Research Center/JPL-Caltech/Tim Pyle

NASA’s Kepler team has released the final catalog of findings from the space telescope’s original mission to seek out Earth-like planets in the galaxy.

Over the course of its four-year mission, Kepler continually observed a single star field located in the Cygnus constellation. The observatory spied more than 4,000 potential planets—some the size of Earth, others as big as Jupiter—of which more than half have been confirmed as exoplanets. Fifty of the planet candidates are terrestrial sized and in the habitable zone of their stars. Planets in this zone—also called the Goldilocks zone—are typically less than twice the size of Earth, presumed to be rocky, and orbit their star at a distance that implies liquid water could exist on the planet’s surface.

The latest catalog based on Kepler data identified hundreds of new potential planets. “[T]here are 219 planet candidates, of which 10 are possibly rocky and in the habitable zone of their star,” said Mario Perez, NASA Kepler program scientist in the Science Mission Directorate (SMD), at a presentation of the new findings.

The closest Earth-analogue identified in the new catalog is KOI-7711. “[I]t receives just about the same amount of energy as we do from our sun, and it’s only slightly larger than the earth at 1.3 Earth radii,” said Susan Thompson, Kepler research scientist at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California.

She cautioned that not enough is known yet about KOI-7711 to determine whether it is truly a twin of Earth. “We need to know more about its atmosphere, whether there’s water on the planet. I always like to remind people that it looks like there are three planets in our habitable zone: Venus, Earth, and Mars. And I only really want to live on one of them.”

Over the years, scientists have scrutinized the data returned by Kepler to identify potential planets. With each new survey catalog, the techniques for identifying and confirming exoplanets in the Kepler data have improved. For the final catalog, Thompson and her team searched the 200,000 stars observed by Kepler for signs of planet candidates, finding a total of 4,034. In addition to carefully vetting the data, they measured the likely undercount of the survey to confirm the completeness of the catalog as well as the predicted overcount to ascertain the catalog’s reliability.

“This latest version of the Kepler catalog was found in a uniform way using sophisticated robo-vetting tools, which means it can be used for statistical analyses to answer questions like ‘How common is the earth in the galaxy?’ and ‘How many solar systems are like ours?’” said Courtney Dressing, NASA Sagan Fellow at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena.

In a separate study based on the new catalog, researchers focused on characterizing the planets to better identify those that might harbor life. Previously, among exoplanets that ranged between one and four times the size of Earth, it was hard to assess which were gaseous and which were terrestrial. The new study found that rocky planets are generally no more than 75% bigger than Earth and possess little to no atmospheres. After that, the exoplanets jump in size to being closer to that of Neptune. These planets typically have thick atmospheres with little to no solid surface.

“This is a new division in the family tree of exoplanets. It’s somewhat analogous to the discovery that mammals and lizards are separate branches on the tree of life,” said Benjamin Fulton, doctoral candidate at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and Caltech, who led the study.

Planets in between the two sizes, with radii of 1.5 to 2 times that of Earth’s, are rare. The reason for the gap is simple: hydrogen.

“Adding a tiny amount of hydrogen to one of these rocky planets—say about 2% by mass—would cause the planet to jump the gap and move into the group of larger planets. Planets need to have a very finely tuned amount of hydrogen and helium to live right in the middle of that gap: between about 0.1% and 1% of hydrogen and helium. And that just doesn’t leave much wiggle room,” said Fulton.

In addition to so-called “super-Earths” and “mini-Neptunes,” Kepler has identified many other exoplanet types: Hot Jupiters, which are as large as Jupiter but as close to their stars as Mercury is to the sun; Cold Gas Giants, which are similar to Jupiter in our solar system; Ocean Worlds and Ice Giants, which are the “mini-Neptunes”; Rocky Planets, which are the “super-Earths”; and Lava Worlds, which are so close to their stars that their surfaces are covered in molten lava.

While the final catalog of Kepler exoplanets is now complete, its second mission, K2, continues the hunt for exoplanets. NASA has several new planet-hunting missions on the horizon as well. Launching in 2018, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) will use the same method as Kepler to detect planets around nearby bright stars. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will then focus on characterizing the atmospheres of exoplanets. In the mid-2020s, the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST) will set out to further characterize exoplanet populations.

Kepler mission development was managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). The Kepler and K2 missions are run by Ames Research Center (ARC) for NASA’s SMD. The spacecraft’s flight system is operated by Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corporation in conjunction with the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

Watch a video about Kepler and the latest survey catalog.

Read an APPEL News article about the Kepler mission.

Explore the candidate and confirmed exoplanets discovered by the Kepler and K2 missions.