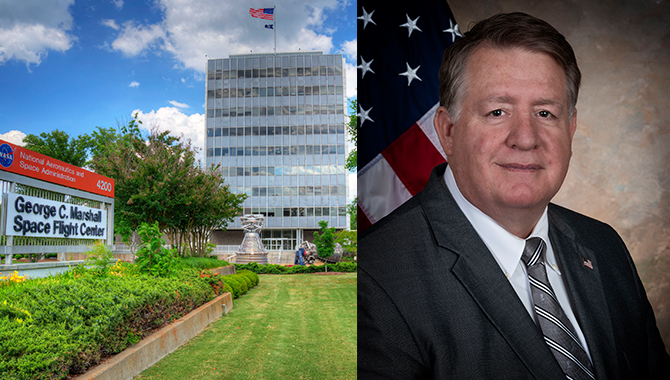

Marshall Space Flight Center CKO Preston Jones.

Credit: NASA

Preston Jones discusses knowledge sharing at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center.

Disclaimer: This material is being kept online for historical purposes. Though accurate at the time of publication, it is no longer being updated. The page may contain outdated information or broken links. Current Knowledge Community Corner articles are available here.

Preston Jones serves as the Chief Knowledge Officer (CKO) at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. Jones is the Associate Center Director, Technical, and provides expert technical assistance and advice to the Center Director, supporting the full spectrum of NASA engineering, science and technology work at Marshall. Working closely with senior managers across the center, he performs special studies, advises and assists in policy reviews and develops benchmarking strategies, ensuring Marshall’s work is technically sound and achieves the goals and requirements of NASA and the nation.

Jones previously served as Director of Marshall’s Engineering Directorate. He began his NASA career in 1982 as an Engineer in Marshall’s Structural Dynamics Laboratory, served as the Liquid Engine Systems Branch Chief in Marshall’s Propulsion Laboratory from 1994 to 1997 and the Propulsion Test Division Chief from 1997 to 2000, and then moved to the Shuttle Main Engine Project Office where he served as the Engine Systems Team Lead.

What are your thoughts on how knowledge sharing affects mission success?

When you achieve mission success, in my view at least, that is the actual demonstration of knowledge sharing. Because of the way we work in this agency no one person or one organization really has all the knowledge to achieve the type of missions NASA undertakes. Just about everything we do is collaborative, meaning that part of the knowledge of some system or process for achieving the mission may reside in industry or academia, or internally across multiple centers.

When you look at our ability to share that knowledge, cross those boundaries, integrate it on launch day, and then execute the mission — whether it’s a science mission, a human exploration mission or a technology demonstrator — I think in every case mission success requires that knowledge be given and received across a wide community. It’s rare that we have stand-alone, sort of, islands of knowledge that do something cradle-to-grave and achieve a mission. Sharing and collaborations may be local to the mission or nationwide or possibly international — crossing continents, politics and cultures.

Even if it’s a scientist that’s working on a payload experiment for the International Space Station or a special instrument or CubeSat that’s been developed by a university intending to ride on the Space Launch System, they still have to interface with the vehicle that’s carrying them, and the ground prep and operations crews. They may have to interface directly with the astronauts to perform specific experiments — if it’s Station, for example. They have to engage and interface and share knowledge across all the different specialties that it takes to execute the science.

How do you think NASA’s technical workforce benefits from knowledge sharing?

I like to think about it as not only sharing, but as capture. The benefit, obviously, is that it allows you to start building on knowledge that has already been captured previously. As you keep growing that and you refine it, it speeds up your work and accelerates your learning relative to various systems. All of that as it applies to a technical workforce makes you more responsive and makes your turnaround times for design and analysis quicker, at least in the engineering world.

But not only that, whether it’s a business process, a procurement process or anything that has been achieved in some other place that’s similar, knowledge can be shared and that’s a benefit. If the Air Force does a procurement and they can do it twice as fast as NASA does it, and we talk to the Air Force and reduce our procurement time, we’ve benefited. We can work collaboratively with the aero industry, for example, on turbine blade design. If they’ve done something in commercial airlines that helps us over on rocket turbines, then that’s a benefit. We’ve had a lot of success in using knowledge that we’ve gained in the past to not only reduce the amount of work we’ve done, but to accelerate the delivery time.

Do you have a favorite story or example of successful knowledge sharing?

One that’s fairly recent is we collaborate and work closely with the Commercial Crew companies that are in the process of building our commercial launch vehicles. We have found that to be a very beneficial knowledge sharing environment where both the prime contractors in that system have shared with us the things they do. And we believe that has increased our understanding of their systems and is part of why we have more confidence in them. They have also learned from us about the added criticalities in design for flying humans and the deeper understanding it takes to qualify and certify systems for human spaceflight. We share with them our previous experiences, previous failures and all the work that we had put into refining and developing certain designs and the reason we develop lessons learned. Commercial Crew is a place where we have learned it is in our mutual benefit to share knowledge fairly openly, and that has been a good test and the story is continuing to get better.

Recently, we had an excellent case with Orion, where Johnson Space Center was wanting to transport Orion on a Super Guppy, and they were having some environment problems with the actual structure in the Super Guppy that was inducing some vibration modes. And because of some work we had done at Marshall on some previous programs using damper systems, we were able to go down and assess and help them better understand the problem. I think in the end, we didn’t necessarily resolve it, but we helped to add to that knowledge base that helped JSC reach a solution to their problem.

Another place I see that we do that quite a bit is when we have failures in the agency, or even outside of the agency. NASA gets called in, and we bring our experts in, and they’re able to share knowledge. One example is the National Transportation Safety Board. We have a number of experts here at MSFC and across NASA that are world-class experts in some very specific areas. So, if the NTSB or DOD or industry needs some of those people, they reach out. We support them with the knowledge that we’ve gained here over the years over a scope of areas, such as material fatigue forensics, valves functions, propulsion, and many different types of detailed analysis capabilities.

Is there a specific project or set of lessons learned that influences your approach to solving problems?

Well, for me personally, I would say most of the problem-solving formats that I’ve learned over the years have been from my early years working Shuttle. One of the processes we use in engineering, for example, is when we have a test incident, or when we have a failure, we go back to the fault tree process. And we work through fault trees that help us understand and question, ‘Just how much knowledge do we really have on all these things and how they interact?’ So, for me, if there was a program that helped influence how I think about problem-solving, how knowledge comes into that, it would have been the Shuttle program.

I see that we still employ those methods a lot today. It’s really not a unique process to Shuttle but was very effective for that program and can be used in a lot of failure or anomaly cases. It’s a format by which you start writing down and understanding what all you know about the system in every case, and then questioning what you really know. The fault tree process forces you to start providing evidence to verify that your existing knowledge is what you thought it was. As you provide that evidence, you start working through a smaller and smaller cause-and-effect scenario, narrowing down the possibilities where you can work to a resolution or smaller set of resolutions.

What are some of the most prominent knowledge challenges in your organization?

Our most prominent challenges are how to capture and transfer and make available knowledge, and how to do it in a properly controlled environment in a world where pieces of knowledge are everywhere and in various forms of accuracy. Knowledge volume is orders of magnitude more than it used to be and increases substantially every day with modern media. Not only how do you capture it and preserve it, but as important is how do you efficiently retrieve it and get precisely the knowledge that you need?

I think it used to be that knowledge management meant, ‘Well, how do I capture that? Because I’ve got this workforce that’s aging and they’re leaving. At least in NASA, “How do I transfer that and how do I maintain it?” has been the driving concern. What I see emerging now is not only how do you capture it and sustain it, which is still a challenging issue. But equally concerning is how do you search, sort and protect the massive amounts of digital data that is now being produced with paperless and digital design tools. How do you data mine it so that what you’re getting is meaningful and it doesn’t take up your whole day, right? Knowledge needs to be efficient in its availability, somewhat timely. We are getting better at that, but we still have much to do as our daily production of information still outpaces our ability to collect and archive it.

I don’t think it’s unique to NASA, by the way, as I see knowledge management issues in industry and all over — we have not yet figured out how to really share and capture our knowledge and preserve it, particularly in cases when the knowledge is held across corporate or agency boundaries. One example that illustrated this was as we were doing the early definition trades for SLS and looking back at the Apollo/Saturn V rocket. Even with as much archival as was done on that program, there were still areas of the design intricacies that no longer exist. We found that as voluminous as the Saturn records are, there probably isn’t enough to go straight to manufacturing if we chose to just recreate the design. Obviously, you wouldn’t manufacture the same way. And I don’t know that being able to recreate it was particularly needed, but it did highlight that we have always had knowledge-saving gaps, even when we were trying harder than we do today — like on Apollo. I do know that as time marches on toward paperless archival of every email, every design or every analysis iteration, it makes the difficulty of understanding what key configurations or integrated systems are becoming just as challenging to sort and filter through the overwhelming information. It’s an interesting challenge. I see the agency beginning to step up to try to do some of that stuff, but it’s not funded at the level that I think is going to be needed to really capture a lot of the great activities that are going on here within the agency, with agency partners and outside with other agencies.

What’s the biggest misunderstanding that you think people have about knowledge?

I think the big misunderstanding about knowledge is that you — we — think you’ve got it. I mean, I think the biggest misunderstanding is, when you think you have knowledge, do you really have knowledge? Then, what’s the validity of it? Because I think most of the times when we have failures, we would step back from it after the failure and we would say, ‘Well, we didn’t have knowledge that we all thought we had, or else we wouldn’t have had a failure.’

I think the biggest misunderstanding about knowledge is that we think we have more knowledge than we maybe really do have. Sometimes we must extrapolate between the knowledge gaps with engineering judgment, which all engineers definitely need. It’s the nature of delivering designs in the real-world balancing of risk, cost and schedule. When we get it right and our judgment works, we continue forward. This confirms our judgment application so to speak, but it also informs our approach the next time we have to make a judgment call. However, when we get it wrong and have a failure then we are forced to face our knowledge is not what we thought it was and our response is, of course, to go get more data, go get more knowledge — test, reanalyze, redesign, etc.

One memory I have of how our confidence can misguide us around our actual knowledge is a sign that hung on the wall after we had the Challenger failure. The Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Motor Office had a big sign on every wall in the hall. It had a big red circle that said ‘NO HUBRIS’ with a line through it. That’s kind of what I’m saying here. It’s saying, ‘Hey, when you’re confident enough that you believe you know all the knowledge, then we all should be aware of our collective thinking and why it is the rationale we believe. Prior to Challenger, a NO HUBRIS sign was not on any wall. In this human exploration business we are in, doing difficult, challenging endeavors, the hardware usually teaches us things — many understood, and some misunderstood. It resets our understanding of what we really know. So, the big misunderstanding about knowledge, at least in my view, is the understanding that what you think you know can lead you to believe that you are done. At some point things must go forward. Progress has to be made. But don’t fool yourself that you or your team knows all there is to know because problems can occur though conditions the best human minds can’t anticipate or conceive. If we could, we’d fix them.

Are you observing any trends or cultural shifts that affect knowledge management going forward?

I think the cultural shift I see is you have a generation of young people that are entering the workforce that for the time they’ve been on Earth, they’ve had a computer in their hand. They’re much more virtual in their ability to react and interact with coworkers and access knowledge and employ it. There are great things about that and there are bad things about that, but it’s just a cultural shift I see. I think that in its extreme, if it’s taken to where you’ve got one guy sitting next door to another person and they are emailing him or her for the answer when one of them could walk over, then I think you’ve kind of defeated the purpose. Or maybe that is the purpose for some. But it is bothersome that we don’t seem to have the face-to-face interactions we used to have.

One example of what I am talking about with respect to cultural change within NASA that really still bothers me quite a bit is I don’t see the travel level from center to center or the agency technical forums to be nearly as prevalent as they used to be. Travel still occurs, particularly within the program and project offices, but it’s less often and much more difficult now for engineering organizations to do center-to-center dialogs, tours, or share and really know each other’s capabilities and develop those interagency networks. We tend to do all of that digitally now and through electronic media. It’s fast. It’s efficient. But what lacks there is the knowledge relationship that you have with another person, especially among the early to mid-level engineering folks.

Who are the biggest users of the knowledge services in your organization?

I think at Marshall our biggest users of knowledge services are our Engineering Directorate and, to some extent, our Science Directorate. We have a number of scientists here that are also very, very deep into scientific research, whether it’s heliophysics, astrophysics or terrestrial surface science. As far as engineering goes, our engineering is engaged in everything from observatories to space launch vehicles, and everything in between, whether it’s a water or air system for station or whether it’s a habitat or Gateway. All of those things require various skills and knowledge, so the biggest user of that at this center is the Engineering Directorate, which holds most of our chief engineers and our technical expertise.

There is quite a bit of knowledge that goes along with that at the center, which is the program/project management knowledge. We pride ourselves on being a center of integration and design for large, complex systems such as SLS, Human Landing System, Hubble, Chandra, ISS nodes, etc. For example, with SLS we are integrating the complete vehicle stack along with Orion and the service module and any payload that would be put on that rocket. We are going to be doing that integration and coordination across the various NASA centers and with the Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate.