Gemini VII as seen from Gemini VI-A during the more than five hours of maneuvering the astronauts performed during the first spacecraft rendezvous. The two spacecraft are approximately 43 feet apart at this point, eventually closing to about one foot apart.

Credit: NASA

Borman, Lovell set record for space endurance and rendezvous with Gemini VI-A.

Among astronauts in the U.S. space program in 1965, Gemini VII wasn’t considered a pilot’s mission. The flight plan called for two astronauts to share the small Gemini capsule—about the size of the front seats of a car—for 14 days, performing a series of experiments primarily to answer questions about human endurance in space. The mission would be twice as long as any human had spent in space to that point, setting a record that would stand for five years.

Donald K. “Deke” Slayton, then the assistant director of NASA Flight Crew Operations, tapped Frank F. Borman II to serve as Command Pilot. Borman joined NASA in 1962 as an accomplished fighter pilot. He respected Slayton’s integrity in a difficult job and had never discussed crew assignments with him.

Astronauts Frank Borman (right), command pilot, and James A. Lovell Jr., pilot, are the prime crew members for NASA’s Gemini-Titan 7 (GT-7) mission.

Credit: NASA

“I figured when they gave me Gemini VII, we’d do the best we could with it,” Borman recalled in an oral history. “And fortunately, I didn’t have a choice in [Pilot James A.] Lovell [Jr.] either, but it turns out that was wonderful. Jim Lovell was a wonderful guy to spend 14 days with in a very small place.”

Borman did balk, however, at a proposal by medical personnel to simulate the mission on Earth first, with he and Lovell sitting in a similarly confined space 24 hours a day for 14 days.

“And I, you know, ‘They’re out of their mind. Fourteen days sitting in a straight-up ejection seat on Earth? You’re crazy!’ We were able to get that nonsense kicked out in a hurry. And then we just went about our business, doing the best we could,” Borman recalled.

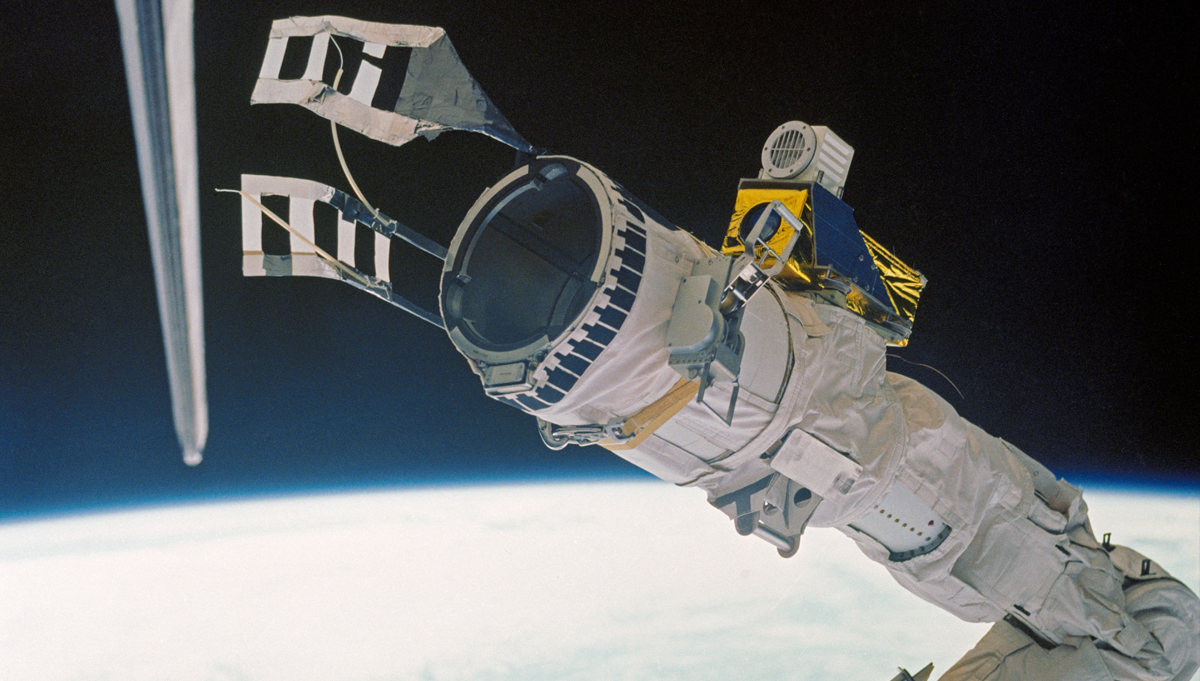

However, by the time Gemini VII launched on the afternoon of December 4, 1965—55 years ago this month—it had become much more of a pilot’s mission thanks to an explosion in October. Gemini VI had been scheduled to launch on October 25 and practice the crucial docking maneuvers that were key to the success of Apollo. But their target, an upper rocket stage with a docking port known as an Agena Target Vehicle, exploded nearing orbit. Command Pilot Walter M. Schirra, Jr. and Pilot Thomas P. Stafford were already in their capsule waiting to follow the Agena into space. The launch was quickly scrubbed.

In the urgency to beat the Soviet Union to the Moon, NASA developed a revised mission, Gemini VI-A, that would launch on December 15 and rendezvous with Gemini VII on day 11 of that mission. It would be the first time NASA had two crewed spacecrafts in orbit simultaneously, the first time four humans were in space at the same time, and the first rendezvous in space. “I was all for it. I thought it was great. And this is another example of the flexibility in management that made NASA so successful,” Borman recalled.

The first 10 days of Gemini VII were spent performing experiments, testing new spacesuits, and working in a new “shirtsleeves” environment without wearing space suits. When Lovell and Borman first caught a glimpse of Gemini VI-A through the capsule window, they initially mistook it for a star.

“…We were tired, and the systems on the spacecraft were failing. We were running out of fuel, and it was a real high point to see this bright light (it looked like a star) came up, and then eventually we could see it was a Gemini vehicle,” Borman recalled.

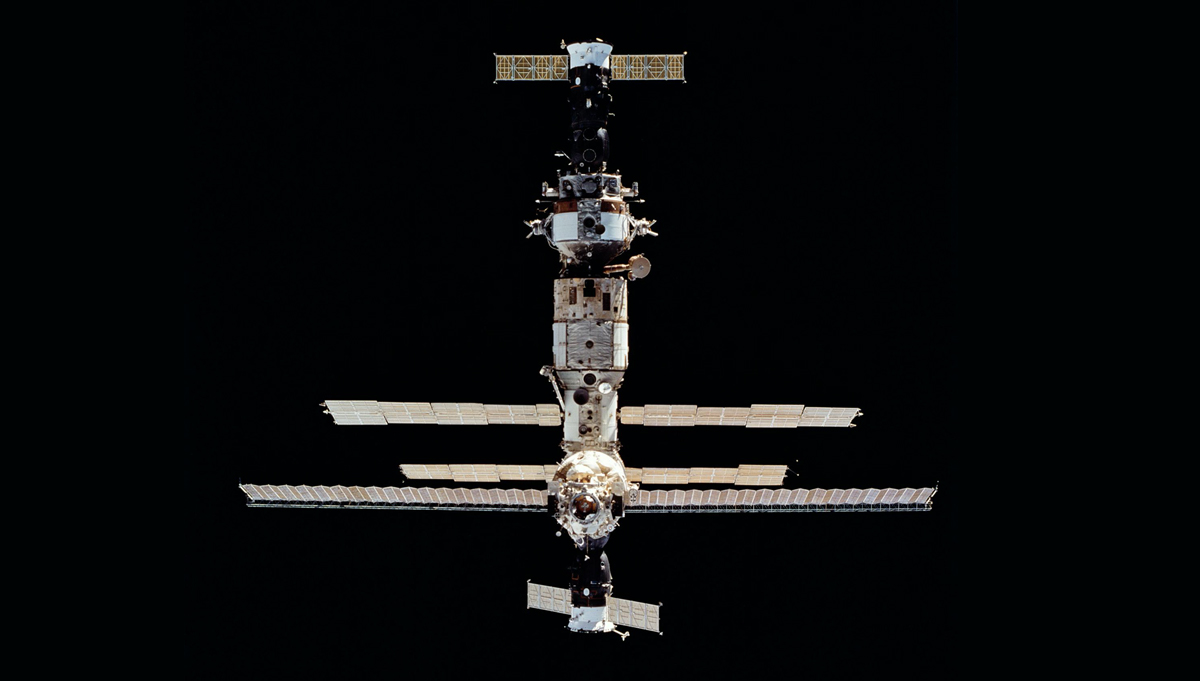

Gemini 6A closes to within 35 feet of its sister capsule, Gemini 7, on Dec. 15, 1965. Credit: NASA/JSC/ASU

The two spacecrafts rendezvoused at 2:33 p.m. on December 15, eventually coming within one foot of each other. All four of the astronauts took turns at the controls, guiding the capsules on intricate maneuvers around each other for more than five hours. Because the spacecrafts were not equipped with compatible docking ports, the astronauts chose to align the capsule windows instead.

At one point, Schirra, who was a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy along with Lovell and Stafford, held up a sign in the capsule window that read, “Beat Army,” referencing a 7-7 tie in the annual Army-Navy Game that year. Borman, a no-nonsense graduate of the U.S. Army’s United States Military Academy at West Point had the last laugh.

“Frank Borman topped me, though, darn it, if you’ll remember that,” Schirra recalled in an oral history. “He said, ‘Look at that sign. It says, “Beat Navy.” The heck it does!”

“Wally was always one to inject some levity into the program,” Borman recalled. “And, God bless him, he really did a good job in everything he did. He just has a different—he has that little quirk of being able to include some fun with things. I never had that.”

Gemini VI-A returned to Earth on December 16, splashing down in the North Atlantic Ocean, with recovery by the crew of the U.S.S. Wasp. Two days later, on December 18, the crew of the Wasp recovered Gemini VII. The mission added a great deal to scientific understanding about human performance over what was then an extended period of time in what is still an exceptionally confined space. Although in one respect, perhaps the capsule was just a little too big.

“… I don’t know how in the world we could, but in that small area, somehow, that small volume, we lost a toothbrush. We ended up sharing a toothbrush!” Borman recalled with a laugh.