Taken aboard Apollo 8 by William A. Anders, this iconic picture shows Earth rising above the lunar surface as the first crewed spacecraft orbited the Moon.

Credit: NASA

One billion people were following news of the first spacecraft to reach the Moon with humans aboard.

When Apollo 8 launched 50 years ago this month, on December 21, 1968, it was estimated that nearly one-third of the world’s population—1 billion people—was actively following news of the mission. The spacecraft was the first ever bound for the Moon with humans aboard and it would forever change human perspective.

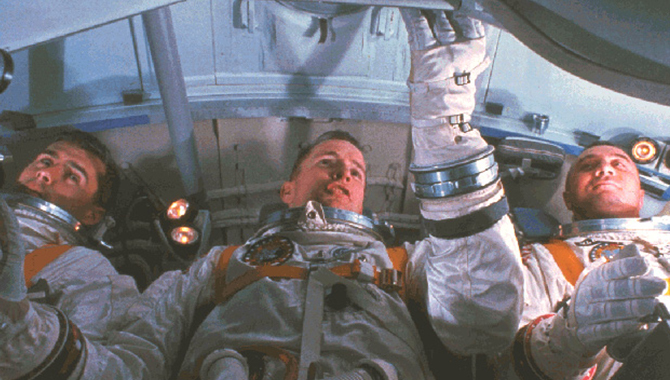

13 Nov. 1968–These three astronauts are the prime crew of the Apollo 8 lunar orbit mission. Left to right, are James A. Lovell Jr., command module pilot; William A. Anders, lunar module pilot; and Frank Borman, commander. They are standing beside the Apollo Mission Simulator at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC).

Credit: NASA

NASA veteran Frank Borman was the flight’s Commander; James A. Lovell Jr. was the Command Module Pilot, and William A. Anders was the Lunar Module Pilot, although there was no Lunar Module on the flight, because of development delays. Lovell was originally a backup for Michael Collins, who was bumped from the mission as he recovered from surgery for a bone spur in his neck.

“…I never expected to be on Apollo 8. But I have to tell you, that was the high point of my space career,” recalled Lovell, in an oral history.

Apollo 8 launched from Kennedy Space Center atop the Saturn V, a 363-ft-tall rocket that weighed 6.2 million pounds and created a remarkable 7.6 million pounds of thrust at launch. Fifty years later, it remains the tallest, most powerful rocket ever launched.

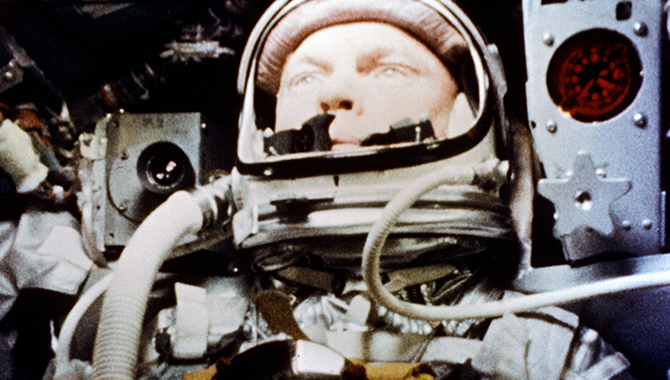

“The Saturn V was a unique vehicle. And of course, it was powerful and noisy and vibrated, and the stagings were really kind of violent. But when you got on the third stage, the S-IVB, it was smooth and quiet and was just like the upper stage of the Gemini. Actually, it was less demanding than Gemini from a g standpoint, because it didn’t reach the high-g’s,” said Borman, in an oral history.

The crew was focused on delivering a successful mission, coming on the heels of the achievement of the Apollo 7 crew, and knowing they were setting the stage for an eventual landing on the Moon in a later mission. Borman recalled rejecting an attempt to add an Extravehicular Activity [spacewalk] to the mission en route to the Moon.

“… I just wouldn’t buy that. The main objective was to go to the Moon, do enough orbits so that they could do the tracking, be the pathfinders for Apollo 11, and get … home. Why complicate it with a bunch of other stuff?” Borman recalled.

The spacecraft reached 24,208 mph, the fastest speed reached by humans at that time. It took Apollo 8 68 hours to travel the approximately 240,000 miles to the Moon, beginning the first of 10 orbits on December 24. The crew had a full slate of tasks during the 20 hours they were in lunar orbit, tracking landmarks and potential landing sites, photographing the Moon’s surface, and performing sextant navigation.

21-27 Dec. 1968–This Apollo 8 view of the lunar surface looks southward at 162 degrees west longitude, showing rugged terrain that is characteristic of the lunar farside hemisphere.

Credit: NASA

“We were so curious, so excited about being at the Moon that we were like three schoolkids looking into a candy store window, watching those ancient old craters go by from—and we were only 60 miles above the surface,” Lovell recalled. “…To be there was such an exciting moment… I felt very, very honored and lucky to be there.”

The mission included several live television broadcasts, including one on Christmas Eve as the astronauts orbited less than 70 miles above the surface of the Moon. 1968 had been a year of high-profile assassinations, riots and war. The astronauts famously concluded the broadcast by reading the first 10 verses from the King James Bible, concluding with “And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas—and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth.”

Borman said that “looking back at the Earth on Christmas Eve had a great effect … for me. Because of the wonderment of it and the fact that the Earth looked so lonely in the universe. It’s the only thing with color. All of our emotions were focused back there with our families as well. So that was the most emotional part of the flight for me.”

Seeing this new perspective had a great effect on the American people, as well. It not only proved the concepts of a Moon landing but bolstered the national mood and garnered stronger support for the space program. The astronauts received a telegram, upon their return to Earth, that read, “Thank you for saving 1968.”

“You know, with riots and assassinations and the war going on, I was part of a thing that finally gave an uplift to the American people about doing something positive… That’s why I say Apollo 8 was really the high point of my space career,” Lovell recalled. The crew would collectively be named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year.”

The mission is also remembered for the iconic image of the Earth rising over the surface of the Moon, captured by Anders and used on a popular postage stamp for years to come. Apollo 8 left Moon orbit on December 25 and splashed down in the Pacific Ocean two days later. Lovell, who had originally been slated for Apollo 11 before being moved to Apollo 8, became the commander of Apollo 13. During that crisis, he used a procedure from his Apollo 8 training—one that was absent from the Apollo 13 flight manuals—to save that mission.

“I think Apollo 8 was a very important mission,” Borman recalled. “But, you know, you also have to say: It wasn’t just Apollo 8 that was an important mission, because 8 couldn’t have happened without 7. If … Wally and his crew hadn’t done a perfect job, we couldn’t have gone on 8. And 11 couldn’t have happened unless 9 and 10 were perfect. It was a well-thought-out plan; and Apollo itself couldn’t have happened unless Gemini had done the job; so I think that every one of these flights was very, very important.”

29 Dec. 1968–Although it was past 2 a.m., a crew of more than 2,000 people were on hand at Ellington Air Force Base to welcome the members of the Apollo 8 crew back home. Astronauts Frank Borman, James A. Lovell Jr., and William A. Anders had just flown to Houston from the pacific recovery area by way of Hawaii. The three crewmen of the historic Apollo 8 lunar orbit mission are standing at the microphones in center of picture.

Credit: NASA