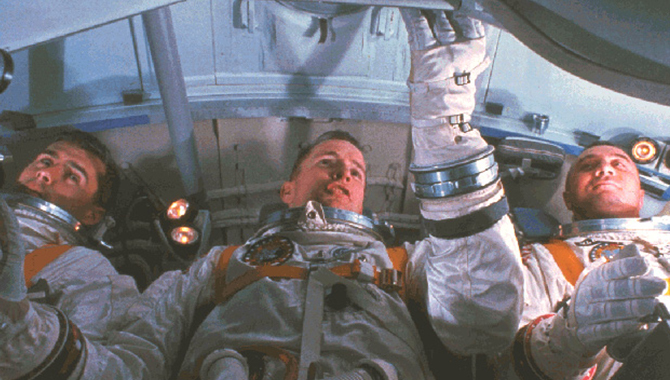

Astronauts for the first Apollo mission (L-R) Roger B. Chaffee, Edward H. White and Virgil I. Grissom practice for the mission in the Apollo Mission Simulator.

Credit: NASA

A deadly fire during a routine test shocked the nation and lead to a solemn vow to be tough and competent.

One of the worst days in the history of the U.S. space program began as a routine test. The “plugs out” simulation on January 27, 1967 was to measure how the Apollo Block I space capsule, due to launch in less than a month, would perform under its own battery power. Because there was no fuel in the capsule or the massive Saturn IB rocket beneath it, the test wasn’t designated as hazardous.

Then, at 6:31 p.m., five and a half hours after the three astronauts entered the command module, one of them, believed to be Command Pilot Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom, urgently reported a fire. The blaze swept through the capsule in a matter of seconds, fed by the combination of about 70 pounds of flammable material, such as nylon netting and Velcro fasteners, and an atmosphere of pure oxygen.

When rescue crews removed the hatch several minutes later, three of NASA’s top astronauts were dead.

“Apollo 1 came as a real shock. … To lose a crew in a ground test—I mean, they’re still sitting there on the ground—to lose a crew really woke everybody up,” said Astronaut Alan Shepard, in an oral history collected by C-SPAN in 1998.

“We were part of a group that had gone through Mercury, had gone through Gemini,” said Shepard, noting that this long string of successes had created a sense in some that “you know, nothing can go wrong. It led to a sense of false security, no question about it.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson allowed NASA to conduct a thorough investigation into the fire at the request of NASA Administrator James E. Webb. The U.S. Senate and House of Representatives also conducted investigations. The mission was known as Apollo 204 or AS 204 at the time. It was later designated Apollo 1 at the request of the astronauts’ widows.

After extensively photographing the command module and practicing disassembly techniques on a duplicate example, NASA investigators took the command module and subsystems apart, looking for the source of the fire. Although that source was never conclusively determined, investigators identified the most probable initiator as an electrical arc near the environmental control system instrumentation power wiring. This corresponds to a series of electrical anomalies recorded several seconds before astronauts reported the fire.

The fire burned exceptionally fast and hot—exceeding 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit in a matter of seconds—largely because the capsule was filled with pure oxygen at 16.7 psi. This launch environment, which was also used in the Mercury and Gemini programs, was selected to protect astronauts from decompression sickness (the bends) in the event of a rapid depressurization of the capsule, as well as because a dual gas system would have been heavier.

The Apollo 1 capsule door was a complex, three-part design, with the innermost piece opening inward, requiring depressurization to operate. The process of opening the door took at least 90 seconds, whereas the fire had consumed all the oxygen within the capsule in about 25 seconds. Additionally, in the early seconds of the fire, pressure increased rapidly until it ruptured the capsule. In those conditions, it would have been impossible to open the door.

The ground crew fought valiantly to extinguish the fire and open the exterior portion of the capsule door, driven back again and again by thick, acrid smoke billowing from the rupture. Firefighters arrived nearly nine minutes after the first report of the fire. They weren’t at the launchpad because the test wasn’t designated as hazardous.

The U.S. Senate investigation determined that “no single person bears all of the responsibility for the Apollo 204 accident. It happened because many people made the mistake of failing to recognize a hazardous situation.”

Specifically, the report by the Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences singles out the false sense of security Shepard mentioned, noting, “The committee can find no other explanation for the failure of the hundreds of highly-trained people on the Apollo program, including the astronauts, to evaluate the conditions under which the test was being conducted as hazardous.”

The tribute at the Apollo/Saturn V Center at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center opened Jan. 27, 2017, 50 years after the crew was lost. It features numerous items recalling the lives of the three astronauts. It also includes the three-part hatch to the spacecraft itself, the first time any part of the Apollo 1 spacecraft has been displayed publicly.

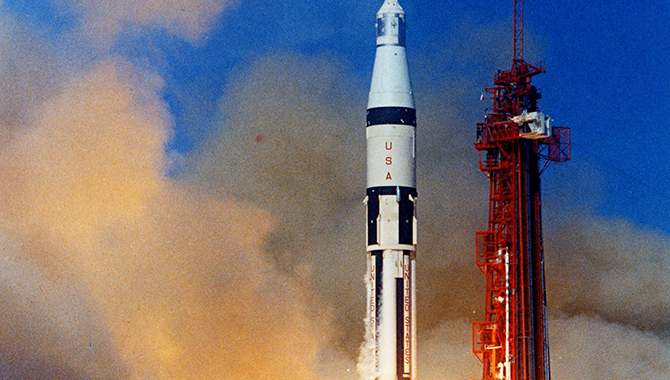

Credit: NASA

The tragedy shocked the nation. Grissom, as one of the original seven astronauts and a veteran of the Mercury and Gemini programs, was a national celebrity. Senior Pilot Ed White was the first American to walk in space during an EVA in the Gemini 4 mission. Pilot Roger B. Chaffee was a promising newcomer who worked in Mission Control during Gemini 3 and 4.

The tragedy hit NASA hard, as well. Although astronauts were largely drawn from the ranks of the nation’s top pilots and understood the risks of space travel, losing friends to a fire on the ground was a shock. This was compounded by the fact that Grissom and others had voiced dissatisfaction with the command module’s development before the test. In the aftermath, the agency redoubled its commitment to the Apollo program while going through the grim task of examining the command module for clues. The investigation led to an extensive redesign of the command module, the discontinuation of a 100 percent oxygen environment on launch, and development of a new, outward opening hatch door with exploding bolts.

The costly lessons of Apollo 1 changed the agency. On the Monday following the Friday evening fire, Flight Director Gene Kranz called a meeting of his branch and flight control team and issued what became known as “The Kranz Dictum,” which charted a course for Apollo’s later successes.

“…We were too gung-ho about the schedule and we locked out all of the problems we saw each day in our work … Not one of us stood up and said, ‘Dammit, stop!’ … From this day forward, Flight Control will be known by two words: Tough and Competent. Tough means we are forever accountable for what we do or what we fail to do. We will never again compromise our responsibilities… Competent means we will never take anything for granted… Mission Control will be perfect. When you leave this meeting today you will go to your office and the first thing you will do there is to write Tough and Competent on your blackboards. It will never be erased. Each day when you enter the room, these words will remind you of the price paid by Grissom, White, and Chaffee. These words are the price of admission to the ranks of Mission Control.”

Looking back, Shepard said, “I don’t think there’s any question about the fact that the Apollo 1 fire did shape up the whole system, did make people realize that they had been too complacent, that they were overconfident, and it resulted, of course, in a total redesign of many of the parts of the spacecraft. And I’m sure contributed to what was a very highly successful [program].”